Many health policy experts believe that direct-to-consumer (DTC) advertising by pharmaceutical companies misinforms gullible consumers, encourages drug overconsumption, increases health care costs, strains doctor-patient relationships and undermines the quality of patient care. For example:

- The American College of Physicians and the American Society of Internal Medicine (ACP-ASIM) in a joint policy statement wrote, “We are concerned that advertising will result in increased consumption of these [highly advertised] drugs; though their use may be neither appropriate nor necessary.”1 The organizations also wrote, “Many times, physicians will give in to the demand and when they don’t, often patients will ‘doctor shop’ until they find a physician who will prescribe the medication.”2

- Sen. Tim Johnson (D-S.D.) also questioned the growth of DTC. “Is the information value worth the yearly increases in drug costs that advertising inevitably causes? Are patients getting the best individual choices of medicines or just the best-advertised ones? Are generic drugs, often an excellent cost-effective alternative, getting equal consideration?”3

- Dr. Phillip Alper of the University of California at San Francisco, responding to an article in the Journal of the American Medical Association (JAMA) by Alan F. Holmer, president of the Pharmaceutical Research and Manufacturers of America (PhRMA), wrote, “Holmer plays down the inflationary effect of DTC advertising, with which the costliest drugs are pitched with all the skill that the advertising budgets of pharmaceutical companies can buy.…Nor does Holmer discuss the effect on physicians who become involuntary appendages of manufacturers’ public relations departments as they field questions inspired by print and television drug ads.”4

- Dr. David Kessler, while commissioner of the federal Food and Drug Administration (FDA), responding to a 1992 study that found 57 percent of 109 pharmaceutical advertisements had little or no educational value, said, “ It heightens awareness of the degree to which misleading information may pervade the ‘informational marketplace.’”5

- Finally, members of the Committee on Bioethical Issues of the Medical Society of the State of New York wrote, “Direct drug advertising provides no real benefit to patients, is potentially harmful, and is costly. We therefore urge the U.S. Food and Drug Administration to review and strengthen its policies concerning this practice.”6

Are these criticisms accurate? In some cases, yes. For example, DTC advertising does encourage more drug consumption — which can lower some health care costs when drug therapy precludes the need for other, more expensive therapies.7

However, the above-mentioned concerns largely are misdirected. They focus on the evolving pharmaceutical marketplace when in fact the whole health care system is in transition. And direct-to-consumer pharmaceutical ads are a response to the transitional process, not the cause of it.

The U.S. health care system has reached a crossroad, and the direction the country takes will determine the type, availability and quality of care for years to come. Pharmaceutical advertising presupposes that health care consumers can make choices for themselves — and that’s the type of health care system people want. Those who have no choice in health care have no need of advertising.

A Health Care System in Transition

The U.S. health care system is in transition from a physician-directed system to a patient-directed one. The apparent problem is that patients, physicians, insurers — all of us — must endure the temporary inefficiencies that result from that transition.8

A greater potential problem is that politicians, seeing the turmoil and patient dissatisfaction that arise during the transition, will try to step in and save us from the changes. They could legislate inefficiencies that would plague us for years to come.9

The Changing Role of Information in the Health Care System

America is in the forefront of the Information Economy. One of the hallmarks of this new economy is access to much more information by many more people. The U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics recently reported that worker productivity is up by 2.2 percent.10 A primary reason is that as workers we have much quicker access to the information we need to do our jobs.

In an extension of this principle, patients have much greater access to health care information, especially through the Internet and through advertising. 11 Indeed, the most important change occurring in the health care system is this access to information. According to health care consultant Lyn Siegel:12

- About 25 percent of online information is related to health;

- More than 50 percent of adults who go on the Web use it for health care information; and

- More than 26 percent of people who go to disease-oriented Web sites ask their doctors for a specific brand of medication.

Thus information is driving the transition to a patient-directed health care system.

The Informed Physician

A generation ago physicians were the possessors of all medical information. Patients went to physicians and accepted evaluations and diagnoses almost without question. Patients who want second opinions and physicians who gracefully accede to their wishes are relatively new phenomena.

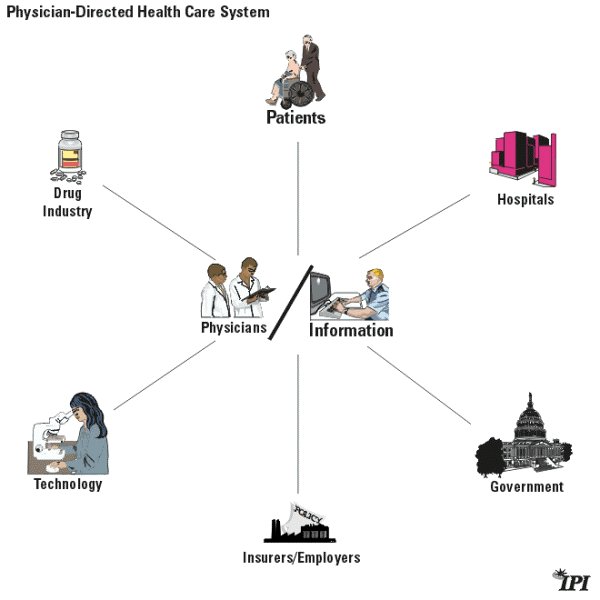

Figure 1 depicts a physician-directed health care system in which:

- Physicians have all the extant medical knowledge and skills.

- Physicians perform all patient examinations.

- Patients accept their physicians’ diagnoses and insurers pay for the care.

- Hospitals admit patients based on physicians’ orders and pharmacists fill the prescriptions.

- Drug and medical device companies market to the physicians who control all access to patients.

In this model, no one reaches patients without physicians’ consent.

Why the Physician-Directed System Is Disappearing

The physician-directed health care system worked well for several decades. The vast majority of working Americans had good health insurance benefits that protected them, their families and their assets from catastrophic losses due to a major accident or illness.13 Third-party payers were generous in their reimbursement policies while doctors and hospitals could do only so much. Whatever doctors recommended, insurers covered.

