Introduction

The debate over fundamental tax reform necessarily embraces numerous questions concerning the economic and social viability of the various alternative proposals. At the core of the debate is whether a given proposal is more or less meritorious than the graduated income tax system presently in effect. What has not yet been thoroughly examined in the course of this debate is the question of whether and to what extent the present system is in keeping with the scheme of ordered liberty envisioned by our Founding Fathers.

It has been said that the genius of the Founders was their capacity to understand human nature and the nature of governments in general and then to strike a delicate balance between the interests of liberty on the one hand and the need for social order on the other. The Founders understood that a condition of absolute liberty necessarily implied social chaos or anarchy, while a government powerful enough to quash all discord was prone to abject tyranny.

As a result, the Founders created a Constitution under which specific powers were delegated from the people to the government. This concept, known as the doctrine of “enumerated powers,” recognizes that in their natural state, citizens enjoy unlimited rights but that in the course of social interaction, certain acts that operate to the detriment of others must be restrained. Government is the institution through which such restraint is imposed.

The new government under the Constitution was afforded only those powers necessary to protect the life, liberty and property of the citizens. At the same time, the government was expressly precluded from hindering citizens in the peaceful exercise of their basic liberties in the midst of industrial and social intercourse. Thomas Jefferson, the author of the Declaration of Independence, referred to these liberties as “inalienable rights,” or rights that are not subject to being bought, sold or transferred from one person to another or from a citizen to his government. Such rights are clearly expressed in the Constitution and the Bill of Rights.

Throughout history, there has been a well-documented and undeniable friction between the cause of liberty and the growth of government. Jefferson observed that the nature of things is for government to encroach upon liberty and for liberty to yield. In the context of the American experiment with liberty, nowhere has this friction been more apparent—and more detrimental to the interests of liberty—than in the area of taxation.

Former Chief Justice John Marshall observed that the “power to tax involves the power to destroy.”1 Such destruction manifests itself in many forms, including political, personal and economic. Even beyond these, the unchecked power to tax and enforce the collection of taxes has the direct, proximate result of dispossessing citizens of their otherwise inalienable rights.

The challenge for planners is to erect a system of taxation that allows the government to raise the revenue it needs for its legitimate functions, but to do so in a manner that is not offensive to the inalienable rights of the people. That is to say, the government must raise the revenue in the least invasive manner. To say it another way, government has an affirmative duty to respect the rights of the citizen while it undertakes to raise its needed revenue.

This study examines exactly how the current graduated income tax system has eroded—and in some instances eviscerated—certain inalienable rights. To erect a tax scheme that respects these rights we must: 1) understand how the current system offends them, and 2) make a conscious decision that as a society, it is necessary and desirable to limit the reach of government’s taxing power to the fullest extent possible. If we cannot agree upon the importance of the latter proposition, there is little reason to change the current system.

The Growth of the Income Tax Code: “It fills and disgraces our voluminous codes.”2

An objective examination of our current tax system leads to an inescapable conclusion: it is a mess. Since the inception of the income tax as we know it in 1913, the tax code has exploded to more than 18,000 pages of law and regulation. This says nothing of tens of thousands of pages of Revenue Rulings and Procedures issued by the IRS, nor the voluminous guidance papers issued by the Office of Chief Counsel, nor the hundreds of thousands of pages of court decisions that pour forth from the nation’s judiciary each year, all in an attempt to guide citizens and tax professionals through what all agree has become a hopeless quagmire of tax law.

The language of section 509(a)(4) provides a glimpse of exactly how complex and convoluted the code is. It reads in part,

For purposes of paragraph (3), an organization described in paragraph (2) shall be deemed to include an organization described in section 501(c)(4), (5), or (6) which would be described in paragraph (2) if it were an organization described in section 501(c)(3).

To illustrate the level of vicissitude that characterizes the code, consider this: during the decade of the 1980s alone, the code was changed more than one hundred times, including the massive Tax Reform Act of 1986. Moreover, between the three years 1996 to 1998, six major tax reform laws changed more than three thousand code sections and subsections. Since the 1986 Tax Reform Act amended the tax code from beginning to end, Congress saw fit to change the code seventy-eight different times.3 To make matters even worse, of the numerous changes made during the three years mentioned, eighty were made to apply retroactively and of those, twenty-seven were applied retroactively more than one year.4

The Effects of Tax Law Changes

The effects of these repeated and sweeping tax law changes are staggering, both for taxpayers and tax administrators. Taxpayers are expected to comply with the statutory morass under threat of additional tax assessments, penalties, interest, and in the worst case, criminal fines and imprisonment. To carry out enforcement of the code, the IRS has a potpourri of over 140 different penalty provisions it uses with increasing frequency. By contrast, the 1954 code contained just thirteen civil penalties.

The increasing incidence of penalty assessments is an excellent measure of tax code complexity. And while the IRS often points to tax penalties as a measure of non-compliance, such is certainly not the case with the overwhelming majority of citizens who struggle to comply with a code that grows more complex by the day.5 The fact is, most citizens do not cheat. Rather, they are tripped up by the code’s countless and often hidden traps. In this regard, former IRS Commissioner Shirley Peterson testified to Congress in 1992, saying,

The law is now so complex that it affects taxpayers’ ability to comply—and often affects their willingness to comply, as well…A good part of what we call non-compliance with the tax laws is caused by taxpayers’ lack of understanding of what is required in the first place.…Many taxpayers fail to comply because they are unaware of the requirements of the law or because they cannot easily understand what they are supposed to do.6

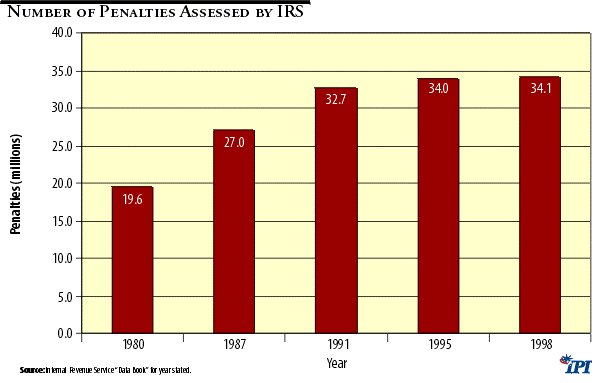

The following chart illustrates the growth of penalty assessments by the IRS over the past twenty years, during the period when Congress passed well over 150 tax law changes.

