The irresponsibility is both bipartisan and bicameral, with members of Congress indiscriminately dipping into the public purse to purchase the affections of special interest groups galore.

As a result, Congress no longer makes a pretense at budgeting, if it ever did. But now the stakes are enormous, and congressional dalliance has become a real and present fiscal danger to the nation. What passes for congressional budgeting is a “budget process” so complex, so convoluted, and so dysfunctional, that no one including most Members of Congress knows what is going on. Institutional control over spending is absent.

Congressional “budgeting” lacks the two characteristics of real budgeting: binding budget constraints and enforceable spending priorities.

A real budget constraint is given objectively by one’s income. Congress effectively considers its only budget constraint to be the entire GDP of the country, which is to say it does not face an effective budget constraint because there is no operational and meaningful codified line between complete tax serfdom and responsible government. 1

Setting and enforcing priorities means not only establishing a well-ordered ranking of expenditure items from the most to the least important, but also a concomitant set of financial controls and procedures that ensures payment of top priorities (such as debt obligations, unfunded pension obligations, defense and public safety), first leaving all other needs, wants and desires to be paid out of what’s left. Congress neither sets priorities, nor spends money in a prioritized manner.

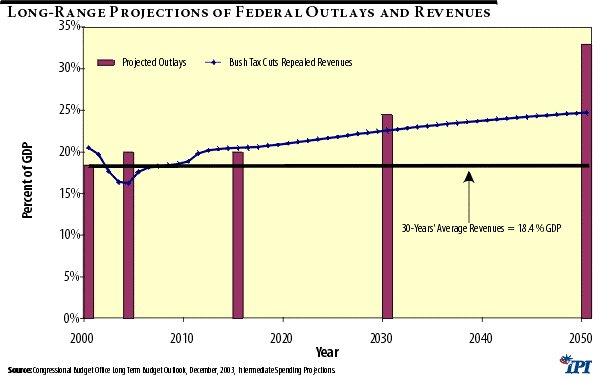

The Congressional Budget Office (CBO) recently published a long-range outlook for the federal budget that makes it clear congressional budgeting (an oxymoron to begin with) has completely broken down. After falling below 18.5 percent of GDP and being on a downward trajectory, spending has now risen back above 20 percent of GDP and is on an upward trajectory. Unless Congress does something to regain control over unbridled spending growth, CBO projects federal spending will gobble up an additional 5 percent of GDP by the end of the third decade of this century and just about a third of the nation’s output at mid-century. 2

Driving much of that projection is the $11 trillion unfunded Social Security liability. As the Social Security actuaries observed in last year’s Trustee’s Report, projected payroll tax income will begin to fall short of outlays in 2018, and will finance only 73 percent of scheduled annual benefits by 2043. 3

It does not have to be this way. The solution: personal retirement accounts.

Much has been written about the financial security that such accounts would bring to America’s workers. This is certainly true, as detailed below. But instituting a system of personal accounts would produce so many more benefits for the country as a whole. Namely, budget discipline would finally come to the U.S. Congress.

If workers were immediately allowed to invest at least half of their Social Security contributions in real assets, not only would Congress regain control of the federal budget. The next 14 years would provide time to begin generating sufficient wealth eventually to cover the entire unfunded Social Security liability — not just 73 percent of it — without tax increases or benefits cuts. And it would involve minimal additional federal borrowing, and no draconian cuts to federal spending.

Some Washington insiders such as Federal Reserve Chairman Alan Greenspan believe we have passed the point of no return, arguing that any Social Security reform must entail future benefit cuts. 4 To the contrary, just because Social Security in its current form cannot deliver on its promises does not mean they are extravagant or unrealistic. Social Security, like all socialistic schemes, results in social insecurity and a lower standard of living than would be possible through private enterprise.

If government required people to pre-fund their own retirement by saving in personal retirement accounts, benefits would exceed those promises, thanks to the rate of return possible in the private marketplace. 5 The problem is that Social Security does not work, not that the benefits it promises are too high.

Contrary to Mr. Greenspan, Social Security’s current actuarial inadequacy does not imply that the program “cannot afford” to pay the future benefits. It merely illustrates the inherent contradiction of asking one generation to forego saving for its own retirement in order to fund through taxes the older generations’ retirement. The dependency is perpetuated generation after generation.

Making Personal Accounts a Priority

Social Security’s crisis offers Congress a golden opportunity both to fix the nation’s retirement system and to begin fixing its own budget process. Each worker should be allowed to redirect at least half the payroll tax (6.2 percent of the current 12.4 percent payroll tax) into a personal retirement account. The transition would be funded through the higher returns those accounts will generate, by reasonable restraint in the growth of federal spending, and by prudent federal borrowing.

The key to the above is for Congress to:

- Immediately enact a law requiring federal spending growth to be 1 percentage point lower than projected each year for about eight years, unless both Houses of Congress vote by a substantial (say two-thirds) supermajority to allow spending growth to exceed the limit, assuming spending otherwise would remain at CBO’s 10-year baseline-20 percent of GDP;

- Enforce the spending growth limitation by automatically appropriating funds to the Social Security Administration at the beginning of each fiscal year in an amount equal to the sum to be saved as provided for in #1 above; and

- Set a truly binding long-run budget constraint to prevent future spending growth from driving federal spending above a fixed percentage of GDP, unless a supermajority (e.g., two-thirds) of each house of Congress votes specifically to do so.

In this way, Congress would require itself to pay its bills the same way millions of families and firms do so every month: priorities are set and paid for first, while everything is paid out of what’s left. Borrowing to meet capital needs, such as providing transition funding to rebuild the nation’s retirement system, is a perfectly sound financial management tool but it must be planned in advance and built into the budget.

Making good on the unfunded Social Security liability must be one of the nation’s top priorities. So each fiscal year, Congress should pay Social Security transition costs first out of the general fund before disbursing funds for anything else. That way, the money committed to pay for the transition to personal accounts will be paid up front at the beginning of each fiscal year, and the Congress will have the rest of the year to figure out how to live within the country’s means. It’s called “budgeting.”

This report sketches out how a spending-limitation budgeting process would work using the Progressive Personal Accounts Plan (PPAP) as a template for reform. 6

To be sure, it is not being suggested that the entire cost of fixing the nation’s retirement system be paid for by reducing other federal spending. Combined with relatively modest reforms in the way work, saving, investment, and entrepreneurial risk-taking are taxed, personal accounts would generate substantial new saving and investment and, consequently, a rise in federa To be sure, it is not being suggested that the entire cost of fixing the nation’s retirement system be paid for by reducing other federal spending. Combined with relatively modest reforms in the way work, saving, investment, and entrepreneurial risk-taking are taxed, personal accounts would generate substantial new saving and investment and, consequently, a rise in federal revenues. 7 The very creation of large personal retirement accounts will spur higher employment by reducing the cost of labor, and therefore generate more production. With reasonable spending restraint and sensible tax reforms, supplemental federal borrowing can be minimized and in fact paid back before mid-century.

Draconian cuts in federal outlays will not be necessary. In absolute terms, federal spending levels will continue to rise. All that is necessary is to lower the growth path of overall federal spending by slowing its growth rate about 1.5 percentage points a year from what CBO currently projects. By 2030, spending as a share of GDP would decline about four percent to 23.5 percent from the 24.5 percent that CBO projects if current trends continue. By 2050, overall federal spending need be only four-percent-of-GDP smaller than the 33 percent CBO currently projects under current trends (although, clearly, it would be more desirable economically if spending growth were restrained more). In other words, the amount of spending limitation required to help transform Social Security is only a beginning.

By itself, the spending limitation required to help finance the transition to personal retirement accounts will not cure Congress of its spending addiction. It will, however, provide a framework for extending the spending limitation mechanism to help transform other tax-and-transfer federal entitlements such as Medicare and in the process, one hopes, create a more disciplined congressional budgeting process.

Personal accounts not only would lead to real retirement security for the nation’s workers. They would result in stronger economic growth, and provide a built-in mechanism for spending growth restraint. All workers would have a strong financial interest in pressuring Congress to be fiscally responsible, since every dollar of reduced spending would go directly into their personal retirement accounts.

Averting Reform In The Name Of The Deficit

- Defn — A euphemism is a word or phrase that is used in place of a disagreeable or offensive term. When a phrase becomes a euphemism, its literal meaning is often pushed aside. In linguistics, the process of coining euphemisms is called taboo deformation. Euphemisms are also used to hide unpleasant ideas, even when the term for them is not necessarily offensive. This kind of euphemism is used extensively in the fields of public relations and politics.

Lies, Damn Lies, and Political Euphemisms

During the late 1990s the governing tension between a Democratic President and a Republican Congress brought the nation to the threshold of long-term budget surpluses at a record-high tax burden and a reduced level of spending not seen since the mid-1960s. With the election of 2000, that tension was relieved as Republicans assumed sole command of the elective branches of the federal government.

In fiscal terms, as the United States entered the 21st century it was as if the nation had returned to the years following World War II, before the Great Society explosion in government. Welfare reform had been enacted during the Clinton years, and the nation avoided a new extension of the welfare state by rejecting nationalized health care. As President Clinton left office, the nation stood at important crossroads.