Once the amazing medical advances of the 1970s and 1980s began to appear, health care costs began to soar. Insured workers and seniors on Medicare were insulated from the cost of care, and so had little incentive to control health care spending. Employers and the government, who paid most health care bills, desperately sought cost-control mechanisms. That’s when managed care came in. Its proponents claimed that managed care could lower the cost of comprehensive health care coverage, in part by controlling utilization. While the arguments continue over how well managed care controlled costs and whether it sacrificed quality to achieve savings, the growth in health care spending did slow during the 1990s. Recently, though, the rate of growth has escalated and engendered fears of more double-digit increases in health care spending.

Meanwhile, the expansion of managed care helped to undermine the physician-directed health care system. Insurers and employers gained the power to question and even override doctors’ decisions, which put doctors in an uncomfortable and unsatisfactory position.14

Patients also reacted negatively. Many believed their doctors were willing or able to give them only the level of care their insurers would cover. This distrust undermined the doctor-patient relationship and spurred patients to seek health care information directly, rather than from their doctor or insurer. Thus health care consumers began to exploit the Information Economy. They would have done so eventually anyway, but their concerns over managed care accelerated the change.

Figure 1

The Rise of a Patient-Directed Health Care System

Increasingly, patients are entering the health care system armed with information — and sometimes misinformation. They may not know how to practice medicine, but many know something about their medical condition and the options available to them. And they raise questions if the doctor follows a different path than the one they expect. As Dr. Thomas R. Reardon, past president of the American Medical Association, has insightlfully noted:

Patients themselves are also creating a strong impetus for change. Disillusioned by restrictions on coverage and care, they are increasingly demanding choice of physician, hospital, and even type of health plan. More than ever, patients see physicians as the essential point of trust in a changing system, and demand choice and stability in their vital relationships with their doctors.…At the same time, patients themselves are becoming better educated, not only about insurance options but also about medical treatments. Today, thanks to the Internet, trends in product advertising, and the massive proliferation of medical information, patients are better equipped to take part in their care than ever before. Rather than simplifying the physician’s job, however, this increased patient knowledge base is creating new challenges.15

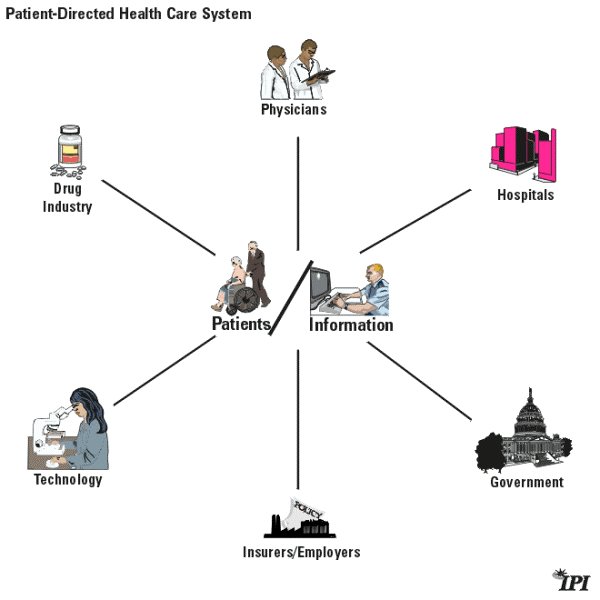

As Figure 2 lays out, we are transitioning toward a patient-directed health care system — if the federal state governments don’t intervene — in which all of the components cater to the patient, rather than the physician. It is impossible to overstate the magnitude of the change. We aren’t there yet, but the system is moving — or being pulled — in that direction.

Figure 2

In the new system, insurers and employers, doctors and other health care providers, researchers and pharmaceutical companies will view the patient rather than the provider as the primary consumer. And in the new system:

- Insurers will have to create products that consumers rather than their employers want.

- Doctors will have to please their patients rather than insurers, reinvigorating the weakened doctor-patient relationship.

- Pharmaceutical and medical device companies increasingly will market directly to the consumers who use their products.

Because health care consumers are becoming better informed, they will, on balance, make better decisions. And they will want even more information. But how do companies and providers reach individuals with the information the latter want and need? One way is through advertising.

Advertising Provides Information People Want

Every Sunday newspaper is filled with advertising flyers for department stores, office products, computers, cars, food and clothing. Yet people don’t complain they can’t afford food because all the grocery stores advertise. And does anyone really think they would be able to get a computer for less money if none of the computer manufacturers and retail outlets advertised?

In virtually every sector of the economy, those with products or services to sell must get information to those who will buy. Advertising is the vehicle for getting information to the intended customers. It tells prospective customers about product availability, quality and cost — the information those prospects need in order to make comparisons. While some people may consider it annoying if they are not looking for a particular product, those in the market for the advertised item often will pay close attention to ads and other marketing techniques such as direct mail and communication from sales representatives.

Of course, companies do not have to advertise. Some rely on reputation or location to attract customers. Ironically, companies that eschew advertising often sell their products at higher prices than companies that advertise heavily.

Does Advertising Raise Costs?

The general assumption is that advertising raises the costs of products. This assumption recently has entered the debate over the impact of drug companies’ advertisements aimed at consumers.16 But advertising can — and should — lower costs. For example, according to economist John Calfee of the American Enterprise Institute:

A pioneering study compared the prices of eyeglasses in states that either permitted or restricted advertising for eyeglass services. Prices were about 25 percent higher where advertising was restricted or banned (and prices were highest for the least educated consumers). A later study by the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) staff showed that product quality in the states without advertising was not higher despite the higher prices. Studies also found higher prices in the absence of advertising for such diverse products as gasoline, prescription drugs and legal services.17

How is it that advertising can actually lower costs? Most products have certain fixed costs, plus some variable costs. While variable costs are imputed to each item produced, fixed costs are divided by the number of products sold. The goal of advertising is to expand consumer awareness and increase sales. The more items sold, the greater the economies of scale and the lower the fixed costs per consumer.