Chart 1

As more burdens are heaped upon citizens and businesses, it becomes increasingly difficult, and in some cases, impossible to assimilate and comply with the burdens. This leads to penalties.

Commissioner Peterson’s remarks are echoed by extrinsic evidence gathered today by the IRS’ Office of National Taxpayer Advocate (TA). The TA’s annual report to Congress describes the top twenty problems faced by taxpayers in complying with the code. The Taxpayer Advocate reports that both business and personal tax law complexity are the top problems faced by citizens. The FY 2000 report reads,

Complexity remains the number one problem facing taxpayers and is the root-cause of many of the other problems on the Top 20 List. Despite IRS restructuring to target services to taxpayer needs, the fact remains that the Internal Revenue Code is riddled with complexities that often defy explanation. 7

Consider the myriad of demands placed upon small businesses. This problem was recently addressed by the General Accounting Office. The findings were submitted to the Senate Small Business Committee on April 12, 1999, by Margaret T. Wrightson, the associate director, Tax Policy and Administration Issues, General Government Division of the GAO. Wrightson testified that small businesses are subject to multiple “layers of filing, reporting and deposit requirements” depending upon the nature of the business. She points out that,

By our count, there are more than 200 requirements—which we grouped into four layers—that may apply to small businesses as well as large businesses and other taxpayers.8

To be sure, not all 200 requirements apply to every business or individual taxpayer. However, it is equally true that the list of requirements imposed upon a given taxpayer is growing annually and so are the consequences for failure to do so.

Too Complex Even for the IRS

For help with compliance, taxpayers naturally turn to the IRS. To accommodate citizens, the IRS operates several taxpayer assistance programs designed to disseminate information and answer questions. The chief program is the IRS toll-free telephone assistance operation. During the 2000 filing season, the IRS received 79.6 million toll-free calls. More than 57 million of those calls were made during the months of January through June, the peak of the filing season. The number of calls was up from the 1999 filing season, when about 65.2 million calls were made.

What is more troubling than the increase in the number of calls for help, is the quality of help the IRS provides. According to the IRS’ annual measure of the accuracy of the information provided to taxpayers through this service, the agency answered 72.5 percent of taxpayers’ questions accurately in 1999. This is a drop of 10.7 percentage points from the 1998 figure. It means that 17.93 million citizens obtained incorrect information from the IRS in 1999.9

Why does IRS find it increasingly difficult to correctly answer taxpayers’ questions? Commissioner Rossotti addressed this very issue in a recent report on the IRS’ telephone assistance operation. His remarks illustrate better than anything else just how far the situation of tax law complexity has degenerated. These remarks, standing alone, should prove to even the most casual observer that the system in its present form is untenable. Commissioner Rossotti stated,

Fundamentally, we are attempting the impossible. We are expecting employees and our managers to be trained in areas that are far too broad to ever succeed, and our manuals and training courses are, therefore, unmanageable in scope and complexity.10

Very simply, Commissioner Rossotti conceded that the job of providing accurate information cannot be done given the scope, breadth and complexity of the current tax code.

This also explains why tax auditors themselves (IRS employees actively engaged in the task of ascertaining the correctness of tax returns) cannot keep up with the ever-changing and increasingly complex code. In 1994, Lynda D. Willis of the General Accounting Office testified before the House subcommittee on IRS Oversight regarding compliance problems faced by businesses. Ms. Willis explained,

The complexity of the code has a direct impact on IRS’ ability to administer the code. The volume and complexity of information in the code make it difficult for IRS to ensure that its tax auditors are knowledgeable about the tax code and that their knowledge is current.11

This is one reason why IRS’ tax audit results are wrong between 60 and 90 percent of the time.12

The law is now so complex that the typical citizen and small business owner are no longer comfortable going it alone. In growing numbers, these taxpayers are turning to paid preparers—tax professionals—for help complying with the law. In 1981, just 41 percent of taxpayers used paid professionals. Today, the number is in excess of 50 percent and it is estimated that as many as “94 percent of small business owners used a paid preparer or accountant to prepare their 1998 tax return.” The reason given was “ complexity.”13

The sad reality is that tax professionals suffer from the same frustrations as everybody else when it comes to deciphering the code. Too often, the efforts of paid professionals to navigate the swirling waters of the tax code are just as futile. The blizzard of reform legislation and tax litigation makes it functionally impossible for any one person to stay on top of every element of the law.

This fact is evidenced by Money Magazine’s annual study of tax law complexity. The study began in 1987, one year after the 1986 Tax Reform Act “simplified” the code. In the study, Money constructs a hypothetical family financial profile based upon the demographics of its readers. The facts are presented to fifty different private sector tax professionals with this simple instruction: compute the tax liability of the sample family based upon your understanding of the tax code and facts given.

In each of the surveys from 1987 to 1991, fifty different tax preparers came up with fifty different answers. What is worse, none calculated the correct answer. The results of the 1992 study were the same, except that two preparers dropped out before the study was complete. In commenting on the fact that no preparer hit the target tax, Money editors stated that, “While there were no perfect scores, a dozen returns were exemplary. Because of the tax code’s ambiguity, the target tax of $26,619 was not the only acceptable answer.”14

It is this kind of ambiguity that leads to inconsistent and sometimes arbitrary law enforcement and substantially drives up the cost of the compliance with the code.

The Constitution and Ambiguous Law

One of the fundamental rules of constitutional law is that citizens have a right to know in advance what acts are proscribed or required by law. This premise grows from the Fifth Amendment’s guarantee that no person shall be “deprived of life, liberty or property, without due process of law… ”

When a law imposes sanctions for its violation, the due process clause is offended where the statute in question is so vague that a reasonable person cannot understand that his contemplated conduct is proscribed. This concept is known as the “void for vagueness” doctrine and generally applies to criminal statutes containing penalties for proscribed behavior.