Would Republicans continue to restrain spending growth and choose smaller, less intrusive government? Would they use Uncle Sam’s fiscal strength and borrowing power to achieve additional policy reforms, such as overhauling the economically harmful tax code and transforming Social Security? Or would the GOP opt for bigger, more intrusive government and greater dependency on the state?

It also was to be seen whether both political parties would use the political euphemisms of “fairness” (read: redistribution), “need” (read: spending), “fiscal discipline” and “deficit control” (read: tax increases) to perpetuate a heavy and rising tax burden and an ever-growing welfare state.

Surplus Reprise

Concerned about the misdirected debate taking place over budget surpluses and the national debt, and recognizing the coming fierce political battle over the surpluses, this author and co-author Steven Conover published a July 2001 report for IPI that attempted to debunk the “Washington Consensus” over surpluses and the national debt:

There is an almost uniform opinion among economists, policy makers and the general public that a persistent national debt is harmful to economic health. However, as a matter of economic and historical fact, the opposite is true. Modest deficits and prudent levels of government borrowing are nothing to fear because when incurred judiciously and used productively they can benefit-if not bless-a nation.

The practical result of this bipartisan consensus is political stalemate, in which Democrats use budget surpluses to block tax cuts, while Republicans use them to block spending increases. 8

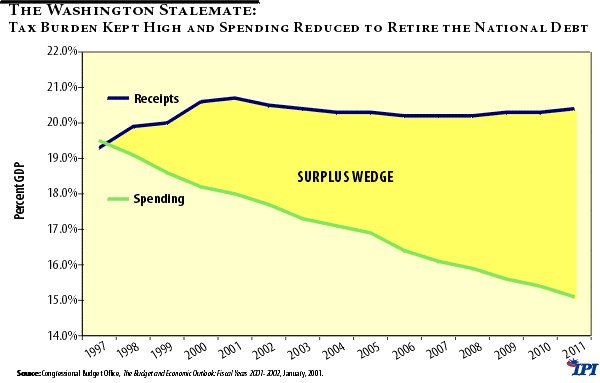

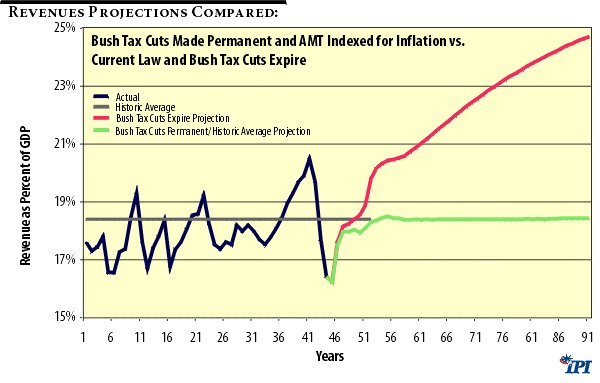

The political stalemate resulted in what the authors characterized as the “Battle of the Wedge,” illustrated in Figure 1 and presented in the previous IPI study.

Figure 1

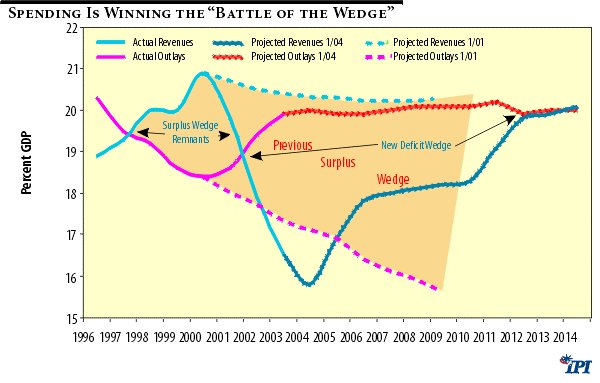

The “surplus wedge” in Figure 1, defined by CBO’s budget baselines, depicted the political battlefield over which the two stalemated forces would contend. But then, just as occurred during the aftermath of the 1981-82 recession (and the 1981 Reagan tax cuts), the surpluses projected prior to the 2001 recession (during which the Bush tax cuts were enacted) evaporated and now are not forecasted to emerge until well into the future, and then only temporarily. Figure 2 updates Figure 1 and superimposes the original surplus wedge on it for comparison.

The original surplus wedge has now been replaced by a deficit wedge as spending has risen almost completely to the level of previous revenue projections while revenues have been knocked down temporarily by recession and short-run effects of the Bush tax rate reductions. Figure 2 illustrates how the incredible revenue machine called the federal income tax will gradually drive revenues back up to converge with higher projected spending around 2011 if the Bush tax cuts are allowed to expire as provided for in current law. Thus the potent interaction of that revenue machine with special-interest politics ratchets the size of government ever larger.

Figure 2

Revenue Reprise

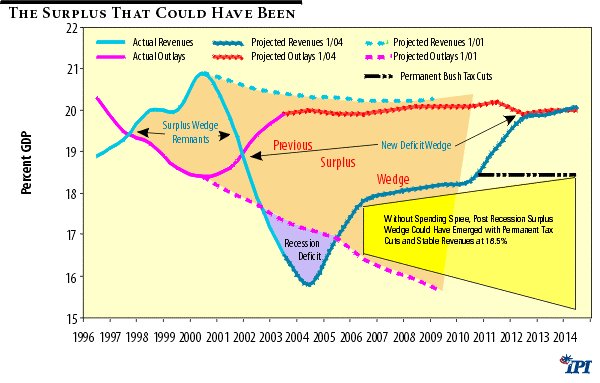

Clearly, spending is winning the battle of the surplus wedge. If spending had continued the downward trend (in relative, not absolute terms) that existed when President Clinton left office, even with recession and two rounds of tax cuts, 9 the budget would now be projected to come back into balance next year at around 17 percent of GDP, and budget surpluses would have emerged thereafter. (See Table 1.)

Table 1

At 17 percent of GDP, using the static scoring techniques employed by CBO, the budget would have been projected to stay in balance and go into surplus even if the Bush tax cuts were made permanent beyond 2010. Revenues would have stabilized at around 18.4 percent of GDP, the historic average during the past 30 years. 10 (See Figure 3 and Table 1.)

Figure 3

CBO puts into historical context the decision Congress soon will confront over whether to make the Bush tax cuts permanent or allow them expire in 2010: 11

- “Federal revenues have averaged 19.0 percent of GDP for the past 10 years, 18.4 percent for both the past 20 years and the past 30 years, and 18.3 percent for the past 40 years. For most of the period, revenues were far from the top of that range. They exceeded 19.5 percent of GDP on only three occasions in the past 50 years: 1969, 1981, and 1998 through 2001. The first instance resulted from a one-year income surcharge of 10 percent; the second was largely attributable to inflation-related bracket creep in the late 1970s and early 1980s; and the third was heavily affected by historically large capital gains realizations.” 12

- “Revenues are projected under the assumption that current tax law continues (including the scheduled expiration of the recent tax cuts). The latter assumption implies that average tax rates for individuals would rise well above any historical levels as both inflation and the growth of income above and beyond inflation (real growth) caused a large share of taxpayers to become subject to the alternative minimum tax (AMT) or to move into higher tax-rate brackets.” 13 (Emphasis added.)

Figure 4

Consequently, unless and until the current tax code is overhauled, periodically cutting tax rates does not undercut the revenue base as Senator Daniel Patrick Moynihan once accused President Reagan of doing, 15 and as many critics are now arguing about the Bush tax cuts. Periodic tax rate reductions simply check a voracious federal revenue machine from continually extracting a larger and larger share of private income. In fact, the actual situation under the current tax code is exactly the opposite of what Senator Moynihan and critics of the Bush tax cuts have charged. Leaving current tax law unaltered over any significant period of time acts as an automatic accelerator on the growth of government. 16

Spending Reprise

The 2001 Hunter/Conover IPI study predicted that the partisan political stalemate over surpluses would prove ephemeral and lead eventually to higher spending unless the stalemate were broken by replacing the misguided existing bipartisan Washington Consensus with a sound new bipartisan consensus:

- “The federal government should borrow additional funds each year sufficient to overhaul the tax code and to convert Social Security into a payroll-tax-financed, worker-investment retirement program. Sound borrowing to create a new tax code and a new investment-based retirement program will produce steady long-term growth, greater security and a higher standard of living than would rushing to pay off the debt at the expense of other more beneficial endeavors.” 17

Congressional Democrats quickly yielded to a Republican president on cutting taxes as an anti-recession strategy, but the misguided Washington Consensus was not replaced by a new sound consensus.

At the same time, “compassionate conservatism” in the White House, the pretext of “national security” after 9-11 and old-fashioned, bipartisan pork-barrel spending in the Congress combined to overwhelm the Washington stalemate on spending as federal outlays soared during the first three years of George W. Bush At the same time, “compassionate conservatism” in the White House, the pretext of “national security” after 9-11 and old-fashioned, bipartisan pork-barrel spending in the Congress combined to overwhelm the Washington stalemate on spending as federal outlays soared during the first three years of George W. Bush’s presidency. As Veronique de Rugy shows in a recent Cato Institute briefing paper, there has been a massive expansion in the federal budget and not simply because of higher national security spending in the aftermath of 9-11. 18 “Discretionary non-defense spending,” she shows, “has risen almost as rapidly as defense spending in recent years.”