Holman Jenkins of the Wall Street Journal explains the rationale:

The media also complain about advertising as if this were an extra cost borne by drug users. Drug companies spend on advertising because it’s profitable — it pays for itself by generating additional sales, allowing development costs to be spread over a larger number of users. The average price to each user is lower.18

In the absence of competition, advertising might raise prices. But in the absence of competition, vendors would likely raise prices whether they advertised or not. Competition keeps manufacturers from charging as much as they would like, except in cases where there is an unusually high demand for a particular product (as when everyone decides they want a Cabbage Patch doll, a Tickle Me Elmo or a Furby for Christmas). Thus even when advertising doesn’ ;t increase sales, vendors cannot add the cost on top of the product if there are other competitively priced alternatives on the market.19

The Growth of Pharmaceutical Advertising

For years pharmaceutical companies have devoted most of their marketing budgets to advertising their products in professional journals, sending sales personnel to visit doctors and provide samples that doctors then passed on to their patients — all of which is known as “professional spending.” These efforts went, and still go, largely unnoticed by the media and population in general.20 Thus relatively little criticism focuses on how much drug companies spend on marketing to doctors and hospitals. And those critical of DTC spending seem to assume that professional spending should continue without interference.

How Much Do Drug Companies Spend on Marketing?

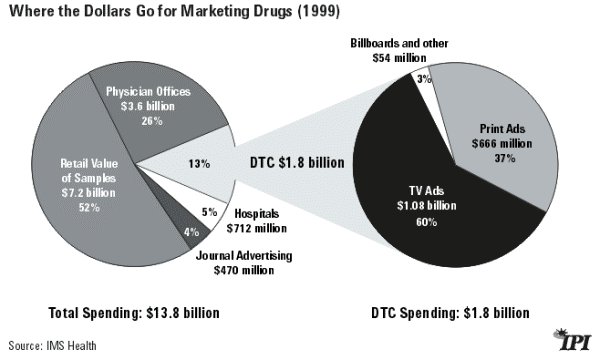

Direct-to-consumer ads are often blamed for driving up the cost of prescription drugs. But as Figure 3 shows, in 1999 drug companies spent only 13 percent ($1.8 billion) of their marketing dollars on direct-to-consumer efforts and 87 percent ($12 billion) on professional spending. The largest share of the money (albeit the retail value rather than the actual cost of production) goes to handing out samples to physicians, which are in turn handed out to patients.

Figure 3

Does Drug Advertising Drive Up Drug Costs?

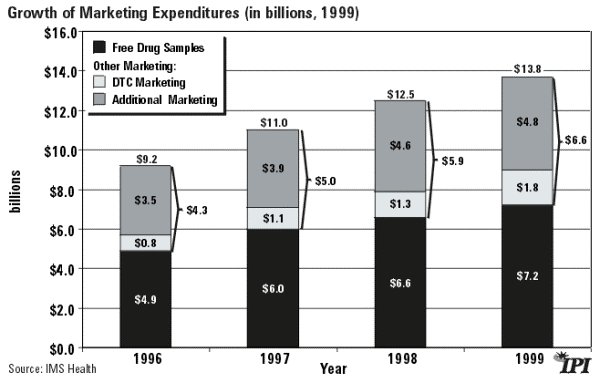

If marketing expenditures were actually driving up the cost of drugs, you would expect to see a significant increase in total marketing spending since 1997 when the FDA relaxed DTC ad rules — corresponding to what critics claim are the rising costs of prescription drugs. However, as Figure 4 demonstrates, total marketing expenditures have grown at a fairly steady rate.

Indeed, the rate of increase declined each year from 1996 to 1999 (e.g., the increase of 18 percent between 1996 and 1997 fell to 11 percent between 1998 and 1999). Moreover, the volume of free samples, which makes up more than half of the marketing budget, grew by more than 45 percent over that period.

Figure 4

However, while total marketing expenditures may be increasing at a relatively constant pace, the allocation of dollars within the marketing budget is changing . As health care shifts from a physician-directed to a patient-directed system, pharmaceutical companies are changing their marketing focus from doctors to patients — at least with respect to those drugs that have a broad-based appeal. In less than a decade, DTC advertising has increased from $55 million (1991) to $1.8 billion (1999).21

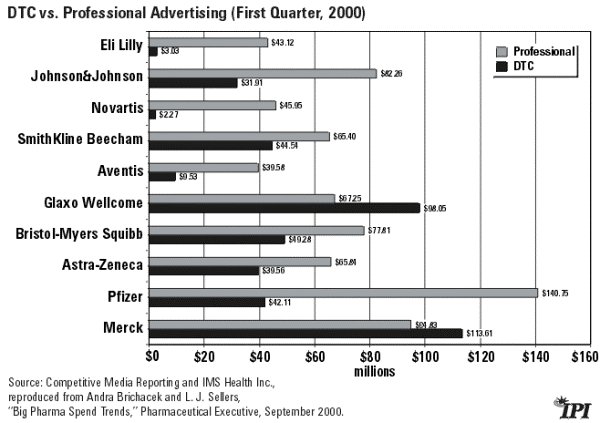

As Figure 5 shows, most of the “Big Ten” pharmaceutical companies spent significantly more money on professional marketing in the first quarter of 2000 than on DTC. However, both Merck and Glaxo Wellcome (now GlaxoSmithKline) spent more on DTC. Such a change would have been unimaginable just a few years ago. But a further shift to a patient-directed health care system likely will cause other companies to rethink their advertising mix as well.