The tax code contains more than 140 penalty sanctions, both criminal and civil in nature. Both the criminal and civil sanctions apply to the accuracy of tax returns and the manner in which a taxpayer treats a given transaction. Every time a tax return is filed, a citizen exposes himself to potential law enforcement action associated with that return. Yet, all are agreed that it is virtually impossible to fully comply with the code or to understand its full import. As illustrated above, not even the IRS or paid tax professionals understand the code’s scope or breadth. It is an assault upon the doctrine of fundamental fairness to hold common citizens accountable to a law that nobody can understand.

The Supreme Court, in the case of Connally v. General Construction Co. , stated it this way:

[A] statute which either forbids or requires the doing of an act in terms so vague that men of common intelligence must necessarily guess at its meaning and differ as to its application, violates the first essential of due process of law.15

Congress owes our citizens and businesses a stable and understandable tax code. More than any other area of law, the tax law touches and affects every American by imposing a growing list of affirmative duties. Given the sweep of this law, the Fifth Amendment’s guarantee of due process mandates a simple, stable tax code that is capable of being followed from year to year. Such a code would allow both individuals and businesses to plan their financial affairs with confidence and certainty from one year to the next. A stable and understandable tax code is in keeping with the first object of good government, to protect the property of its citizens.

In Federalist No. 62, Madison spoke of the importance of stability in the legislative process. He likened legislative instability to an individual without a plan to “carry on his affairs.” He noted that such a person is marked “as a speedy victim to his own unsteadiness and folly.” Madison described in detail the negative effects that a “mutable” legislative policy has on the internal affairs of a nation. He wrote,

It poisons the blessing of liberty itself. It will be of little avail to the people that the laws are made by men of their own choice, if the laws be so voluminous that they cannot be read, or so incoherent that they cannot be understood; if they be repealed or revised before they are promulgated, or undergo such incessant changes that no man, who knows what the law is today, can guess what it will be tomorrow. Law is defined as a rule of action; but how can that be a rule which is little known and less fixed?

Madison pointed to the condition of America’s legal system at the time of his writing. He observed,

What indeed are all the repealing, explaining, and amending laws, which fill and disgrace our voluminous codes, but so many monuments of deficient wisdom; so many impeachments exhibited by each succeeding against each preceding session; so many admonitions to the people of the value of those aids which may be expected from a well-constituted senate?

Madison might have been referring to our current tax code, as it is indeed a “monument of deficient wisdom,” lacking order, stability, simplicity and consistency.

The Reason Tax Laws are Complicated: “Congress shall have the power to collect taxes to provide for the general welfare of the United States.”

Reasonable people naturally ask, “Why can’t the tax laws be more simple?” The answer is they can be. The reason they are not is that Congress uses the tax laws for reasons other than that for which they were intended. Misuse of the tax laws accounts for the complexity of the system.

As early as 1969, well before we witnessed the explosion in the size, scope and complexity of the code, certain members of Congress voiced concerns about the direction of the law. Sensitive to growing concerns over tax law complexity even then, former Oklahoma Senator Henry Bellmon testified before the Senate Finance Committee as follows:

I believe the main purpose of our tax system should be to raise revenue. During the period of the 1930s, the idea of using our revenue-raising laws to accomplish certain social aims has complicated and caused great confusion in the administration of these laws.With the passage of vast quantities of social legislation in other fields, with the increased socially oriented activities of the United States Supreme Court, and with the creation of many additional federal programs to deal with social problems, it occurs to me that any tax reform legislation passed by the present Congress might will take note of the fact that the need for using our tax system for social purposes may no longer require the same high priority.

If this concept could be adopted, the law can be vastly simplified. It can be much more easily understood and followed by individual taxpayers, and it can be much more effectively enforced by those who are charged with its administration.16

What Bellmon observed as the reason for complexity in the 1960s continues to be the reason the tax law is such a mess today. This is confirmed by the IRS Commissioner in his Annual Report to Congress on tax law complexity. In the 2000 report, the Commissioner notes,

Complexity is frequently introduced as policymakers make trade-offs between simple tax designs and the desire to make the tax system fair and equitable in a fashion that supports social and economic as well as tax policy goals. 17

For more than fifty years, Congress has used the graduated income tax system as a means of enforcing the now transient notion of “social justice.” Rather than simply raising revenue, the tax laws are used to modify behavior by rewarding certain conduct perceived by current policymakers as desirable and penalizing other conduct perceived as undesirable for purely social reasons.

Examples of this abound, but perhaps the best is found in the 1993 budget proposal of former President Clinton. The former president was in his first term of office after being elected on the promise of cutting taxes for the middle class and raising them on the richest Americans. His reasoning was to equalize what he perceived to be the “uneven prosperity of the last decade.”18 To accomplish this, his plan imposed a $326 billion tax hike, the largest single tax increase in American history.

This is an illegitimate use of Congress’ taxing power. Our Founders imparted taxing authority to the federal government for the sole purpose of allowing it to raise revenue to fund its legitimate, clearly defined constitutional functions. It has no authority to use its taxing powers for any other reason, including the achievement of social ends.

Congress’ legitimate power to tax derives from Article I, section 8 of the Constitution. The power to tax, like all powers delegated to the federal government under the Constitution, is limited. The section reads, in relevant part,

The Congress shall have Power To lay and collect Taxes, Duties, Imposts and Excises, to pay the Debts and provide for the common Defense and general Welfare of the United States.19

Thus, the taxing power is narrowly applied to just three categories: (1) paying the debts of the nation, (2) providing a national defense, and (3) ensuring the general welfare (read, “soundness”) of the United States. There exists, neither in this clause nor any other in the Constitution, a power to employ Congress’ taxing authority for social purposes.