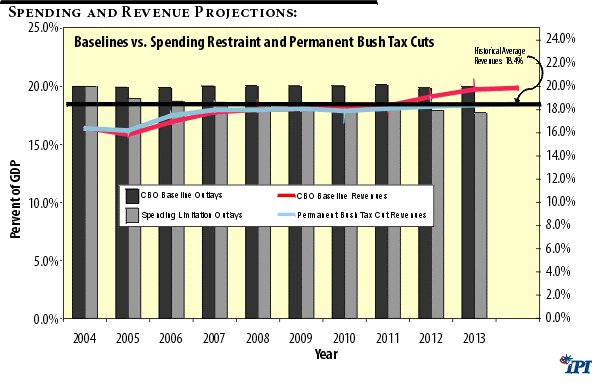

Figure 5 provides a framework and historical context in which to analyze the debate about whether to make the Bush tax cuts permanent. It compares the current CBO baselines to projected spending and revenue trends under a modest spending limitation and permanent Bush tax cuts including AMT reform. 19 (See also, Table 1.)

Figure 5

From Figure 5, it is unambiguously clear that repealing the Bush tax cuts without any form of spending limitation would result in balancing the budget up to 20 percent of GDP and rising. It is also clear that virtually all of the future deficits projected under current CBO baselines are the result of spending increases that drive spending well out of the historic range of federal revenues.

The conclusion is obvious and unavoidable: federal spending is out of control. 20

Federal outlays are expected to hit 20 percent of GDP this year. According to the CBO, if current trends continue, spending will rise to 24.5 percent of GDP by 2030 and to 32.8 percent by 2050. (See Figure 6.) Hence, no matter how fast the incredible federal revenue machine sucks in taxes, unless some kind of spending limitation is put into law, it will never be sufficient to keep pace with spending.

Figure 6

Under these circumstances, “deficit hawks” will continually cry for tax increases in the name of “fiscal prudence.” If Congress and the president yield to their braying, however, it will be self-defeating. Raising tax rates in pursuit of accelerating spending growth will only drag down economic growth and revenues right along with it.

Euphemizing Social Security and Debt

Woven into the very fabric of the Washington Consensus on deficits and the public debt is another misconception born of euphemism, namely that using the excess revenue generated by the payroll tax to pay off debt or lower deficits somehow constitutes an “investment” that partially “pre-funds” workers’ retirement and represents a “down payment” on the $11 trillion dollar unfunded Social Security liability.

By 2000, Congress had for 17 years routinely raided Social Security payroll tax revenues not needed to pay benefits, using them to pay for everything else in the federal budget, from paper clips to battleships. In exchange, the Treasury placed IOUs in the so-called Social Security trust fund, promising to pay back the pilfered payroll-tax revenue with interest. 21 Economists, politicians and the general public deluded themselves that generating these excess payroll tax revenues and then immediately spending them on non-Social Security programs constituted a shift away from a pay-as-you-go government spending program to a pre-funded pension plan, even though none of the money was ever invested in anything.

The myth that by overcharging workers on their payroll taxes Social Security was building up a real “reserve” — conveniently contrived even earlier by opponents of reforming Social Security with personal retirement accounts-was a special case of the more general “public-saving” fallacy used by former Treasury Secretary Robert Rubin and Fed Chairman Alan Greenspan during the Clinton years to justify increasing taxes to “lower the deficit” or “run a surplus.” Politically, “Rubinomiacs” (those who practice “Rubinomics”) are the Democratic version of Republican “deficit hawks.” Combined, they form the basis of the fallacious Washington Consensus on debt and deficits that places budget deficits über alles.

During the second half of the 1990s, Rubinomics became a political bulwark against taxpayers' demanding the return of budget surpluses through tax cuts, or, alternatively, against workers being allowed to place at least their excess payroll taxes into personal retirement accounts, which would constitute real, if only partial, pre-funding of pensions.

The grandest of recent political euphemisms — “public saving” (read: excessive taxation) — can be traced to the 1983 Greenspan Commission’s attempt to save Social Security from “insolvency” by raising taxes. The Greenspan Commission convinced Congress to raise the payroll tax by construing as real saving and investment the purely internal government bookkeeping convention of a so-called Social Security “trust fund.” 22 Politicians of all stripes began deforming the taboo of “excess taxation” 23 by calling it “public saving.”24

The key to perpetuating the raid on Social Security revenues, which continues to this day, has been politicians’ ability to perpetuate the public The key to perpetuating the raid on Social Security revenues, which continues to this day, has been politicians’ ability to perpetuate the public’s acceptance of excessive payroll taxes through a flurry of euphemisms. They delude workers into believing that these excess taxes are somehow “invested” and earning a real rate of return, building up a reserve that later could be drawn upon to help pay future benefits.

But of course, nothing could be further from the truth. Once excess payroll tax revenues come through the U.S. Treasury door, there really is nothing else to do with them but spend them, either on government programs or to service the national debt. 25

The pertinent economic question, therefore, is simply: does either government spending or paying down public debt yield a higher rate of return to society than the alternative productive uses to which that money could be put in the private sector? The empirical evidence suggests that cutting tax rates and/or allowing the payroll tax to be redirected into personal retirement accounts, with the transition costs at least partially offset by slower growth in government spending, will result in higher returns. 26

But the question was never asked that way in the 1990s. Instead, the discredited fiscal theory propounded by former Clinton Treasury Secretary Robert Rubin and Fed Chairman Alan Greenspan simply assumed, contrary to empirical evidence and without offering supporting empirical evidence of their own, that government borrowing crowds out more private investment than is crowded out when taxes are extracted from the private sector to reduce the government debt. 27 Deficit hawks and Rubinomiacs simply do not go to the real heart of crowding out: government spending.

In 1998, so much excess revenue was flowing into the government, not only from payroll taxes but also from the income taxes and capital gains taxes, that the resulting budget surpluses stripped away the veil that heretofore had covered the naked raid on Social Security: using excess payroll taxes to fund non-Social Security government programs. But rather than yield up some of these surpluses and send them back to voters, deficit hawks and Rubinomiacs demanded more surpluses. 28

If overtaxing workers through the payroll tax was justified to raise “public saving” and “strengthen Social Security,” and if raising taxes (as Clinton did in 1993) was justified to reduce deficits and decrease “public dissaving” (another euphemism for deficit spending), wasn’t it all the more justified to continue general-purpose over-taxation when those deficits disappeared in order to run surpluses and increase “public saving”?

Whether the budget was in deficit or in surplus, deficit hawks and Rubinomiacs had hit upon a general, all-purpose, pseudo-scientific justification for perpetually overtaxing workers, savers and investors.

In the late 1990s, during the heyday of Rubinomics, it became fashionable in Washington to extend the euphemism of “public saving” beyond the Social Security trust fund to budget surpluses generally. The government would force the public to save more by taxing them more. The problem is that the notion of increasing saving by using taxation to reduce consumption (i.e., aggregate demand) ignores the offsetting supply-side effect that taxes have on depressing private saving. 29

The false premise underlying Rubinomics and the “crowding-out” thesis popularized by deficit hawks — call them “demand-side fiscalists” — is that the marginal tax dollar spent by the government is more productive than that spent by the private sector. Not only is there a lack of empirical evidence verifying this assumption, but a plethora of evidence contradicting it. At current (excessive) levels of government spending and current (modest) levels of public debt, there is considerably more than a dollar in deadweight loss incurred each time an additional tax dollar is extracted from the private sector, whether that dollar is spent on government programs or to retire part of its debt.

If debt reduction is the objective, by far the more efficient choice is to reduce spending on negatively yielding government programs, reduce that dead-weight loss on the economy and devote the savings to pay off debt. However, as the 2001 Hunter/Conover IPI study demonstrated, an even more efficient course is to reduce spending on negatively yielding government programs and earmark the savings for personal retirement accounts. The key is to reduce government consumption in order to increase personal wealth, which is precisely what is proposed in PPAP.

If the demand-side fiscalists remain successful in deluding the public that deficits and debt are the nation’s first-order fiscal priorities, it will be impossible to convince voters that it is worth borrowing more money today to pay Social Security benefits while establishing personal retirement accounts. Just as Rubinomiacs and deficit hawks always prescribe higher rather than lower taxes to tackle deficits and debt, so too do demand-side fiscalists invariably prescribe higher taxes and/or lower Social Security benefits to head off the system’s impending implosion. That is worst than a mistake; it is a contradiction.

Investor Nation: Making Every Worker An Owner

No budget trend is inevitable, but all signs point toward larger, more encompassing government. The huge new Medicare prescription drug entitlement enacted last year (now estimated to cost $534 billion during the first decade) suggests we are on a one-way path toward an American version of Euro-socialism, what Alexis de Tocqueville characterized as democracy’s “velvet tyranny,” or more popularly today, the “nanny state.” 30

It is not too late to avert a descent into that quagmire. Avoiding de Tocqueville’s velvet tyranny, however, will require a big idea, bold political leadership, and reconfigured incentives.