Figure 5

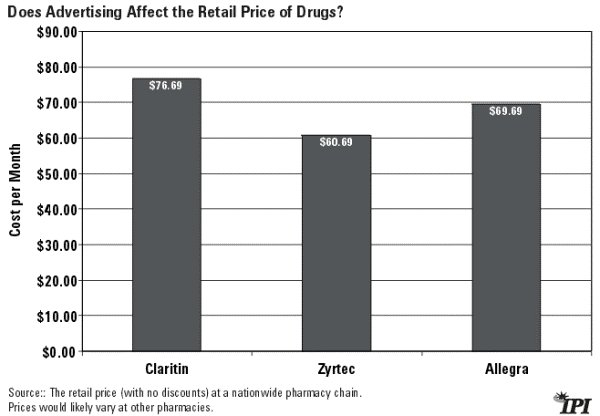

But doesn’t the increase in DTC advertising drive up the cost of the advertised drugs? Not in any discernable way. Let’s look at the three leading prescription oral antihistamines: Claritin, Zyrtec and Allegra. The amount spent advertising these drugs varied widely. Schering-Plough spent $137.1 million in 1999 promoting Claritin to consumers, while Pfizer spent less than half that amount promoting Zyrtec ($57.1 million) and Aventis spent about a third as much on Allegra ($42.8 million).22

As Figure 6 shows, Claritin is a little more expensive than the other two, but its ingredients may account for the price difference. Claritin is non-sedating while Zyrtec is. The ability to work, drive or operate machinery while taking an oral antihistamine would easily be worth an extra $16 a month to many employees. Allegra is only $7 a month less than Claritin, which spends about three times as much on DTC advertising. If there were a direct correlation between advertising expenditures and price, you would expect Claritin to be significantly higher than the other two in order to recapture advertising expenses. That’s not the case.

Figure 6

Of course, not all prescription drugs are suitable for DTC advertising. Drug companies probably will spend little or no DTC money to reach patients with cancer or lupus because their numbers are relatively small and their doctors’ role in deciding the best course of therapy is great. Drugs targeting such medical conditions as AIDS may see limited DTC spending. For example, Glaxo Wellcome spent only $2 million in 1999 advertising its HIV antiviral drug Combivir, while Du Pont spent only $721,000 on its antiviral drug Sustiva.23 The primary marketing target for these and several other diseases will remain the physician. However, pharmaceutical treatments for diseases that have widespread populations such as allergies, high blood pressure and pain increasingly will be marketed direct to consumers.

The Impact of DTC Advertising

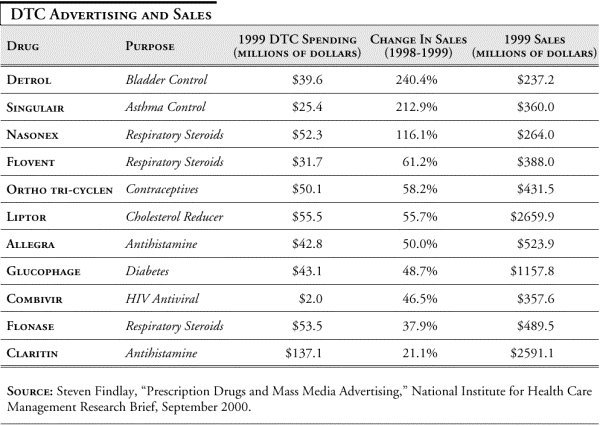

Direct-to-consumer ads apparently have affected consumer behavior by increasing drug sales. But as with all advertising, the dollars spent on advertising produce widely varying results. Table 1 outlines some of this disparity.

Table 1

- $39.6 million was spent promoting Detrol directly to consumers, while there was a 240 percent increase in sales. That expenditure represented about 16 percent of sales.

- $137.1 million was spent on Claritin with only a 21 percent increase, but that still meant an additional $450 million in sales. However, because of diminishing marginal returns, Schering-Plough recently decided to cut back advertising on the drug.

- Only $2 million went into DTC advertising for Combivir, yet the drug experienced a 46.5 percent increase (about $114 million) in sales.

While there may be a tendency to assume that DTC expenditures led to the increased sales outlined in Table 1, the wide variations indicate that sales increases are a result of many factors, such as doctors’ deciding that one drug is better than its competitors. While advertisers might like to think their ads can produce a 240 percent increase in sales, as occurred with Detrol, there simply is no direct correlation between advertising expenditures and sales for most drugs.

The Role of Competition

Even if it is true that advertising lowers prices for most sectors of the economy, isn’t the market for prescription drugs different? In a real market:

- Companies create products they think will sell and advertise to attract customers and maximize sales. That is beginning to happen in the pharmaceutical industry, as companies increasingly advertise to consumers.

- When a company is successful in attracting customers to its new products, profits may go up — which in turn attracts competitors offering the same or a similar product. When a company has the corner on a market, often because of a copyright or patent, economists call it “monopoly profits.” Competitors may then try to develop knock-offs or substitutes that will attract some of those consumer dollars.

- Once competition begins, companies look for ways to maintain market share. They may cut prices, advertise more or engage in other activities to attract more consumers.

- If competitors are successful, the sales of the first company will begin to decline and its profits also may fall.

Economists know this pattern well and usually favor letting the process work. The lure of profits is what drives companies to come up with new products and drives other companies to imitate successful products. Thus new ideas or products may earn the creators a great deal of money for a short time, but monopoly profits often will decline when competitors move in.

While increased advertising expands information and enhances brand recognition, it doesn’t necessarily increase competition. If there is only one product treating a specific illness or medical condition, the manufacturer can still make monopoly profits. However, manufacturers have to be more cautious about pricing when there are competing brands, and many medical conditions are now treatable with various products.

Competition among Prescription Drugs

The drug industry is very competitive. No drug company has more than 5 to 6 percent of the worldwide pharmaceutical market.24 And changes in the health care system and in patients’ access to information are making the market even more competitive.

Of course, critics argue that drug patents, which prohibit generic drug manufacturers from selling an identical product for much lower prices, limit competition. This is true in the sense that a soft drink manufacturer cannot copy the ingredients of Coca-Cola and market the resulting product as “ Close-a-Cola.” But competition in the soft drink industry is fierce.

Similarly, among the top 50 prescription drugs advertised DTC in 1999:25

- Three (Claritin, Zyrtec and Allegra) were oral antihistamines for allergies.

- Four (Flonase, Nasonex, Flovent and Nasacort) were inhaled respiratory steroids.