The Founders never intended such a power to exist for one simple, very logical reason. The social agenda of the nation is subject to change with each change of power in Washington. Each faction has its own idea of how things should be. Each individual election at every level represents, at least ideologically, a shift in power. If each faction were allowed to use the public’s standard of living as the means of affecting its social agenda, citizens are deprived of their most basic rights guaranteed by the Constitution. They are deprived of their property and the pursuit of happiness so that others may impose their notions of social justice upon them without their consent.

The idea of using the power of taxation to accomplish purely social goals was espoused by Karl Marx. The Marxist philosophy of socialism was designed to create an all-powerful state and to eliminate individual property rights. As we know from experience in eastern Europe and the former Soviet Union, socialism does not work. With all incentive to produce removed from their economies, Soviet nations and their satellites simply stagnated. All citizens but the ruling class were reduced to abject poverty with no hope of bettering their conditions.

In Marx’s Manifesto, he described the process of achieving the destruction of individual property rights. He writes,

The proletariat [defined by Marx as the “wage-labor working class”] will use its political supremacy to wrest, by degrees, all capital from the bourgeois [defined as “middle-class property owners”]; to centralize all instruments of production in the hands of the State, i.e., of the proletariat organized as the ruling class; and to increase the total of productive forces as rapidly as possible. Of course, in the beginning this cannot be affected except by means of despotic inroads on the rights of property, and on the conditions of bourgeois production…20

To achieve the state-enforced transfer of wealth he envisioned, Marx developed a ten-point plan to impose in “advanced countries” through the process of legislation. Points two and three read,

2. A heavy progressive or graduated income tax.3. Abolition of all right of inheritance.21

The concept of transferring wealth (or denying the right to transfer wealth as through an estate tax) to impose a social agenda is an idea repugnant to the Constitution and our system of limited government. To solve America’s fiscal problems, we must therefore abandon this practice in favor of a politically and socially neutral system of taxation. To satisfy the financial needs of the nation and remain true to our heritage, our tax system must not favor particular industries, factions or individuals at the expense of others. It must not fall more or less heavily upon one faction or industry solely because of its social standing.

Taxation to Provide for the “General Welfare”

The Constitution’s taxing authority to “pay the debts” of the nation and to provide for its “defense” seem clear enough. But what of the power to provide for the “general welfare?” This clause is the source of great misunderstanding. Its meaning has been debated from the outset.

It might seem that the “general welfare” clause of Article I, section 8, imparts broad authority on Congress to enact funding measures that it alone deems appropriate. Indeed, does not the use of the phrase “general welfare” itself grant license to utilize taxing powers to achieve social goals? After all, is not “welfare” the quintessential social undertaking? This certainly is the contemporary interpretation. However, to ascertain the true meaning of the term, we must visit the opinions of those who wrote the Constitution.

The term “welfare” as used today implies all manner of programs designed to uplift the poor, the disabled, the uneducated, the orphaned or widowed, and those harmed by natural disasters or other economic conditions. Such programs are responsible for hundreds of billions annually in government spending.

However, if the Founders intended to allow government spending for such programs, they would not have used the term “welfare” to describe them. In his singular essay entitled, “The General Welfare,” noted historian and constitutional scholar Clarence B. Carson observes that,

What Americans began calling welfare programs in the late 1930s, or thereabouts, the Founders would have known by the name of “poor relief,” so far as they were familiar with it at all. 22

At length, Hamilton and Madison addressed the taxing power under the “ general welfare” clause of Article I, section 8.

Madison expressed what today might be termed the “conservative” viewpoint. He reasoned that since the specific powers of the federal legislature were limited to but six narrow areas, the taxing power of Article I, section 8 could be no broader. Congress has the power to raise an army and provide a common defense. It is empowered to maintain domestic tranquility and facilitate intercourse among the several states and with foreign governments. Certain utilitarian functions are imparted to the national legislature, such as the maintenance of post offices and post roads. Madison affirmed that the federal government enjoyed no power that was not expressly delegated under the Constitution. It therefore could not use its taxing authority for anything other than effecting the clear and limited purposes of the Constitution.

During the public debate, some claimed that Article I, section 8 imparted unlimited taxing powers to the federal government because of the undefined “general welfare” clause. Madison retorted, “No stronger proof could be given of the distress under which these writers labour for objections, than to their stooping to such a misconception.” He explained there is no authority for Congress to rely upon the “general welfare” expression to expand its taxing power, if in so doing, it disregarded “the specifications which ascertain and limit” its authority.23

Hamilton, on the other hand, asserted what we would today refer to as a more “liberal” view of the Constitution’s taxing authority. Like all our Founding Fathers, he recognized the powers imparted to the new government were limited, but clearly aspired to create a more proactive federal government. In Federalist No. 34, he explained the taxing power was “indefinite.” He viewed the clause as imparting to Congress “the discretion to pronounce” the objects of taxation which “concern the general welfare.”24

Despite the divergence of opinion of the two authors on the topic, both were in agreement that the power of taxation did not involve the power to redistribute wealth. The “general welfare” clause does not grant license to establish a welfare state under which largess is distributed to one class of citizens at the expense of another. Even in Hamilton’s liberal view of matters, he cautioned,

The only qualification of the generality of the phrase in question, which seems to be admissible, is this: That the object of which an appropriation of money is to be made be general, and not local; its operation extending in fact or by possibility throughout the Union, and not being confined to a particular spot. 25

If it is true that appropriations must be general in nature, not confined to “a particular spot,” it must logically follow that programs benefiting only selected groups or classes of citizens cannot possibly meet the constitutional test of relating to the nation’s “general welfare.”