The big idea is to turn every American into an owner of financial assets through instituting personal retirement accounts. The assets not only can be accumulated over one’s working lifetime to provide for retirement, but more generally this can become the basis of an investor nation in which every American has an incentive to demand public policies hospitable to work, saving, investment, and entrepreneurial risk-taking.

Whereas the nanny state offers the false hope of security in exchange for high taxes and forfeited freedom, which leads to exploitation of the public fisc for concentrated personal gain, an investor nation promises wealth and opportunity for everyone willing to work, save and invest, which would lead to broad-based voter support for federal spending control and other growth-enhancing policies.

The big idea, therefore, is to allow all workers to place into personal retirement accounts at least half (6.2 percent) of the payroll tax they and their employers currently pay, without cutting promised Social Security benefits or increasing taxes. The added transition cost of redirecting the payroll tax into the accounts would be financed through reasonable government spending restraint, pro-growth tax reforms and prudent federal borrowing.

Social Security Reform In a Nutshell: the Four Principles

President Bush is seeking a mandate to redirect a portion of Social Security payroll taxes into personal retirement accounts. This presents an historic opportunity to transform Social Security, a pay-as-you-go, tax-and-transfer government-benefits program, into an investment-based, pre-funded private retirement plan.

The Alliance for Retirement Prosperity, a coalition of some two-dozen advocacy groups co-chaired by Dick Army, Jack Kemp and former Social Security Commissioner Dorcas Hardy, has put forward the following four principles to guide the design of personal-accounts legislation:

- Make personal retirement accounts large enough — at least half the payroll tax (6.2 percentage points) — to provide adequately for workers' retirement without the need for a permanent, supplemental tax-financed, government benefits component, except to provide a safety-net and, initially, to finance the disability component of the program.

- No future benefit cuts. This includes stealth benefit cuts such as switching the method of calculating initial benefits from wage to price indexing. This principle not only should apply to workers who choose to remain in Social Security as we know it, who should receive all promised benefits scheduled in current law. It also must apply to those who opt into personal accounts but who are too close to retirement to realize their full benefit and, therefore, must rely on supplemental government benefit payments or recognition bonds to supplement their personal account income. Everyone currently participating in Social Security (roughly anyone born before 1990) should do at least as well under the new system as they are scheduled by law to do under the current system.

- No tax increases. This includes stealth tax increases such as further hikes in the retirement age.

- Finance the transition to personal accounts through a combination of federal spending-growth restraint, federal borrowing and the increased tax revenues produced by the higher economic output. The added output would be generated by the switch to personal retirement accounts and additional tax reforms to raise the return on work, saving, investing and entrepreneurial risk-taking.

The only extant legislative proposal that meets these principles is the “Social Security Personal Savings and Prosperity Act of 2004” recently introduced by Congressman Paul Ryan (R-WS) and Senator John Sununu (R-NH), which in large part is patterned after the “Progressive Proposal for Social Security Personal Accounts” plan described in IPI Policy Report # 176 (henceforth called the Progressive Personal Accounts Plan or PPAP). The Chief Actuary of the Social Security Administration has scored the PPAP proposal as “actuarially sound”.

Social Security Administration Chief Actuary Stephen Goss has scored PPAP as 'actuarially sound' under two basic assumptions: (1) Federal spending growth is limited sufficiently so that the overall level of federal outlays is held about 1.5 percent of GDP below what it otherwise is projected to be (18.5 percent versus 20 percent for a dozen years); 31 and (2) increased national saving resulting from new investment generated by the transformation of Social Security to a saving and investment vehicle (projected to equal about 2.9 percent of GDP) will generate additional tax revenue, which will be earmarked to finance the transition from the current pay-as-you-go system. (Goss does not take into consideration additional economic growth and dynamic revenue effects that could be expected if these reforms were accompanied by fundamental tax reform to increase further the return on work, saving, investing and entrepreneurial risk-taking. 32)

According to the Chief Actuary's score, with these two legs of transition funding in place, the net transition deficits would average $52 billion (constant 2003 dollars) a year over the first 24 years. New public debt, including accrued interest, would rise by a total of $1.82 trillion (constant 2003 dollars), actually reducing the debt's share of GDP to 29 percent from 38 percent today. Sufficient surpluses would be produced after 2028 to pay off all the new borrowing within 15 years, leaving the net impact on debt held by the public at zero after less than 40 years.

The status quo is unthinkable. Continuing Social Security as we know it would add $1.6 trillion (constant 2003 dollars) to federal debt held by the public by 2028, leaving the national debt exactly where it is today (assuming Congress balances the rest of the budget) at 38 percent of GDP. By mid-century, the national debt would exceed the nation's annual output. During the next quarter-century, annual deficits would approach 15 percent, and the national debt would skyrocket to 350 percent of GDP.

Deficit-Hawk Divergence

Strong disagreement among personal-accounts proponents, stemming from profoundly different views regarding the economics and politics of public borrowing, has prevented a united front around the four principles. The deficit-hawk faction tends to agree on the following propositions: (i) Congress will not reduce spending growth significantly so spending savings should not be counted as a partial means of financing the transition; (ii) moving to personal accounts will simply displace existing savings without producing much if any new savings, and Congress is unlikely to enact significant tax reforms, therefore increased output should not be counted on to produce higher revenues to help finance the transition; and (iii) the nation cannot afford to borrow significantly to finance the transition.

Holding themselves hostage to these propositions, usually in the name of “solvency,” the deficit hawks among personal retirement accounts proponents have convinced themselves that future benefit cuts are inevitable whether or not Social Security is “reformed.” Because they discount virtually all means of transition-financing save future benefit cuts, they have tended to become obsessed by a belief that large (i.e., 6 percent) accounts without future benefit cuts would require annual deficits of intolerably large proportions (rising to 6.5 percent of GDP after 75 years, albeit still less than half the 15 percent deficits coming under current law).

Thus, the deficit-hawk faction among personal-account proponents cannot embrace all four principles and therefore is driven to accept at least one of the following two untenable conclusions:

- They believe that even though the rate of return on payroll taxes paid to support the current Social Security program is a very bad deal for workers (less than 2.0 percent on average for workers born in 1960 and worse, even negative in some cases, for those born later), under personal accounts future benefits still must be cut significantly. Even during the transition period, the deficit-hawk faction would cut future benefits about 30 percent by restricting to no more than about 70 percent of scheduled benefits both the benefits paid to those who elect to stay in Social Security and the supplemental benefit payments (or “recognition bonds”) paid to those who elect personal accounts but were too old at the accounts’ inception to have been in them long enough to enjoy their full benefits; and/or

- They think personal accounts must be kept small enough (e.g., 2.5 percent of payroll) to keep transition costs “affordable” over the near term, even though these small accounts would be insufficient to eliminate long-run actuarial deficits and restore “solvency” without future benefit cuts.

The fierce disagreement between personal-account proponents who accept the four principles and those who do not threatens to undermine efforts to enact significant Social Security reform.

How Great the Growth Impact?

Harvard economist and former Council of Economic Advisers Chairman Martin Feldstein estimates that moving to a pre-funded retirement system via private accounts would increase economic output about 3 percent per year in perpetuity. While the magnitude of this estimate may be subject to debate, the general conclusion is not. New saving would result from replacing a payroll tax with a forced saving requirement through which workers acquired real assets. There is no doubt that this would remove significant labor-market distortions and lead to an increase in the capital stock, and hence higher economic growth and an increase in tax revenues. The only question is, how much?

Some supply-side critics (as distinguished from the demand-side fiscalists) caution that given the tax code’s harsh treatment of capital, much of that new flood of saving will flow into global capital markets in search of a higher after-tax rate of return than it can fetch in the U.S. economy. 33 Consequently, many supply-side advocates of large personal accounts add a caveat to their support, to wit: the creation of such accounts must be accompanied by significant federal tax reform to raise the after-tax rate of return to capital.

Is Spending Restraint Politically Possible?

Numerous critics of PPAP discount the use of a spending-restraint provision to fund part of the transition because they believe it is politically infeasible. That view, of course, is a political judgment, not an economic or actuarial fact.

The Chief Actuary felt comfortable making the assumption, not because he necessarily trusted Congress to make the required spending decisions but because the savings from the spending growth restraint provision in the plan are buttressed by stringent institutional rules to enforce the spending-growth speed limit. At the beginning of each fiscal year, transition funds would be appropriated automatically from the Treasury's General Fund into the Social Security Trust Fund for use in filling any revenue gaps created by redirecting half the payroll tax into personal retirement accounts. Congress then would have the rest of the year to decide what other spending to restrain in order to make up the difference.

Proponents of personal accounts who discount the likelihood of spending-growth restraint overlook the profound change in the public-choice calculus that would occur under a spending-limitation provision such as the one contained in PPAP. If Congress desired to exceed the spending-growth speed limit, it would have to vote by a two-thirds supermajority to do so, enact a tax increase and/or allow the deficit to rise. Therefore, for the first time, the rules would be stacked heavily in favor of spending-growth restraint.