- Three (Glucophage, Rezulin and Avandia) were oral diabetes medications.

- Two (Xenical and Meridia) were antiobesity drugs.

- Two (Zomig and Imitrex) helped migraine headaches.

- Three (Premarin, Cenestin and CombiPatch) were for menopause.

- Three (Celebrex, Vioxx and Enbrel) were antiarthritic drugs.

The existence of two or more drugs to treat a medical problem means there is competition among drug manufacturers, and that’s the essential ingredient necessary to keep prices down.

Case Study: Pain Medicines

Pharmaceutical research and development have led different companies to create different patentable products for the same condition. For example, in January 1999, Pharmacia subsidiary Searle released its new “COX-2” inhibitor, Celebrex, followed a few months later by Merck’s Vioxx. These COX-2 inhibitors, termed “superaspirins,” are as effective as other non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) if not more so, and they block the COX-2 enzyme that is believed to cause gastrointestinal problems some patients suffer when taking other NSAIDs.

The release of these two drugs caused an enormous market shift in the traditional NSAID market. By December 1999, out of 49 million U.S. prescriptions written for arthritis, 29 percent were for the COX-2 inhibitors. 26

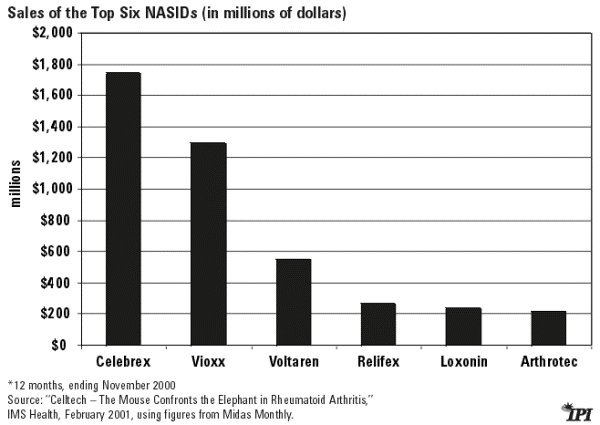

Since 1999 the market has shifted even more dramatically. Figure 7 shows total sales for the six major NSAIDs (12 months, ending November 2000).27

- Sales of Vioxx about equaled sales of the four non-COX-2 inhibitors combined, while Celebrex sold about a third more than all the non-COX-2 inhibitors combined.

- Celebrex and Vioxx together captured about 70 percent of the NSAID market.

Having so many products targeting chronic pain creates a real “churn” in market share. By the end of 1999, Celebrex, which had been on the market about a year, had sales of $1.3 billion, while Voltaren, which had been on top of the market a year earlier, had only $614 million in sales. Near the end of 2000, Celebrex had experienced even more sales growth ($1.749 billion) and Voltaren more decline ($553 million).

Figure 7

But this is only part of the story. Three COX-2 inhibitors currently are in Phase III trials and could be FDA-approved in the next few years, and at least seven more are in earlier stages of research.28 It is possible that some of these newer drugs will be serious competitors of Celebrex and Vioxx within a few years, creating even more churn in the market.

Will Competition Lead to Lower Prices?

Critics claim that drug companies sell their products for much more than it cost to produce them. This is true, but it is hardly unusual. How much does it cost to “burn” a copy of a new CD for which consumers will pay $18 at the music store? Reproduction is so cheap that America Online gives its CDs away.

The difference between the actual reproduction costs and the price of a CD goes to pay the retailer, the artists and the producers, and some portion is invested in future ventures. That is precisely what happens with prescription drugs. Pharmaceutical companies turn today’s profits into tomorrow’s new, lifesaving drugs.

Like any business, drug companies try to maximize profits. Competition forces them to keep prices lower than they otherwise would. For example, the superaspirins discussed above cost about the same amount retail — around $75 to $85 a month. That’s not a coincidence. Drug companies’ efforts to determine the appropriate price for a new drug’s release, or “ launch” price, take into consideration a number of factors including what the competitors charge.29 Sales of both Celebrex and Vioxx have been remarkably high, indicating a strong demand for a pain reliever with minimal gastrointestinal side effects. Absent competition, prices might have been even higher. And the fact that 10 competitors are in the production pipeline means that prices likely will fall as makers of the new drugs launch them at lower prices to gain market share — or the makers of the two primary products lower their prices to retain market share.

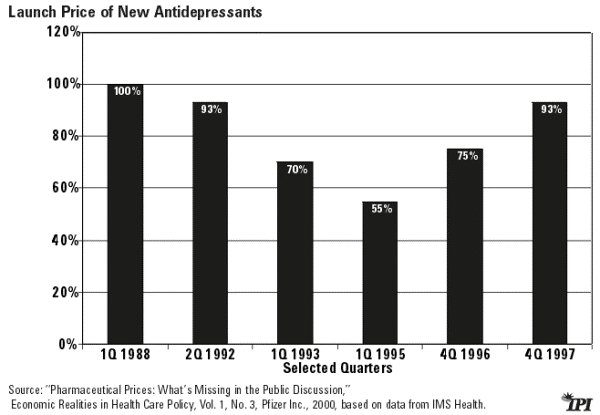

Figure 8 shows the release dates (by quarter) of several antidepressants, beginning with the first in 1988. All of the subsequent antidepressants were launched at a lower price than the original drug, indicating an attempt to gain market share.

Figure 8

“ Mature markets,” like the market for antidepressants and antihypertensives in which several new products compete with aggressive generic brands, can be even more volatile and still remain profitable.30

Growing competition among drugs is forcing drug makers to be price conscious. Large institutional purchasers such as HMOs and pharmacy benefits managers (PBMs) consider efficacy and price, or what people usually mean by the word “value.” Pricing a drug too high relative to its benefits and suitable alternatives means it will be passed over for the competitors.

Most physicians also try to include value in their prescribing decisions and will recommend a less-expensive drug if they expect the outcome to be the same.

