Synopsis

Senate filibuster repeal or reform is being considered once again. While the filibuster was not part of the U.S. Constitution, the Senate has long embraced rules that promote extended debate on issues and bills. However, current filibuster rules are increasingly used to stop the legislative process rather than make it more deliberative. Returning to the “talking filibuster” wouldn’t change the 60 votes needed to end debate, but it could expedite the process.

“I guess the gentlemen are in a pretty tall hurry to get me out of here. ... And I’m quite willing to go, sir, when they vote it that way— but before that happens I’ve got a few things I want to say to this body.”

Jimmy Stewart as Jefferson Smith

Mr. Smith Goes to Washington

Had Mr. Jefferson Smith (Jimmy Stewart) gone to Washington after 1975, the much-loved film about his Senate filibuster would have been a lot less interesting—and less physically demanding.

Senate filibuster repeal or reform is back now that Democrats control the U.S. House of Representatives, the Senate and the White House. Many of them are pushing to end the filibuster so they can ram through their political and economic agendas without the need for Republican support.

A few of the more moderate Senate Democrats oppose filibuster repeal. And President Joe Biden says he prefers to not “get rid of” or “make changes to” the filibuster, though he and a few others have signaled they’d consider some changes.

The filibuster has been altered several times over the decades, and we think change today could be beneficial. But any effort to do so should be guided by an understanding of its history and purpose.

The Filibuster’s History

A filibuster is simply a procedural move intended to continue debating an issue or bill indefinitely, often for the purpose of either slowing down or avoiding a final vote.

It’s important to recognize that the Senate filibuster was not, and is not, part of the U.S. Constitution. The Constitution describes the Senate as a body that would normally operate on a majority-vote basis, and under only a few exceptions (e.g., impeachment and treaty ratification) is a supermajority required.

Both the House and Senate initially chose to operate under rules that included a “previous question” motion, which allowed a vote to be called on a main question, thereby making it possible to end debate.

(Note: The ability to “call the question” and end debate is a common tool still used, and sometimes abused, in all kinds of meetings. It typically needs a second, and then a vote is taken on whether to end debate.)

However, as president of the Senate, Vice President Aaron Burr in 1806 successfully persuaded the Senate to drop its debate-ending provision. But it wasn’t until the 1830s that the Senate minority initiated the first real filibuster, refusing to end debate. Even so, there were relatively few filibusters until the late 1800s.

By 1917, the unending filibuster came to a head under President Woodrow Wilson, when Senate Republicans filibustered Wilson’s effort to arm merchant ships at the beginning of the U.S. role in World War I.

Frustrated with procedural roadblocks to his agenda, Wilson wanted a process to end debate. So the Senate eventually adopted Rule 22, which said “cloture”—i.e., the ending of debate—could be invoked by a two-thirds vote of the senators present.

However, in 1975 the Senate made changes to Rule 22, including reducing the number for cloture from two-thirds to three-fifths (i.e., 60) of all sworn senators (not just those present at the vote).

In addition, filibustering senators no longer had to physically hold the floor, as had historically been the practice. As the Brookings Institution’s William Galston explains, “Today, senators block legislation via virtual filibusters that allow other business to be conducted while the filibuster remains operative.”

A senator need only inform the majority leader that he or she intends to filibuster a vote, which effectively halts the process until and unless the majority leader is able to round up 60 votes for cloture.

A senator can still filibuster the old-school way—as actor Jimmy Stewart did in Mr. Smith Goes to Washington. Senator Rand Paul (R-KY) did that for nearly 13 hours in 2013. But under current rules, a filibustering senator is not required to stand up in the Senate and talk or debate for hours on end. You might call it the lazy senator’s filibuster.

With that and other changes filibusters increased dramatically, from just a few per two-year congressional session in the 1960s, to 30 or 40 in the 1970s, to well into the hundreds when Democrats took over the Senate in 2007. And that’s where the filibuster stood until 2013.

Filibuster Work-Arounds

As a means of expediting budget-related bills, Congress passed the Congressional Budget Act of 1974, which created the “reconciliation” process. A bill moving under reconciliation can pass with a simple majority vote, and so cannot be filibustered.

It was first employed in 1980 and has been used for deficit reduction, welfare reform in 1996, the Bush tax cuts in 2001 and 2003, the Affordable Care Act in 2010, the Trump tax cuts in 2017, and most recently, the American Rescue Plan Act of 2021 (the Covid relief legislation).

While early reconciliation bills enjoyed bipartisan support, since 1993 the process has increasingly been used by both parties to bypass the filibuster and pass legislation along a party-line vote.

Because of the way the filibuster is currently practiced—especially the use of the “lazy filibuster”—it has become more of a roadblock than a “proceed with caution” sign. Instead of operating on a majority vote with only a few exceptions, as the Constitution envisions, the current Senate must find 60 votes to pass almost all legislation.

Recent Efforts to Limit the Filibuster

Frustrated that Republican senators were filibustering President Barack Obama’s nominees, then-Senate Majority Leader Harry Reid in 2013 convinced Democratic senators to do away with the filibuster for all presidential nominees except those nominated to the U.S. Supreme Court. Importantly, legislative bills would still be subject to the filibuster.