In one fell swoop, every worker in America would have an incentive to pressure Congress to reduce spending growth because every dollar of reduced spending on special interests and corporate pork would go directly into their personal retirement accounts. The public interest would gain the upper hand over special interests, and every worker in America would have a powerful incentive to enforce the spending speed limit by pressuring Congress to keep spending growth within bounds because every dollar of reduced federal spending would go directly into their personal retirement accounts. The electorate also would come to understand the true fiscal prudence of incurring a manageable public debt to effect the transition from the old welfare-state regime to the new investor-nation regime.

Battling for the Heart and Mind of the President

President Bush supports redirecting part of the payroll tax into personal retirement accounts, but it is not yet clear into which camp the Administration actually falls: large accounts or small accounts? Future benefit cuts or no benefit cuts? Additionally, will the Administration embrace debt finance as an essential financial tool to transition into personal retirement accounts, or will it adorn the plumage of a deficit hawk and avoid public debt as the new political third raid? Will it boldly commit itself to making good on scheduled Social Security benefits promised under current law, whether or not a worker chooses personal accounts? Or, will it succumb to debt-phobia and restrict the size of accounts and/or limit participation with income caps and phase-outs? Will the administration restrain the growth of other federal spending or cut future benefits by resorting to stealth techniques such as switching from wage indexing to price indexing in the initial determination of benefits and/or computing the size of recognition bonds?

While the answers to these questions are not yet clear, what is crystal clear is that all three options for reform presented to President Bush by his Presidential Commission to Strengthen Social Security fall clearly within the “demand-side fiscalists” framework, relying on small accounts (as called for by all three models in the Commission’s report), 34 benefit cuts (under Model 2) and a complete aversion to spending restraint and debt financing (all three models). 35

Meanwhile, the “preserve-Social-Security-as-we-know-it” camp will fight a rear-guard action against personal retirement accounts. (See for example the proposal of Brookings Institution senior fellow Peter R. Orszag and Massachusetts Institute of Technology professor Peter A. Diamond. 36 ) They are, however, unlikely to convince the public that the old New Deal program can be resuscitated with a nip in benefits here and a hike in taxes there. A March 16, 2004 poll done for USA Next by McLaughlin & Associates found that 62 percent of the general public support allowing workers to redirect half the payroll tax into personal accounts. Support for large accounts increases to 68 percent if the question makes explicit that everyone would be guaranteed to receive no less than they are promised under the current Social Security system. Support plummets to 20 percent with 62 percent opposing if respondents are ask specifically whether they would support benefit cuts. 37

The greatest threat to Social Security becoming a platform on which to build a 21 st century investor nation, therefore, comes not from a fearful or ignorant public. It comes from inside-the-beltway demand-side fiscalists in both political parties, on Capitol Hill and inside the Administration — who all the while give lip-service or perhaps even sincere support to personal retirement accounts. Indeed, the battle is shaping up as it did in 1980 when deficit hawks within in the Republican Party did their utmost to sabotage the Reagan Revolution before it got off the ground-all in the name of “fiscal prudence.”

Today’s demand-side fiscalists tend to support personal retirement accounts but insist that they be “paid for” — a euphemism for cutting future benefits or raising taxes. Some demand-side fiscalists support using personal accounts to replace at least part of Social Security (a so-called “carve out”) while others support personal accounts only if they are an add-on to the existing Social Security system. In both cases, however, demand-side fiscalists view personal accounts not as a tool to transform America into a 21st-century investor nation, but rather as one more technocr Today’s demand-side fiscalists tend to support personal retirement accounts but insist that they be “paid for” — a euphemism for cutting future benefits or raising taxes. Some demand-side fiscalists support using personal accounts to replace at least part of Social Security (a so-called “carve out”) while others support personal accounts only if they are an add-on to the existing Social Security system. In both cases, however, demand-side fiscalists view personal accounts not as a tool to transform America into a 21st-century investor nation, but rather as one more technocratic approach to “restore solvency and balance” to a gigantic government-transfer program.

Consequently, many demand-side fiscalists are willing to content themselves with small (e.g., 2.5 percentage points of payroll) accounts that leave the basic tax-and-transfer engine in place. However, whether they support small or large personal accounts, most demand-side fiscalists insist that before such accounts are inaugurated, something must be done within the confines of the existing program (i.e., raise taxes, cut benefits, raise the retirement age, increase taxation of benefits and so forth) to “make the program solvent.” 38

An Opportunity for Economic and Political Transformation

Proponents of using the Social Security platform to create an investor nation define the challenge not as fixing Social Security or making it solvent — it is unfixable and can only be made to appear solvent on paper-but rather to transform it into a vehicle for making every worker an owner of assets.

If Social Security is properly transformed into an investment-based opportunity for workers to save and invest at least half the current payroll tax, the matter of long-run actuarial solvency will take care of itself as the marvel of compound interest took over.

This “radical” appeal to the power of markets, of course, will provoke the same hue and cry that was heard 25 years ago about Ronald Reagan’s tax rate reductions — "riverboat gamble," “risky scheme,” “voodoo economics,” “free lunch,” “snake oil,” etc. And the economists associated with the four principles will be disparaged as “out of the mainstream” and “not credible.” If the president and the Congress yield to this kind of debt hysteria and hold themselves hostage to false fiscal constraints — which invariably will lead to small accounts, future benefits cuts, and/or tax increases-they will squander the greatest opportunity for political and economic transformation since the New Deal.

Retirement Income Will Rise

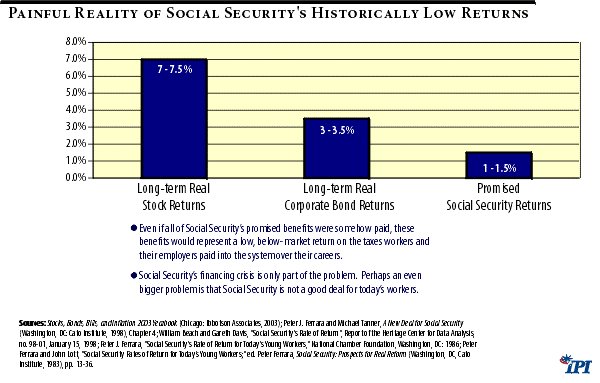

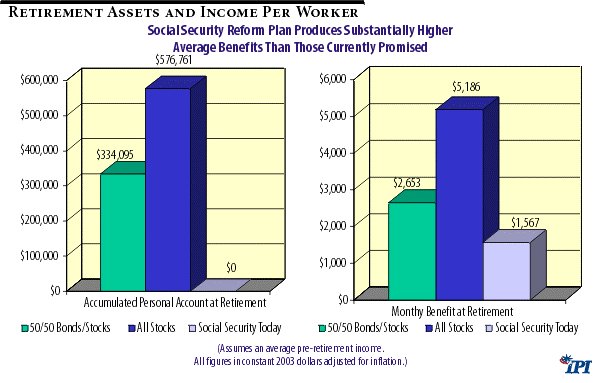

The greatest irony about the debate on the Right over whether to cut future Social Security benefits is illustrated in following series of tables. Figure 7 demonstrates that the benefits Social Security promises but cannot pay are a very bad deal for American workers. Those who would “make Social Security solvent” by cutting future benefits propose to “fix” Social Security by making a bad deal even worse.

Figure 7

Figure 8 compares the retirement income of an average worker under Social Security to what he or she could expect under PPAP.

Figure 8

The average-income worker is assumed to be age 40 today earning $35,000 this year. He entered the work force at age 23 earning $17,677 per year with wage increases each year equal to the average annual wage increase in the economy.

With a portfolio of half stocks and half bonds, at standard market investment returns the worker would reach retirement with $334,095 (all numbers in 2003 constant dollars). That fund would be sufficient to pay an annuity about 70 percent higher than what Social Security promises but cannot pay, $2,653 per month compared to $1,567.

With a higher percentage invested in stocks, the account would pay even more. With the accounts invested entirely in stocks and earning standard market returns, the worker would retire with a fund of $576,761, paying $5,186 per month, well over three times what Social Security promises but cannot pay. Some have suggested that the personal accounts could just be invested in an S&P 500 index fund, which could be expected to provide these returns and results. Accounts invested in stocks more than 50 percent but less than 100 percent would produce results proportionally within these two calculations. 39

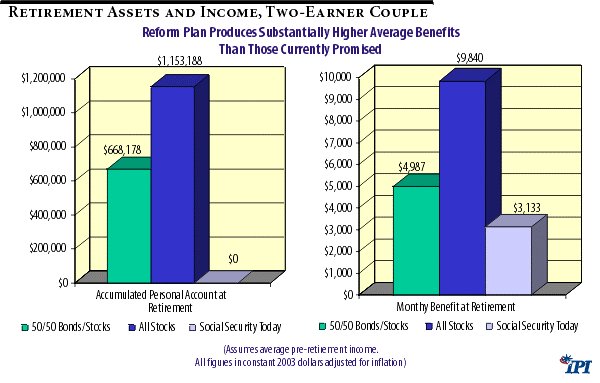

Figure 9 makes the same comparisons for an average two-earner couple where the husband and wife are both 40 today. The husband earns an income of $40,000 per year and the wife earns an income of $30,000, which is consistent with U.S. Census Bureau data regarding the average income of two-earner married couples. They again each entered the work force at age 23, with the husband earning $20,202 that year and the wife earning $15,152. They also each earn only the average salary increase each year. The calculation assumes each was able to exercise the account from the beginning of their careers.