Currently, however, price competition at the retail level for individual purchasers is minimal, and for an important reason: health insurance insulates most consumers from the cost of prescription drugs. As a result, most drug consumers are not price conscious. This renders the retail prescription drug market less competitive than it could be. Fortunately, even this situation is changing. Increasingly, patients are buying prescription drugs online where they often get discounted prices, and that change may pressure pharmacies to lower prices. Remember: manufacturers are not the sole determiners of product prices; retail outlets also play an important role. Yet there has been almost no discussion at the national level of whether or to what extent pharmacies could lower prices.

In addition, the reforms discussed below can alter consumers’ perspectives and allow the prescription drug market to work more like a normal market.

DTC Advertising as an Emerging Market

As the nation moves toward a patient-directed health care system, consumers will want even more information about available drugs. DTC will be a key source of that information. While almost all health policy analysts recognize that fact, many don’t like it. They are calling for FDA review of DTC advertising in the hope that the government will set new and more restrictive guidelines for DTC ads.31 This is a mistake.

Prior to the 1997 reforms, the FDA imposed a number of restrictions on DTC ads that made them confusing and ineffective. Drug manufacturers could mention the name of their product or a disease in a commercial, but not both without including a long list of possible negative side effects — a list too long for a TV commercial. Thus, the audience might hear the name of a drug but have no idea what it was for. Such commercials were only confusing, not informative. Having the government step in again likely will take us backward, not forward.

That does not rule out improvements in the young prescription-drug ad industry. Advertisers may not yet know how to provide good, useful information in the most efficient manner. Beth Miller, senior vice president and director of CME Health, a marketing firm, has discussed a survey conducted by her firm of consumer attitudes toward DTC prescription drug ads. According to Miller, “ ;The results proved what we suspected. The vast majority of consumers don’ t like, or don’t care about, much of the category’s creative executions [i.e., the way the message is delivered].” 32 Eighteen of the top brand names were included. She concludes: “On average, the advertising scored only 33 percent aided awareness, although several brands exceeded 60 percent awareness levels. But while the study found pharmaceutical marketers can generate awareness, the hurdle most have to clear is developing advertising [that] people actually like and [that] can influence their behavior, ultimately leading to prescription and purchase.”33 Since likability is the strongest factor in predicting sales, according to Miller, DTC marketing clearly needs to learn how to deliver its message most effectively.

Without government intervention, direct-to-consumer advertising will be the engine behind more information and competition — and eventually lower prices. Will these DTC ads be promotional? Of course. But as economist John Calfee has pointed out, the public approaches such ads with a healthy level of skepticism and still takes away a great deal of information.34

DTC Advertising and Competition

As the market for prescription drugs becomes ever more competitive, the nature of the advertising will change. The first stage in advertising is to create brand awareness, as prescription drug companies are doing now. Soon, consumers will want to know more than the name and what a drug is supposed to do; they will want to know why one drug is better than another. Eventually, they will want to know what the product costs and why it is a better value than its competitors.

Virtually none of the drug companies compete on price in their ads. But that too likely will change. For example, when ophthalmologists started advertising refractive eye surgery for myopia (near-sightedness), they provided information only about the benefits of the service. Soon they began to discuss the skills and experience (quality) of the doctor who would be doing the procedure. Today, many ads boldly proclaim the price of the eye surgery as well as the doctor’s skill and experience. And the price of the surgery is gradually declining.

Will DTC ads for prescription drugs follow the same path? Probably, at least to some extent. As mentioned earlier, so long as patients are insulated from the cost of a product, quality is much more important than value (the relationship between cost and quality). But price may begin to play some role if the makers of, say, Vioxx and Celebrex think it will make their product more attractive to potential consumers.

What Do Consumers Think of Pharmaceutical Advertising?

Consumers appear to like the fact that pharmaceutical companies are reaching out directly to them. And surveys indicate they make use of that information. The FDA’s Center for Drug Evaluation and Research conducted a survey in August of 2000 to investigate who had encountered DTC prescription drug ads and how they had affected the consumers’ decisions. According to the survey: 35

- 80 percent said that if they were to see an ad for a drug that treats a condition that was bothering them, they would talk to their doctor about the drug.

- 51 percent who had seen a doctor in the last three months said that a prescription drug ad caused them to look for more information about the drug.

- 54 percent said that advertisements for prescription drugs helped them have better discussions with their doctor about their health.

- And 72 percent rejected the notion that prescription drug advertisements made it seem that a doctor wasn’t needed to decide if a drug was right for them.

Did these respondents find that their physicians reacted negatively when they asked about a prescription drug they had seen advertised? No. According to the survey, only 4 percent of respondents said their physicians got angry or upset.

- 71 percent said the doctor “seemed to react like it was an ordinary part of the visit.”

- 81 percent said the doctor welcomed the question.

- And 79 percent said the doctor discussed the drug with them.

In addition, an often-cited survey conducted by Prevention Magazine found that 80 percent of the respondents said their doctors were “very willing” to discuss advertised drugs and another 15 percent said their doctors were “somewhat willing.”36 Doctors’ skepticism may be fading as more and more patients embrace the new Information Economy.

How Will DTC Advertising Affect the Health Care System?

Putting information in the hands of consumers who didn’t have that information before is a revolutionary business — and revolutions engender change. Critics know this and raise concerns that DTC advertising will increase health care spending, strain doctor-patient relationships and confuse consumers and patients. Worst of all, they believe going directly to the consumer is only a drug company technique to increase prices and therefore profits. Are any of these concerns valid?

Will DTC Advertising Increase Health Care Spending?

Probably, but that is not necessarily bad. Increased health care spending is only bad when it is wasteful and inefficient. For example, if doctors were to prescribe medicines for patients who had no medical need, that would be wasteful — and unethical. However, very few doctors would prescribe medicines their patients do not need. In fact, a new Prevention Magazine survey found that about half of those who talk to a doctor as a result of a DTC ad receive no drug therapy.37

A greater concern is that patients, having seen an expensive brand-name drug advertised, will want it rather than a generic equivalent. When patients or their doctors choose brand names over generics, their choices may increase total health care spending. But, again, that may not be bad. The brand name may be higher in quality or slightly different in composition. And it may have fewer side effects. Thus it may offer additional benefits, in which case the additional cost may be justified.