If Madison represented the more conservative view, and Hamilton the more liberal view, then Jefferson likely expressed the balanced view. He sheds further light upon the issue, remarking,

The laying of taxes is the power, and the general welfare is the purpose for which the power is to be exercised. They [Congress] are not to lay taxes ad libitum [defined, “at pleasure”] for any purpose they please; but only to pay the debts or provide for the welfare of the Union. In like manner, they are not to do anything they please to provide for the general welfare, but only to lay taxes for that purpose.26

These remarks indicate that taxation and government spending is intended for the welfare of the nation as a whole, not its individual inhabitants or locales, and certainly not individual classes of citizens or industries. The authority to tax exists only to further the greater concerns of the Union itself. We must therefore conclude that the power to provide for the “general welfare” does not authorize distributions from the treasury to the benefit of private interests, individual concerns, or purely local pursuits. More importantly, there exists no authority to employ the power to tax as a means to correct perceived social or economic injustice.

Taxation under our Constitution, even from the liberal view, was never designed to favor one business over another or one property interest over another. Taxation is nothing more than the simple expedient of raising money for the operation of the legitimate functions of government.

Professor Carson concludes his essay by writing,

In sum, then, it is most unlikely that the makers of the Constitution would have chosen the phrase, “general welfare,” to authorize the federal government to provide what they understood to be poor relief. It would have violated both their understanding of the meaning of the words and the common practice as to what level of government should provide the relief. On the contrary, it appears that relief came to be called welfare to give it a semblance of constitutionality. Indeed, close analysis within the sentence and the context of the Constitution points to the conclusion that the reference “to provide for the general welfare” was the restriction of the taxing power rather than a separate grant of power.27

In 1936, the Supreme Court visited this very question in the case of United States v. Butler, wherein the court considered the constitutionality of an excise tax imposed by the Agricultural Adjustment Act, passed in 1933. The stated purpose of the act was to correct an “economic emergency [that] has arisen, due to disparity between the prices of agricultural and other commodities, with consequent destruction of farmers’ purchasing power.”28 The act imposed excise taxes upon processors of commodities as specified in the act. The proceeds were to be used, among other things, to pay farmers to take acreage out of production, thus increasing the price of certain commodities by reducing their supply. There was clearly a social agenda behind the tax. Its constitutionality was challenged by Butler, a processor against whom the tax was levied.

In its decision holding the act unconstitutional, the Supreme Court struck at the core of what today has become habitual congressional action; that is, using the power to tax under Article I, section 8 as a means of imparting special benefits to certain classes of society or rewarding those who behave in a “ ;socially acceptable” manner. The Supreme Court stated,

A tax, in the general understanding of the term, and as used in the Constitution, signifies an exaction for the support of the government. The word has never been thought to connote the expropriation of money from one group for the benefit of another.29

Drawing upon the historical writings surrounding the clause in question, the court determined that congressional expenditures must be consistent with the specific powers delegated to Congress in the Constitution. To hold otherwise would be to suggest that Congress could do anything it wants under the authority of the taxing clause. In the words of the Supreme Court, such a conclusion would transform the United States “into a central government exercising uncontrolled police power in every state of the Union.”30

Because there is no specific authority in the Constitution for Congress to regulate the price of agricultural commodities, any such expenditure (and a plan of taxing to raise revenue to support them) must be unconstitutional.

Jefferson spoke plainly about the effects of using the taxing power to carry out transfer payments for social purposes. He said,

To take from one, because it is thought his own industry and that of his father has acquired too much, in order to spare to others who (or whose fathers) have not exercised equal industry and skill, is to violate arbitrarily the first principle of association, “the guarantee to everyone a free exercise of his industry and the fruits acquired by it.” 31

Whether politically conservative or liberal, our Founders shared a common goal. As seen from the juxtaposition of Madison and Hamilton, they may have approached it differently, but their purpose was the same. Each possessed a burning desire to establish and ensure the greatest measure of individual liberty possible. They recognized that unlimited taxing power is a direct threat to liberty. Therefore, to restore sanity to the tax code itself, we must restore Congress to the constitutional limits of its taxing authority.

The Core Principle of the American Experiment: “All men are created equal.”

Abraham Lincoln referred to the equality clause of the Declaration of Independence as the “gem of liberty.” Because “all men are created equal,” and therefore stand equal before the law, all have an equal opportunity to pursue, use and enjoy their own labor and the fruits thereof. The proposition that liberty demands equality is drawn from John Locke, the seventeenth century English jurist whose writings shaped a preponderance of the thinking of our Founders. In his classic essay, “ Concerning Civil Government,” Locke declares that the “freedom of men under civil government is to have a standing rule to live by, common to every one of that society, and made by the legislative power erected in it.” 32

From the teachings of Locke and others like him, the Founders fashioned Article IV, section 2 of the Constitution. It reads, “The citizens of each State shall be entitled to all the privileges and immunities of the citizens of the several States.”

This is the so-called “equal protection” clause of the Constitution. Its intention is to ensure that all citizens are treated equally by the law and that no special favor or grant of privilege is extended to one class of citizens at the expense of another by mere virtue of their social or economic standing.

Of course, in the early years of the Republic, there was a great scourge in America—slavery. By the 1850s, the debate raged as to whether African slaves enjoyed the same rights as any other American. The contest over the States’ right to permit slavery led to the Civil War, after which the Fourteenth Amendment was promulgated. Section 1, clause 2 of the Fourteenth Amendment reads much the same as Article IV, section 2, but also encompasses elements of the Fifth Amendment. Section 1, clause 2 of the Fourteenth Amendment provides that,

No State shall make or enforce any law which shall abridge the privileges or immunities of citizens of the United States; nor shall any State deprive any person of life, liberty or property, without due process of law; nor deny to any person within its jurisdiction the equal protection of the laws.