Figure 9

With the account invested half in stocks and half in bonds, at standard market investment returns the couple would reach retirement with $668,178. That account would be sufficient to pay them 60 percent more than Social Security promises but cannot pay; $4,987 per month compared with $3,133.

With more of the account funds invested in stocks, the account benefits would be even higher. And with the account invested entirely in stocks, at standard market returns the couple would reach retirement with an account of $1,153,188. That fund would be sufficient to finance a monthly benefit of $9,840-more than three times what Social Security promises but cannot pay.

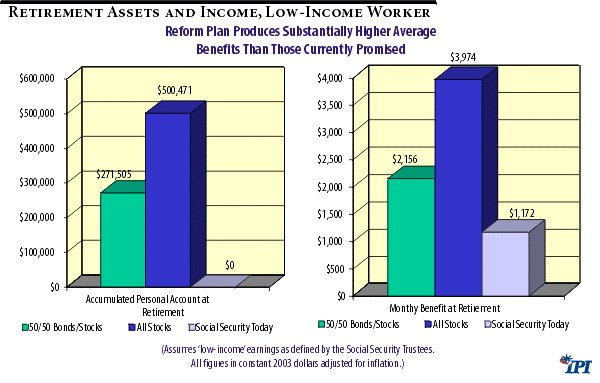

Figure 10 makes the same comparisons for low-income workers.

Figure 10

The Washington Establishment has spied the looming fiscal crisis brought on by out-of-control spending as a golden opportunity to consolidate its hold on American taxpayers and ratchet up the size of government in the name of “fiscal prudence.” Consequently, the coming political battle over how Social Security will be “reformed” to restore its solvency will be about much more than simply how to “reform” this socialistic vestige of the New Deal. The political confrontation will, in part, determine whether de Tocqueville’s darkest fears are realized, or whether free markets and free individuals will reassert themselves and realize their full potential. The debate shaping up over Social Security is even larger than the battle over economic policy that played out during the early 1980s between Ronald Reagan and his “supply-side” advisers who were on one side, and the bipartisan coalition of “deficit hawks” on the other who stood against the Reagan reforms in the name of “fiscal prudence.” This time, one side will consist of those advocating reductions in federal spending growth and prudent federal government borrowing in order to enact large personal retirement accounts without raising taxes or cutting future benefits. Pitted against them will be a coalition of die-hard New Dealers who want to preserve Social Security as we know it, joining forces with demand-side fiscalists who might even support small personal retirement accounts but will demand tax increases and benefit cuts to “pay for” them, all in the name of “fiscal prudence.” Fed Chairman Alan Greenspan, for example, sees the pending insolvency of Social Security as a deficit problem. Just as he and other demand-side fiscalists have been in favor of excessive payroll taxes as a general fiscal strategy to hold down deficits, they are now prepared to cut Social Security benefits to hold down deficits so government can grow to obese proportions. As head of the Greenspan Commission in 1983, the Fed chairman convinced President Reagan and Congress that workers should pay higher taxes so they could enjoy their full promised Social Security benefits when they retired. Two decades later, Greenspan and his cohorts say those same workers should accept benefit cuts because the previous bailout didn’t work. |

Financing The Transition, Reaping The Rewards

To recap, the Chief Actuary’s official score of the Progressive Personal Accounts Plan illustrates that with proper transition funding, workers’ retirement income can rise, and the increase can be accomplished without raising taxes or borrowing an exorbitant amount of money. With increased national saving and improved labor market incentives resulting from personal retirement accounts, especially if accompanied by reforms to the tax code, the capital stock of the nation will rise and economic growth will increase. 40 Federal revenues, therefore, will be higher and federal borrowing lower than they would be in the absence of the personal accounts. 41

Dynamic Economic Growth Effect of Personal Accounts

The Chief Actuary’s official score factors in the equivalent of a constant 2.9 percent-of-GDP revenue feedback effect from a larger economy due to greater saving and investment spurred by the creation of the personal retirement accounts. This dynamic revenue feedback effect, which the Chief Actuary labels “Corporate Revenue Recapture,” is not calculated from the Chief Actuary’s own economic model but rather is assumed based on Harvard Economist Martin Feldstein’s research, which the Actuary had used previously in scoring Senator Phil Gramm’s personal accounts plan in 1999. 42

The Chief Actuary accepted Feldstein’s estimate that “The combination of the improved labor market incentives and the higher real return on saving has a net present value gain of more than $15 trillion, an amount equivalent to three percent of each future year’s GDP forever.” The Chief Actuary accepted Feldstein’s estimate that “The combination of the improved labor market incentives and the higher real return on saving has a net present value gain of more than $15 trillion, an amount equivalent to three percent of each future year’s GDP forever.” 43 This increase in output compares to an infinite-horizon present-value unfunded Social Security liability equal to $13 trillion when measured correctly. 44

Feldstein broke down his estimate into two pieces. One-third of the effect (1 percent) derived from removing the labor market distortions caused by the payroll tax, which he estimated results in a “deadweight loss of approximately one percent of each year’s GDP in perpetuity, an amount equal to 20 percent of payroll tax revenue.” 45

The remaining 2 percent of GDP deadweight loss derives from “the loss of investment income that results from forcing employees to accept the low implicit return of an unfunded program rather than the much higher return on real capital that would be paid on private saving. The present value of the annual losses from using an unfunded rather than a funded system substantially exceeds the benefit to those who received windfall transfers when the program began and when it was expanded. ” 46 (Emphasis added.)

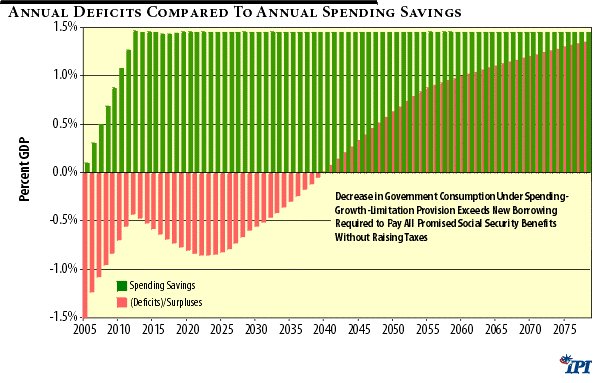

The spending limitation provision illustrated in Figure 11 is similar to the one proposed in the “Social Security Personal Savings and Prosperity Act of 2004,” recently introduced by Congressman Paul Ryan (R-WS) and Senator John Sununu (R-NH), which in large part is patterned after the “Progressive Proposal for Social Security Personal Accounts” plan described in IPI Policy Report # 176.

The importance of these conclusions cannot be overemphasized. They imply that the entire transition cost can, in theory, be borrowed. And the amount by which future taxes will be higher (to repay the debt) than they would be in the absence of the borrowing will be less than the gains future generations will realize from the reform. Hence, future generations voluntarily would elect to pay the higher tax implied by the debt to enjoy even higher returns on the personal accounts, which on net would leave them better off. That is, the current tax-and-transfer scheme is so inefficient that moving to pre-funded personal retirement accounts constitutes a Pareto superior policy that leaves everyone at least as well off.

While most economists recognize the labor-market improvement that would occur by moving to personal accounts and funding retirement fully, some supply-side economists are skeptical that the dynamic effect of increased saving and investment — whatever the actual magnitude of it — would fully apply to the U.S. economy under the current federal tax code. In a global capital market, new saving would seek the highest possible rate of return and given the harsh manner in which the current federal tax code treats returns to saving and investment, a substantial portion of the redirected payroll taxes may flow not into new plant and equipment in the United States but into global capital markets. While individual workers still would enjoy the full increase (however large that may be) in return on their investment over what they currentl While most economists recognize the labor-market improvement that would occur by moving to personal accounts and funding retirement fully, some supply-side economists are skeptical that the dynamic effect of increased saving and investment — whatever the actual magnitude of it — would fully apply to the U.S. economy under the current federal tax code. In a global capital market, new saving would seek the highest possible rate of return and given the harsh manner in which the current federal tax code treats returns to saving and investment, a substantial portion of the redirected payroll taxes may flow not into new plant and equipment in the United States but into global capital markets. While individual workers still would enjoy the full increase (however large that may be) in return on their investment over what they currently can expect from Social Security, the U.S. economy per se may not be the beneficiary of the investment. Supply-side skeptics argue, therefore, that Feldstein has overestimated the extent to which moving to personal accounts would result in higher federal revenue recapture. 47

The supply-side critique does not imply that large personal-account reform is undesirable or unachievable; it means that serious consideration should be given to accompanying personal account reform with significant tax reform. This would ensure that national saving is maximized and that it fully translates into a higher rate of return to capital, increased domestic output and higher federal revenues, which would ensure adequate financing for the transition. Two specific tax reforms that supply-side proponents of large personal accounts contend would accomplish this are: eliminating the multiple taxation of returns to saving and investing; and allowing businesses to expense all investment in plant, equipment, technology, and inventories.