If an expansion of DTC advertising means that we are treating more people who otherwise might have just suffered in pain or endured a debilitating condition, then increased medical spending is positive.

Some have argued that increased drug spending may lower total health care costs if less-expensive drug therapy replaces more-expensive surgery or other procedures. This may be true for individual patients, but it cannot be aggregated to apply to the whole health care system. Total spending will continue to rise because the American health care system will continue to do more and more for patients.

Will DTC Strain the Doctor-Patient Relationship?

Historically, doctors informed and patients performed. That is, doctors diagnosed and issued instructions that patients followed — or at least were supposed to. With more information at the patients’ fingertips, that relationship is changing. Patients are asking questions, and doctors are beginning to see the questions as opportunities to enhance patients’ understanding and sense of responsibility about their own health. (The author himself has asked a physician about an advertised prescription drug, and neither he nor the doctor saw anything unusual or unethical about the exchange.)

Doctors may have to take more time to discuss with their patients why Drug A, which the patient saw advertised on TV, would not in the doctor’s opinion be as good a choice as Drug B. Cost, efficacy and suitability all may play a role in that discussion. Some irascible patients may refuse to accept the doctor’s advice. But this occurs even without DTC advertising. Indeed, current DTC advertising is very subtle. No announcer tells the audience to demand Drug A from a doctor because it has been clinically proven to be better than Drug B. DTC ads tend to convey too little information rather than too much. This may change, but the medical community already is learning to deal with people who come to the doctor not just as patients but as consumers.

Will DTC Ads Confuse Patients and Consumers?

Most opponents of DTC advertising appear quite paternalistic with regard to consumers. They seem to think that the public is easily duped by ads and should therefore be protected from them. However, consumers appear to disagree. According to the FDA survey mentioned previously:38

- 82 percent of consumers reported being aware of a drug ad’s information about the risk of the drug.

- And 81 percent said they heard who should not take the advertised drug.

Economist John Calfee contends that three decades of research on advertising has led to two basic understandings of the consumer-advertisement interaction.

First, advertising has an unsuspected power to improve consumer welfare. As a market-perfecting mechanism, advertising arises spontaneously to attack serious defects in the marketplace. Advertising is an efficient and sometimes irreplaceable mechanism for bringing consumers information that would otherwise languish on the sidelines. Advertising’s promise of more and better information also generates ripple effects in the market. These include enhanced incentives to create new information and develop better products. Theoretical and empirical research has demonstrated what generations of astute observers had known intuitively, that markets with advertising are far superior to markets without advertising.

The second finding is that competitive advertising is fundamentally a self-correcting process. Some people may find this surprising. Well-informed observers once thought that unregulated advertising would bring massive distortion of consumer information and decisions. Careful research, however, has shown these fears to be groundless. Self-correcting competitive forces in advertising generate markets in which information is richer and more fundamentally balanced than can be achieved through detailed controls over advertising and information.39

Is DTC Just a Way to Increase Drug Prices?

Drug companies advertise for the same reason every other company and industry advertises: to increase sales with a view to increasing profits. The consumer benefit is that as competition grows, prices usually fall.

By contrast, in the absence of marketing prices would not go down, but up. Just consider under which scenario a manufacturer is more likely to charge high prices for low quality: where there is no advertising and consumers have no way to comparison-shop without taking their own time to go from store to store to compare price and quality, or where advertising takes that information directly to the consumer?

It is not advertising that increases the price of products, it’s the lack of it. High prices thrive in an atmosphere of ignorance. If critics want to see the price of prescription drugs fall, they should encourage even more advertising and competition.

The Missing Ingredient in the Prescription Drug Market: Value

As long as patients are insulated from the cost of medical care and doctors stand between patients and their prescriptions, the health care marketplace cannot work exactly like a normal market in which consumers demand from vendors quality, service and reasonable prices — that is, value. 40

But the U.S. health care system can take on some of the dynamics of a market, and in fact is already doing so. There is some competition; there is some DTC advertising; and prices at least for some health care products and services are relatively low.

As we continue to move into a patient-directed system, market forces may become more apparent. For example, if most people chose to combine a Medical Savings Account (MSA) for small expenses with a catastrophic health insurance policy for large expenses, patients would pay for their prescription drugs out of the MSA and thus be more cost-conscious.

In addition, the realization is growing in Washington that the current tax subsidy for health insurance causes problems. As a result, Congress may pass a tax credit that will help the uninsured purchase a policy. This in turn may lead to a fundamental shift in the type of health insurance policy people purchase — and facilitate the move to a patient-directed system.

Conclusion

American health care is in transition from a physician-directed to a patient-directed system. Increasingly, patients want to collaborate with physicians to make decisions based on the latest and most accurate information. DTC advertising has a vital and growing role in the provision of this information.

Congress and state legislatures recognize that a transition is underway, but they are not sure how to respond. They have tried to make health insurance more available and affordable, yet its price is once again increasing at double-digit rates and the number of uninsured is higher than ever. Most legislation has only made matters worse. Now some legislators want to regulate not just the quality and safety of prescription drugs, but the way in which manufacturers market those drugs. Such regulation would be a catastrophe.

As the market for prescription drugs becomes more competitive, consumers have more choices of high-quality drugs at reasonable prices. It is competition and DTC advertising — not government regulation — that enables the choices and will enhance the benefits. If legislators and health policy experts want to ensure that more drugs are available at lower prices, they should consider policies that encourage advertising and competition. We have no reason to fear advertising; what we should fear is the people who want to control it.

Endnotes

- “ Direct to Consumer Advertising for Prescription Drugs,” Governmental Affairs and Public Policy, ACP-ASIM Online, October 8, 1998 ( www.acponline.org).

- Ibid.

- Sen. Tim Johnson, “Direct-to-Consumer Advertising and Rising Prescription Drug Prices,” delivered to the Senate, November 1, 2000.