Since the Constitution and its amendments were plain limits on the national government and not the state governments, the consequence of the Fourteenth Amendment was to allow the national government to enforce upon the states the promises of liberty for all citizens. The Civil Rights Bill of 1866, introduced by Senator Lyman Trumball of Illinois, birthed the Fourteenth Amendment. In bringing the idea before Congress, Trumball stated,

Good faith requires the security of the freedmen in their liberty and their property, their right to labor and their right to claim the just return of their labor. Monopolies, perpetuities and class legislation are contrary to the genius of free government, and ought not to be allowed. Here there is no room for favored classes or monopolies; the principle of our Government is that of equal laws and freedom of industry. Wherever monopoly attains a foothold, it is sure to be a source of danger, discord and trouble. We shall but fulfill our duties as legislators by according “equal and exact justice to all men,” special privileges to none.33

In this premise lies the core principle of American government. All men are created equal. No man ought to enjoy a standing before the law that imparts special privilege or advantage over that of his neighbor. For, as Thomas Paine observed, “the riots and tumults” that occur from time to time are more often occasioned by government itself, because “instead of consolidating society, it divided it; it deprived it of its natural cohesion.” According to Paine, the chief culprits in this regard are “ ;excess and inequality of taxation,” through which the great mass of society is “thrown thereby into poverty and discontents.”34

Yet despite these teachings, our current tax code is replete with examples of unfair and unequal treatment, the result of which is not only a confusing code but one wherein otherwise similarly situated citizens are treated differently under the law. Nothing has changed in the nature of man since the time of Paine’s writings because even today, one of the chief sources of social frustration is the idea that our tax law and its burdens are unfair.

In 1990, the IRS visited the question of the public’s perception of tax law fairness. The question was posed specifically in light of the Tax Reform Act of 1986, which was marketed to the public as a massive tax simplification measure intended to level the playing field. Regardless of what the ’86 act in fact accomplished, the IRS’ study found that “most people feel the tax system is less fair now that it was before tax reform.”35 Citing surveys back to 1977, the IRS observed,

Consistently, surveys show that the majority, (about 60 percent), feel the tax system is either somewhat unfair or quite unfair. Initially, the 1986 Tax Reform Act appears to have improved people’s perception of the tax system’s fairness. In 1987, about as many people (roughly 45 percent) felt the tax system was fair as unfair. However, as illustrated in Figure 4 [not reproduced here] recent surveys show that these percentages have returned to pre-tax reform levels, suggesting that these perceptions are a result of widespread public skepticism and a dissatisfaction with the tax system in general.36

While that 1990 study is the latest produced by the IRS, a more recent study by Reader’s Digest, pointed more at the tax burden itself, confirmed the IRS’ own finding. The poll asked respondents a number of questions regarding the fairness of the tax they pay. The findings reveal “astounding unanimity,” “ remarkable consensus” and “broad dissatisfaction” among Americans with the amount of tax paid:

Self-described conservatives agreed with self-described liberals. Singles agreed with marrieds. Blacks agreed with whites. Americans in nearly every group—across racial, economic, age, ideological, religious, educational and sexual lines—had the same median response…37

The response was that the tax system is unfair.

The following discussion addresses just a few examples of the inequities in the system.

The graduated income tax rates— The graduated rates guarantee that citizens are treated differently under the law based solely upon their economic or social standing and nothing else. Our current system sports six different tax rates, beginning with a 10 percent bracket and progressing to a 38.6 percent bracket for the highest income earners. The establishment of these brackets is based upon nothing other than the socialist proposition that those who earn more income should pay a greater percentage of that income in taxes. The Clinton Administration expressed this sentiment clearly in its 1993 call to increase the top tax bracket from 31 ;percent to 39.6 percent.38 Speaking of what was then a proposed increase, the White House stated,

It will require those who have profited to bear the greatest burdens and do right by the people who work hard and play by the rules.39

The chief problem with graduated tax rates is that they are arbitrary. They are not based upon any sound legal or economic principle, only that those who make more should pay more. This is evidenced by the wild fluctuation in the brackets since the inception of the modern income tax in 1913. When the income tax as we know it was adopted, the bottom tax bracket was 1 percent of income over $20,000 and the top bracket was just 6 percent and applied to incomes in excess of $500,000 (the “super-rich” when measured in today’s dollar).

Even before the first income tax law was birthed, it was apparent to legislators that the rates and brackets would be arbitrary. While debating the 1913 Income Tax Act, North Dakota Senator Porter J. McCumber declared,

Mr. President, it is quite evident that no two Senators will agree upon the number of steps [tax brackets] in the sliding scale in this bill, and it is equally clear that no two of them will agree upon the ratio of rate for each particular step.40

Since that time, and beginning in earnest in the 1940s, America has been subjected to an increasing number of tax brackets and a growing percentage of their incomes goes to government at all levels. The cry of those who would raise progressive rates is always based upon the concept of invidious discrimination; that is, the notion that it is somehow “unfair” that some among us earn more than others and that the masses of middle income citizens can “get even” with those better off by raising their taxes.

Of course, it is functionally impossible to define “fairness” when it comes to graduated tax rates. Why, for example, is it “fair” for one person to pay at a 27 percent rate while another should pay at the 38.6 percent rate? Both the rates of tax and the levels of income at which those rates apply are arrived at in a purely arbitrary and subjective manner. On this basis, why is it not fair for the person paying 38.6 percent to pay at 50 percent? In fact, if 38.6 percent is “fair” for high-income earners, is not 50 percent even “more fair?” And if 50 percent is more fair then 38.9 percent, where is the point at which the highest bracket becomes “unfair?” As any reasonable person must agree, these questions have no answers. As a consequence, the notion of a graduated income tax is therefore, fundamentally unfair.

One illustration of the absurdity of the progressive rates lies with the history of the highest tax bracket. This bracket exists as a result of a 10 percent surtax imposed in 1993 on what was then the highest tax bracket of 36 percent. The surtax was dubbed the “millionaire’s tax.” However, when it took effect, it applied to taxable incomes of $250,000 or more—not $1 million.41

As demonstrated in the above discussion, the historic ideals of due process and equal protection mandate that citizens be treated equally as they stand before the law. The lack of objective guidelines upon which to base graduated tax rates renders them fundamentally flawed from a constitutional perspective. What is “fair” in one year is suddenly “unfair” as soon as the power base in Congress shifts. This fact has kept tax rates on a roller coaster for over five decades.