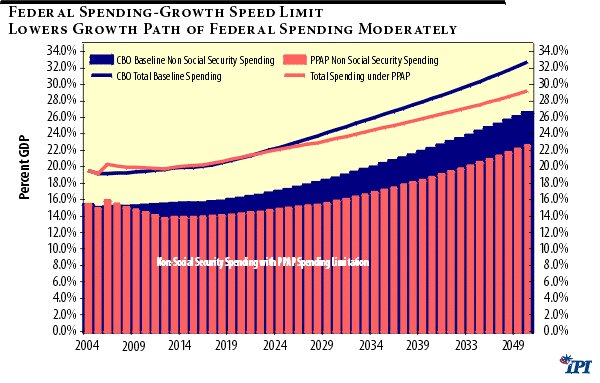

Lowering the Growth Path of Federal Spending

The second component of transition financing assumed by the Social Security’s Chief Actuary in scoring the PPAP is a spending-limitation provision. The provision assumes a constant (20 percent of GDP) spending baseline, and then for eight straight years reduces by 1 percentage point the annual growth rate in spending required to maintain that constant share (which mathematically is equivalent to the annual rate of increase in nominal GDP). 48

The result would be to reduce federal spending from 20 percent to 18.5 percent of GDP by the end of the eighth year. For the next five years, spending would be held at a constant 18.5 percent of GDP by being allowed to increase at a rate equal to the nominal GDP growth rate. For the subsequent five years, spending would be allowed to grow as a share of GDP by increasing at a rate equal to the nominal GDP growth rate plus 1.75 percentage points.

Interestingly, according to the Congressional Budget Office, federal revenues have averaged 18.4 percent of GDP for the last 40 years, and revenues would continue to average 18.4 percent if the Bush tax cuts were made permanent and the AMT were indexed for inflation. Adopting this spending limitation provision and these two tax provisions not only would help finance the transition to large personal retirement accounts; doing so would balance the rest of the budget and “crowd out” other less important federal spending in order to meet the Social Security obligation. It is called “setting priorities.” And this approach provides the institutional mechanism to make those priorities stick.

The spending-growth-limitation provision scored by the Chief Actuary is far from draconian. Indeed, it just about matches the degree of spending restraint achieved by cooperating Clinton Democrats and Gingrich Republicans during the 1990s. The spending speed limit would lower the growth path of overall federal spending by slowing its growth rate about 1.5 percentage points a year from what CBO currently projects. By 2050, as illustrated in Figure 11, total federal spending (including transition funding) would be about 3.5 percent-of-GDP lower than currently projected — 29.3 percent vs. 32.8 percent — which is still 46 percent higher than today. Non-Social-Security spending (excluding transition funding) would be only 4 percent-of-GDP lower — 22.6 percent vs. 26.6 percent — which is still 13 percent higher than today.

Figure 11

Figure 11 depicts the long-run spending growth path under a spending growth-speed limit similar to the one proposed in the Ryan/Sununu bill. It illustrates just how mild the spending growth limitation is and clarifies the fact that the problem is not that huge spending cuts are required to finance the transition to large personal accounts (in fact it makes it easier since there are more savings to be devoted to Social Security under an accelerating spending baseline); the problem is that Congress would either have to raise taxes or borrow large sums on top of that required to finance the transition to large personal accounts in order to fund an exploding non-Social Security budget.

Looked at in this manner, it is not Social Security reform that poses the debt problem but rather a profligate Congress that insists on increasing the size of government outside all historic boundaries. Using the accelerating CBO spending baseline as an excuse to cut future Social Security benefits, whether under a reformed system or with the system as we know it, is the most craven of all political tricks.

It is understandable that proponents of big government detest the idea of using a spending limitation provision to help finance the transition to large personal retirement accounts. Not only does it remove a major vestige of socialism that keeps Americans dependent on government, it also effectively would pull the plug on interest-group liberalism that has fueled the constant growth of the welfare state for the past 75 years.

Under a spending limitation provision such as the one contained in PPAP, with every dollar in federal spending restraint being routed directly into personal retirement accounts, the incentives politicians face will be completely reordered. The politics of class envy and political class warfare will lose much of its attractiveness. Members of Congress and the president now would find it in their immediate political interests to finance personal accounts without raising taxes or cutting benefits: the nation of worker-owners would insist that the rate of federal spending growth be constrained so that savings could be devoted to financing personal accounts; voters would insist that the tax burden on saving, investment and entrepreneurial risk-taking be reduced; and the electorate would come to understand the true fiscal prudence of incurring a manageable public debt to effect the transition from the old welfare-state regime to the new investor-nation regime.

Economic Growth Effect of Spending-Restraint Provision

As alluded to above, the spending-growth-limitation would lower the growth path of overall federal spending by slowing its growth rate about 1.5 percentage points a year from what CBO currently projects. Figure 12 and Table 2 illustrate two very important consequences of achieving that modest amount of spending discipline. 49

Table 2

During the deficit years of the transition period (2005-2039), the “dis-saving” occurring as a result of government borrowing to finance the transition to personal accounts is more than offset by a decrease in government consumption produced by spending growth restraint, for a net increase in national savings of 5.7 percent. (See Table 2.)

Figure 12

Additionally, over the long term, surpluses emerge and all of the transition debt is paid off so that the net decrease in government consumption is twice the amount of transition borrowing.

There also would be second-order beneficial economic effects of adopting such a spending limitation provision. Based upon existing empirical research, it is possible to derive an order-of-magnitude estimate of the growth effects of reducing federal spending on the order of 1.5 percent of GDP in perpetuity. A 1999 NBER study found that:

- “Increases (reductions) of public spending reduce (increase) profits and, therefore, investment. The magnitude of these effects is substantial. A reduction by one percentage point in the ratio of primary spending over GDP leads to an increase in investment by 0.16 percentage points of GDP on impact, and a cumulative increase by 0.50 after two years and 0.80 percentage points of GDP after five years. The effect is particularly strong when the spending cut falls on government wages: in response to a cut in the public wage bill by 1 percent of GDP, the figures above become 0.51, 1.83 and 2.77 percent, respectively.” 50

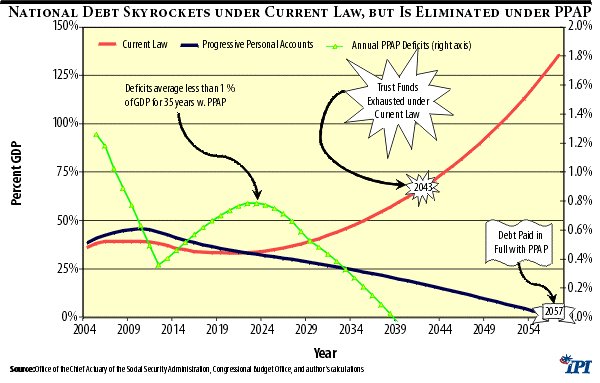

Figure 13 compares the public debt required to pay full Social Security benefits under current law without raising taxes to what the national debt would be under large progressive personal retirement accounts with the transition funding in place.

That comparison reveals that public debt, including accrued interest, rises by a total of $1.82 trillion (constant 2003 dollars) with large personal accounts. But the reform plan produces enough surpluses after 2028 to pay off all those bonds within the following 15 years, leaving the net impact on debt held by the public at zero over the 40-year time horizon. Continuing surpluses would permit the remaining payroll tax to be reduced from 6.0 percent to 3.5 percent by the end of the 75-year horizon. At no time would annual deficits exceed 1.5 percent of GDP, and they would average less than 1 percent most of the time.

Figure 13

Under the current system, Social Security will add $1.6 trillion (constant 2003 dollars) to federal debt held by the public by 2028, and rather than pay it off over the following 15 years would add an additional $8 trillion to the national debt by 2043. By 2057, when the entire national debt would be retired under PPAP, the insolvent Social Security system would have driven it to more than 125 percent of GDP.

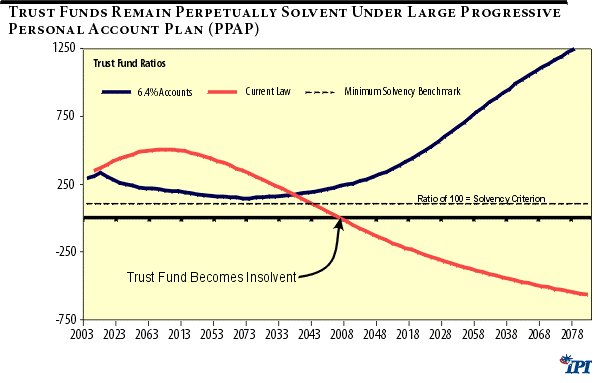

Long-Run Unfunded Liability of Social Security is Eliminated and Trust Funds Remain Perpetually Solvent

Figure 14 illustrates the fact that as the Chief Actuary scored the PPAP, the Social Security trust funds would never fall below $1.38 trillion, or 145 percent of one year’s expenditures (100 percent is the standard for solvency). After 2028, the trust funds would grow permanently, eventually reaching $6.3 trillion, or 12.5 times one year’s expenditures.