- Phillip R. Alper, “Direct-to-Consumer Advertising: Education or Anathema,” Journal of the American Medical Association, Vol. 282, No. 13, October 6, 1999.

- Quoted in Matthew F. Hollon, “Direct-to-Consumer Marketing of Prescription Drugs: Creating Consumer Demand,” Journal of the American Medical Association, Vol. 281, No. 4, January 27, 1999.

- Committee on Bioethical Issues of the Medical Society of the State of New York, “Direct-to-Consumer Advertising: Education or Anathema.”

- For a discussion, see William A. Haseltine, “Genomics: The Path for Science, Medicine and Society,” Brookings Review, Brookings Institution, Winter 2001.

- See Robert Emmet Moffit, “High Anxiety: Working Families Need Market-Based Health Care Reform,” in Empowering Health Care Consumers through Tax Reform, ed. by Grace-Marie Arnett (Ann Arbor, Mich.: University of Michigan Press, 1999), pp. 35-53.

- For example, the U.S. Congress and virtually every state legislature have considered managed care reform legislation. However, by the time Congress does pass something the president will sign – if it ever does – the managed care market may have evolved so that the legislation is irrelevant. On the impact of state legislatures, see Michael A. Morrisey, “State Health Care Reform: Protecting the Provider,” in American Health Care: Government, Market Processes, and the Public Interest, ed. by Roger D. Feldman (New Brunswick, Conn.: Transaction Books, 2000), pp. 229-66.

- U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, “Productivity and Costs,” press release, March 6, 2001.

- Morton H. Meyerson, “Wiring the Health Revolution,” The 21st Century Health Care Leader, ed. by Roderick W. Gilkey (San Francisco: Jossey-Bass Publishers, 1999), pp. 231-41.

- Lyn Siegel, “DTC Advertising: Bane or Blessing?” Pharmaceutical Executive, October 2000.

- For an overview of the history of health insurance, see Robert B. Helms, “ The Tax Treatment of Health Insurance: Early History and Evidence, 1940-1970,” in Empowering Health Care Consumers through Tax Reform, pp. 1-26.

- Joe Flower, “Forces and Scenarios that Will Shape Health Services Delivery,” The 21st Century Health Care Leader, pp. 31-33.

- Thomas R. Reardon, “Challenges to Physician Leaders,” The 21st Century Health Care Leader, p. 263.

- See, for example, Gardiner Harris, “Drug Firms, Stymied in the Lab, Become Marketing Machines,” Wall Street Journal, July 5, 2000.

- John E. Calfee, Fear of Persuasion: A New Perspective on Advertising and Regulation, Agora Association (Monnaz, Switzerland; distributed by AEI Press, Washington, D.C., 1997), pp. 10-11. See also Lee Benham, “The Effect of Advertising on the Price of Eyeglasses,” Journal of Law and Economics, Vol. 15, 1972, pp. 337-52.

- Holman W. Jenkins Jr., “What the Veep Doesn’t Know about Drug Prices,” Wall Street Journal, July 12, 2000.

- For example, in 2001 the Coca-Cola Company may spend an extra $500 million to advertise internationally to promote its core brands, according to the Wall Street Journal. Because of heavy competition from other soft drink manufacturers, the company cannot just add that expense to the price of a soft drink. Indeed, the company may reduce prices to promote sales. Betsy McKay and Suzanne Veanica, “How a Coke Ad Campaign Fell Flat with Viewers,” Wall Street Journal, March 19, 2001.

- Scott Hensley and Shailagh Murray, “Use of Samples in Drug Industry Raises Concern,” Wall Street Journal, July 16, 2000.

- Michael S. Wilkes, Robert A. Bell and Richard K. Kravitz, “ Direct-to-Consumer Prescription Drug Advertising: Trends, Impact and Implications,” Health Affairs, Vol. 19, No. 2, March/April 2000, p. 112.

- Ibid.

- Steven Findlay, “Prescription Drugs and Mass Media Advertising,” National Institute for Health Care Management Research Brief, September 2000.

- “Improved Market Share through Merger and Acquisition Consolidation,” PricewaterhouseCoopers, 2001.

- Steven Findlay, “Prescription Drugs and Mass Media Advertising.”

- “Potential of the COX-2 Inhibitor Market,” IMS Health, March 30, 2000.

- “Celltech – The Mouse Confronts the Elephant in Rheumatoid Arthritis,” IMS Health, February 2001, using figures from Midas Monthly.

- “COX-2 Inhibitors or Traditional NSAIDs?” IMS Health, March 6, 2001.

- See Terri Bernacchi, “The Challenge of Prescription Drug Pricing,” Pharmaceutical Executive, March 2001.

- See “Antihypertensives Market To Be Worth More than $52 Billion by 2007,” MedAd News, March 27, 2001.

- Chris Adams, “FDA to Review Policy Allowing Drug Ads on TV,” Wall Street Journal, March 2001.

- See the discussion between Beth Miller and Harry Swenney, “Are Current DTC Ads Ineffective? Two Points of View,”Medical Marketing & Media, November 16, 1999.

- Ibid.

- Calfee, Fear of Persuasion, pp. 37-40.

- “Attitudes and Behaviors Associated with Direct-to-Consumer (DTC) Promotion of Prescription Drugs,” Food and Drug Administration, Washington, D.C., August 2000.

- “A National Survey of Consumer Reactions to Direct-to-Consumer Advertising,” Prevention Magazine, 1999.

- Ed Slaughter and Martha Schumacher, “Prevention’s International Survey on Wellness and Consumer Reaction to DTC Advertising of Rx Drugs,” Prevention Magazine, 2000.

- “Attitudes and Behaviors Associated with Direct-to-Consumer (DTC) Promotion of Prescription Drugs.”

- Calfee, Fear of Persuasion, p. 96.

- Of course, a health care system that works exactly like the economy may not be ideal. Americans likely will continue to want health insurance that pays their medical bills and protects them from catastrophic financial loss and medical experts who serve as medical doorkeepers.