America’s frustration with graduated income tax rates manifested itself in the past several years in the form of a debate over the so-called marriage penalty. The marriage penalty operates to increase the amount of tax paid by a married couple over that which they would have paid on the same income if they stayed single. The debate betrays a fundamental misunderstanding of why the so-called marriage penalty exists in the first place. Whatever else may be said, the marriage penalty is inextricably intertwined in the graduated income tax system itself. Let me illustrate.

Suppose two single people each earn $26,000 per year taxable income. Based upon the 2000 income tax rates and brackets, that income is taxed at the 15 percent rate and consequently, each would pay $3,904 in income tax. The total tax paid by both citizens is $7,808. When these people marry and file a joint return, they combine their respective incomes. As a result, their total taxable income is $52,000. However, this income is no longer taxed exclusively at the 15 percent rate. Taxable income in excess of $43,850 is taxed at the 28 percent bracket. As a result, the total income tax liability for these same people earning the same money is $8,867—$1,059 more than they paid as single people.42

The graduated income tax rates impose greater burdens on certain elements of society merely as a result of their social standing.

Tax return filing status —The code provides for five different filing status classifications. They are,

- Single

- Married filing jointly (even though only one spouse has income)

- Married filing separately

- Head of Household

- Surviving Spouse

Each of these separate classifications ensures preferential treatment to different classes of citizens based solely upon their social standing. Like the graduated tax rates, the filing status classifications are arbitrary and not subject to any objective standard of law or economics. They are subject to change at the whim of the legislature and have the direct effect of imposing unequal burdens upon citizens who might otherwise be equal in the economic standing.

For example, a married person filing a joint income tax return for 2000 paid at the 15 percent rate on the first $45,200 of taxable income even if the income on the joint return was earned by just one spouse. However, for a single person, the 15 percent rate ceased to apply at $27,500. The income of the single person in excess of $27,500 was taxed at the 28 percent level. So merely because he is not married, the single person paid substantially more than a married person, even though the latter, like the former, may be the sole income-earner and have no children to support.

On the other hand, a single person with dependent children (head of household) was taxed at 15 percent on the first $36,250 of taxable income. This is true even though he has children to support while the married couple may not. Depending upon the number of children involved, the dependent exemptions for those children are not likely to level the playing field between the married person with one income and the single head of household with dependents.

If a married person filed a separate return to report his own income, the 15 percent rate ceased to apply at $22,600 of taxable income. Thus, the tax on $45,000 of taxable income at the married filing separately rate was $9,662, while the tax on the same income at the married filing jointly rate was $6,750, a difference of $2,912. This was true even if the married filing jointly income was earned by just one spouse.

Including the so-called marriage penalty and the filing status classifications discussed here, there are a total of fifty-nine provisions of the tax code where tax liability depends, in whole or in part, upon the question of whether an individual is married or single. In its 1996 study of the matter, the GAO reported the following:

The different ways that married and single people are treated under the income tax code could lead to situations where the tax liability of married taxpayers is not the same as that of two similarly situated single taxpayers.43

The disparate treatment accomplishes nothing other than to polarize citizens within their various social groups and ensure that each group is treated differently based upon their social status. These contradictions grow directly from the use of the taxing power of the United States as a means of arbitrarily grafting federal social policy into our tax laws. The first casualty in such a process is the doctrine of equality before the tax law.

For example, the growing awareness that single parent households were the primary source of children in poverty is chiefly what led to targeted welfare entitlements to that group, as well as the expansion of the 15 percent tax bracket and the exemption for a preferential “head of household” filing status. However, while that filing status affords preferential treatment to unwed mothers, it is in fact inequitable to married families with children—especially those also living in poverty. Moreover, that filing status effectively operates as a tax subsidy for unwed motherhood, which when considered with other welfare subsidies, contributes to the growth in the number of unwed mothers.

In the same way, in 1969 social planners seeking to eliminate the perceived benefits of marriage under the tax code restructured brackets and exemptions for married couples. Previously, such brackets and exemptions were double those of single persons. By replacing them with narrower marital brackets and a lesser personal exemption, the new structure now clearly discriminates against two-income married families. Moreover, it also effectively discriminates against single income marriages as the only legal partnership not allowed to split income. As a consequence, an increasing number of cohabitating couples, either with or without children, deliberately avoid or conceal marriage.

The Alternative Minimum Tax— The Alternative Minimum Tax (AMT) is a secondary tax system that runs alongside the “regular” tax system. Established in 1978, the AMT was initially intended to ensure that high-income taxpayers pay some tax even if allowable deductions, credits, etc., substantially reduced or eliminated their “ regular” liability. AMT rates and tables are entirely different than those that apply to the regular income system. The AMT is, in essence, a flat tax system that operates coterminously with the graduated tax system. In application, the AMT guarantees that certain classes of taxpayers do not enjoy the same deductions, credits and exemptions as others similarly situated.

The AMT is an admission by Congress that the system in its present form is fundamentally unsound and inequitable. After realizing that certain taxpayers could substantially reduce or eliminate their tax liability using tax exemptions and deductions expressly provided for within the code, Congress decided that it should erect a safety net to ensure that everybody paid some taxes, even those otherwise entitled to legal deductions and exemptions. That safety net is the AMT. But as the National Commission on Restructuring the IRS observed in its report to Congress, “If the tax base was designed to be truly fair and comprehensive, there would be no need for a minimum tax.” 44

In the first place, the AMT is horrifically complicated. It was referred to by the IRS itself as “intricate and ambiguous.”45 It has been changed fourteen times since originally enacted. The AMT requires that certain taxpayers calculate their tax liability using two differing sets of rules and procedures, one under the normal income rules and the other under the AMT rules. Consider this description from the Commissioner’s Annual Report on Tax Law Complexity:

If married filing separately taxpayers think they are subject to AMT and follow all the procedures, they could end up calculating four different tax outcomes—regular tax filing jointly and separately and AMT filing jointly and separately. Publication 17 recommends that all married taxpayers calculate their tax liabilities filing jointly and separately to minimize their tax liability. As a result, a married taxpayer could conceivably have to make six sets of calculations to determine the actual taxes owed, including the exemption surtax.46