Republicans warned Democrats at the time that they would come to regret the day they made that change—as indeed they did. Not only was Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell able to confirm President Trump’s nominees and judicial appointments, McConnell followed Reid’s example and Republicans eliminated the filibuster for Supreme Court nominees, allowing the Senate to confirm Justices Neil Gorsuch, Brett Kavanaugh and Amy Coney Barrett.

Now that Democrats are back in charge of the Senate, they are threatening to do away with the filibuster on legislation. Republicans and conservatives are once again objecting and warning that Democrats will regret it when Republicans retake the Senate—and highlighting Democrats’ hypocrisy.

The Democratic Flip

Regardless of party, Senate majorities tend to resent the obstacle of the filibuster, while minorities treasure it. However, Senate Democrats have made a breathtaking reversal.

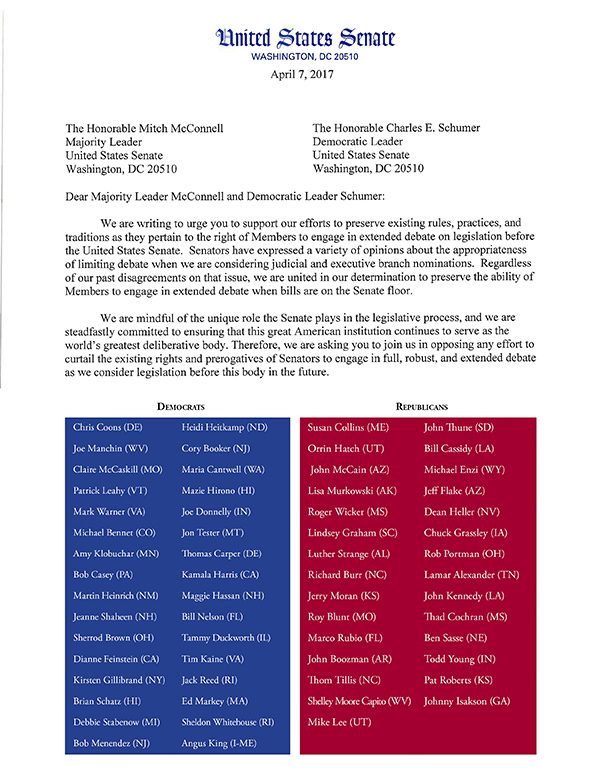

In April 2017, a bipartisan group of 61 senators signed a letter urging Majority Leader McConnell and Minority Leader Chuck Schumer “to support our effort to preserve existing rules, practices, and traditions as they pertain to the right of Members to engage in extended debate on legislation before the United States Senate.”—i.e., to preserve the filibuster with respect to “bills on the Senate floor.” [See the sidebar.]

Thirty-one Democratic senators and one independent who votes with Democrats, Angus King of Maine, signed that letter. Twenty-seven of them are still in the Senate. Yet only one of the Democratic signers, Joe Manchin of West Virginia, is today publicly objecting to ending the filibuster.

The left’s latest rhetoric is to claim the Senate filibuster was a creation of slave-holding states to protect slavery and was later used by southern segregationists—almost entirely Democrats, it must be said—to undermine voting rights and racial equality efforts.

But as the Washington Examiner’s Byron York has pointed out, that would mean those Senate Democrats who signed the 2017 letter, including Corey Booker of New Jersey and Kamala Harris of California, were explicitly demanding the retention of a Jim Crow legacy—which no one seriously believes.

Amend, Don’t End the Filibuster

While the Founding Fathers did not include the filibuster in the Constitution, it is in keeping with the Senate’s deliberative nature that protects the rights of the minority and minimizes the potential for what’s referred to as a “tyranny of the majority.”

U.S. Senate’s website declares: “The framers of the Constitution created the United States Senate to protect the rights of individual states and safeguard minority opinion in a system of government designed to give greater power to the national government. They modeled the Senate on governors’ councils of the colonial era and on the state senates that had evolved since independence… James Madison, paraphrasing Edmund Randolph, explained in his notes that the Senate’s role was ‘first to protect the people against their rulers [and] secondly to protect the people against the transient impressions into which they themselves might be led.’”

The 1975 reform that allows senators to filibuster legislation from the comfort of their office—or while on vacation—needs to be changed. Requiring filibustering senators to stand up in the Senate and debate an issue as long as one or more of them can hold the floor, as used to be the practice, wouldn’t eliminate the 60 votes necessary to end debate. But it would mean the “talking filibuster” wouldn’t continue indefinitely. A filibuster would slow the legislative process; but it wouldn’t kill it.

Conclusion

The Senate filibuster has a long history, including many changes and alterations. By slowing the legislative process, the filibuster can draw additional attention and force additional deliberation to prevent runaway legislation. As such it is in keeping with the original intent of the Senate. But today’s “lazy filibuster” has diverted the Senate from its constitutional design.

The filibuster has been effectively used by both political parties to slow down legislation, giving all sides more time to consider the options and, importantly, to come up with a compromise that is acceptable to a bipartisan majority. That was always the original goal of the Senate, and it still should be.