Figure 14

Under current law, the Social Security trust funds would start a permanent decline in 2018, and would be exhausted by 2042.

Sensitivity Analysis

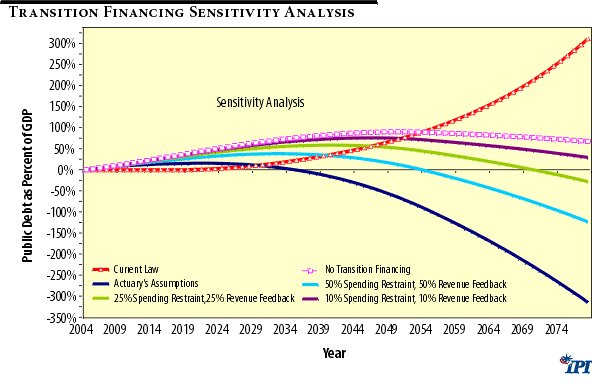

Figure 15 performs a sensitivity analysis to explore what happens under different assumptions about the degree of spending restraint and corporate revenue recapture.

Figure 15

The line labeled “Actuary’s Assumptions” reproduces the Chief Actuary’s assumptions on spending growth restraint and corporate revenue recapture. The line labeled “No Transition Financing” depicts what happens if there is absolutely no corporate revenue recapture (i.e., there is no increase to the nation’s capital stock as a result of the personal accounts) and if Congress refuses to restrain federal spending by so much as a dollar, in which case all of the transition financing must be borrowed. This is the extreme case that critics use to caricature the Progressive Personal Accounts Plan. As the foregoing analysis demonstrates, such a scenario is unlikely to occur.

The interesting characteristic of this extreme case, however, is how favorably it compares to the status quo. Public borrowing maxes out at 90 percent of GDP after 45 years and in the 50th year debt is exactly the same as it would be under current law — about 89 percent of GDP. During the next 25 years, debt as a share of GDP falls steadily to 69 percent under the worse-case scenario while it would explode to more than 300 percent of GDP under the current system.

But even this worst-case analysis does not eliminate the possibility that properly designed, a large-accounts reform combined with significant tax reform could finance the entire transition with debt. If federal spending restraint were combined with tax reform, the new borrowing required to debt finance the entire transition would be substantially less and perfectly manageable. (See “Who’s Afraid of the National Debt.” 51)

Figure 15 also illustrates that even if Congress is only one-fourth as effective restraining spending and recapturing corporate revenue as the limitation provides as Feldstein estimates, the debt remains perfectly manageable and is retired before the end of the 75-year actuarial horizon. While any long-range projection must be taken with a high degree of skepticism, Figure 15 lends confidence that the critics are mistaken who argue that large personal retirement accounts without future benefit cuts will blow a hole in the debt.

Moreover, deficit-hawks and debt-phobes ignore the political reality of the changed public-choice calculus that a reform like PPAP would produce. If Congress were to enact large personal accounts without future benefit cuts, and if it turned out that economic output did not rise as anticipated or Congress failed to restrain spending growth as instructed, workers would take intense political action to preserve their retirement accounts, and voters would exert intense political pressure on Congress to prevent debt from spiraling out of control.

In the unlikely event that this scenario came about and voters chose at that time, under those conditions, to raise taxes or scale back personal accounts in order to reduce deficits, so be it. That choice, however, is a decision for the democratic process to work out in the fullness of time, not for policy wonks to pre-determine.

Conclusion

A system of personal retirement accounts designed along the lines of the Progressive Personal Accounts Plan, including a built-in mechanism to control federal spending as part of the transition financing, would deliver unprecedented benefits to Americans. Not only would congressional budgeting be brought back under control, but the system would provide generous retirement security for workers, eliminate the long-run unfunded liability of Social Security, keep the trust funds perpetually solvent, boost economic growth, and ultimately pay off the national debt.

Policy makers and concerned citizens would do well to examine its merits and advocate its implementation.

Endnotes

- As with constitutional constraints on the war power, constitutional constraints on Congress’s taxing and spending authority have essentially withered away. Comedian Jon Stewart makes a profound point in a humorous manner: “Some scholars have argued [that] the Constitution clearly states only Congress can declare war, and they are not allowed to simply delegate that authority to the president. However, you can get around that with the legal technique of taking the word ‘constitution’ and adding the word ‘shmonstitution’ to the end of it.”

- “The Long-Term Budget Outlook,” Congressional Budget Office, December, 2003, Table 1-1, p. 7.

- 2003 Annual Report of the Board of Trustees of the Federal Old-Age and Survivors Insurance and Disability Insurance Trust Funds , March 17, 2003.

- See Testimony of Chairman Alan Greenspan, “Economic Outlook and Current Fiscal Issues,” before the Committee on the Budget, U.S. House of Representatives, February 25, 2004.

- Historical data and recent studies show that over the long run, bonds have yielded an average annual rate of return of 3.25 percent while stocks have generated a 7.25 percent rate of return. By comparison, workers born in 1960 are currently calculated to receive a real rate of return, on average, of less than 2 percent on their cumulative Social Security contributions. The situation only gets worse for workers born after 1960; for workers born after 1974, the average rate of return is negative.

- Ferrara, Peter, “A Progressive Proposal for Social Security Personal Accounts,” IPI Policy Report 176, June 13, 2003.

- See Hunter, Lawrence A. and Steve Conover, “Who’s Afraid of the National Debt? The Virtues of Borrowing as a Tool of National Greatness,” IPI Policy Report 159, July 2001.

- Ibid., p. i.

- The Economic Growth and Tax Relief Reconciliation Act of 2001 (EGTRRA) reduced marginal tax rates on individuals, increased and expanded the child tax credit, reduced tax rates on married couples, repealed the estate and gift tax, expanded individual retirement accounts, and made minimal changes to the AMT.The Jobs and Growth Tax Relief Reconciliation Act of 2003 (JGTRRA) accelerated the reductions in individual income tax rates enacted in 2001; accelerated marriage penalty relief; accelerated the increase in the child tax credit; increased section-179 expensing of plant and equipment; and eliminated the double taxation of corporate earnings by excluding corporate dividends received by shareholders from gross income and by allowing stockholders to increase the basis in their corporate stock to the extent the allowable dividends exclusion exceed the dividends paid by the corporation. Most of the tax cuts contained in these two pieces of legislation are scheduled to expire at the end of 2010; the rest expire even sooner.

- CBO describes the effect of making the Bush tax cuts permanent: “One approach [to tax policy] is to enact a series of legislative changes that would keep receipts close to their historical average share of GDP. That outcome could be achieved either through changes in the individual income tax system or through shifts among the various types of taxes. Consequently, the first [revenue] path is one in which receipts remain steady at 18.4 percent of GDP-the average of the past 30 years-beginning in 2012 ( see Figure 5-2). That percentage is the level that would result if the provisions of EGTRRA and JGTRRA were extended and the AMT were indexed for inflation beginning in 2005. See ”The Long-Term Budget Outlook," The Congressional Budget Office, Washington, DC, December 2003, Chapter 5.

- Most of the various tax cuts legislated in the Economic Growth and Tax Relief Reconciliation Act of 2001 (EGTRRA) and the Jobs and Growth Tax Relief Reconciliation Act of 2003 (JGTRRA) are scheduled to expire at the end of 2010; the rest expire even sooner.

- “Long-Term Budget Outlook,” op. cit., Chapter 5.

- If the Bush tax cuts are allowed to expire, CBO explains that “the tax code reverts to prior law, tax rates will rise, some credits will shrink, and thresholds for certain rates will shift. Those changes will increase the level of receipts as a share of GDP, both immediately and in the future.” Ibid., Chapter 5.

- Ibid., Supplemental Data." Retirees also find themselves adversely affected by the tendency of the current income tax to extract a larger share of income from individuals on Social Security. As CBO puts it, “Inflation and real wage growth would affect the threshold at which Social Security benefits became subject to taxation, because that threshold is not indexed. As a result, the proportion of total Social Security benefits that are taxed will rise from 19 percent today to 38 percent by 2050 .” (Emphasis added.) Ibid.

- In 1985, after Reagan budget director David Stockman retired from government, Sen. Moynihan reportedly said the budget director had told him privately that the administration’s plan was to have a “strategic deficit.” “That gives you an argument for cutting back programs that really weren’t desired and giving you an argument against establishing new programs you didn’t really want.”

- “Although there is some tendency over the long term for taxable wage and salary income to decline as a proportion of compensation, the overwhelming effect of the tax system’s current-law features is to raise receipts relative to GDP. Consequently, receipts rise to 24.7 percent of GDP by 2050 in the current-law path and are 6.3 percentage points higher than in the historical-average path.” See “Long-Term Budget Outlook,” op. cit., Chapter 5.

- Ibid.

- De Rugy, Veronique, “The Republican Spending Explosion,” Cato Institute Briefing Paper, January 23, 2004.