It is chiefly for this reason that the National Taxpayer Advocate recommended to Congress on at least two occasions that the AMT be “eliminated” as its “first choice” among several reform alternatives.47

The law requires a citizen to pay the higher of the normal income tax or the AMT. In calculating the AMT, the taxpayer must add back to income various items the AMT describes as “preferences” and “adjustments.” These include but are not limited to the standard deduction, dependent exemptions, miscellaneous itemized deductions, some mortgage interest, a portion of medical expense deductions, real estate and personal property tax deductions, etc.48

In this way, the AMT virtually ensures that not all citizens are treated equally under the law. By its very nature and inherent structure, the AMT deprives certain taxpayers of otherwise perfectly legal deductions, credits, exemptions, etc., that other similarly situated taxpayers may claim. By operating this system, Congress capriciously offers deductions with one hand then withdraws them with the other. Even worse, many citizens are not even aware of the AMT or the increased tax liability it imposes until they are so notified by the IRS.

The conflicting definitions of the term “child”— The tax code contains six definitions of the term “child,” each applying to different elements of the code. The six definitions apply to the head of household filing status, dependent exemptions, the Hope and education tax credits, child and dependent care credits, the Earned Income Tax credit and the general child credit.49

In each of the code sections in question, Congress uses various fact tests to determine whether a child meets the definition offered by Congress. If so, the child’s parents may claim the particular benefit on their tax return. Within the six definitions of the term “child,” there is a combination of up to five different fact tests that must be met in order to comply with the rule. These fact tests are,

- The relationship or member of household test;

- The support test;

- The residency or keeping up a home test;

- The age test; and

- The income test.

The six definitions provided for in the code use a combination of at least two and up to all five of the tests listed. However, not all factors within a given test are the same. For example, the age test is applied this way:

- The child and dependent care credits apply only to children under age thirteen;

- There is no age test for dependents or for the education credits;

- The general child tax credit is limited to those under age seventeen; and

- The Earned Income Tax Credit applies for children under nineteen, unless the child is a full-time student, in which case the age limit jumps to twenty-four.

In addition to the above, still another age test applies to the so-called “ ;Kiddie Tax.”50 This is the rule that imposes tax upon a child’s unearned income at the parents’ marginal rate, if the parents’ rate is higher than the rate that would otherwise apply to the child. The “Kiddie Tax” applies to children under the age of fourteen.

This quagmire of definitions ensures that a child living with a given taxpayer is treated one way under one code provision, while that same child may be treated another way—or entirely disregarded—for purposes of other code provisions.

Deduction and exemption phase-outs— The tax code provides deductions for non-business expenses including state and local taxes, mortgage interest, medical expenses, charitable contributions, etc. However, code section 68 phases out those deductions for certain citizens. The phase-out operates to cut the otherwise deductible personal expenses and the phase-out is based solely upon a citizen’s economic standing.

Under current law, when the adjusted gross income of a married couple filing jointly exceeds $100,000 ($50,000 for married filing separately), those citizens lose the benefit of legal deductions under the code that other taxpayers are legally entitled to claim.

Likewise, code section 151(d)(3) phases out personal dependent exemptions in like manner, but based upon other, equally arbitrary adjusted gross income amounts. For example, the dependent exemption phases-out beginning at $150,000 adjusted gross income for married filing jointly ($75,000 for married filing separately). On the other hand, for a single person, the phase out begins at $100,000. Single people lose the full benefit of their dependent exemptions faster than married people, even if the married people have no children. 51

There are examples of phase-outs, exclusions and disparate tax treatments within the code that are too numerous to itemize. They have one thing in common: they are arbitrary in their application as to income thresholds and ceilings. The imposition of these gimmicks ensures that otherwise similarly situated citizens are treated differently under the tax code.

Constitutional Protections Against Arbitrary Taxation

Specific protections against arbitrary and oppressive taxation were built into the Constitution in two specific ways. First, Article I, section 2 provides that “direct taxes shall be apportioned among the several States which may be concluded within this Union.” The second protection is found in Article I, section 8, where Congress is given the power to lay and collect taxes for the purposes prescribed, and further states, “but all duties, imposts and excises shall be uniform throughout the United States.” Following this model, we could never have the kind of tax system that operates in America today.

The requirement that direct taxes be apportioned was to accomplish two purposes. First, it took the federal government out of the business of collecting taxes directly from the people. In this way, the federal government would never have direct contact with the masses of citizens and the latter would never be answerable to a remote federal bureaucracy. To collect a direct tax, the federal government had to present a bill to the respective states equal to each state’s pro rata share of the total, based upon the population of the state. Each state collected the tax through whatever scheme was permitted under its own laws. The state in turn paid it to the federal government.

Secondly, apportioned taxes could never be arbitrary or based upon some other capricious scheme. As Hamilton wrote in Federalist No. 36,

Let it be recollected that the proportion of these taxes is not to be left to the discretion of the national legislature, but is to be determined by the numbers of each State, as described in the second section of the first article. An actual census or enumeration of the people must furnish the rule, a circumstance which effectually shuts the door to partiality or oppression.

On the other hand, indirect taxes, such as excises, etc., must be uniform. 52 In this way, every person pays the same tax, regardless of his social or economic standing. This provision expressly prohibits Congress from using its taxing power as a means to carry out social planning through the vehicle of taxation. That is a key reason Hamilton favored excise taxes over all others as the chief means of raising revenue for the new government. He observed that, “taxes on consumable articles have, upon the whole, better pretensions to equality than any other.”53 Expounding, Hamilton observed that,

The consequence of the principle laid down is that every class of the community bears its share of the duty in proportion to its consumption; which last is regulated by the comparative wealth of the respective classes, in conjunction with their habits of expense or frugality. The rich and luxurious pay in proportion to their riches and luxury; the poor and parsimonious, in proportion to their poverty and parsimony.54

The fundamental protections against tax tyranny as envisioned by the founders were dissolved with the adoption of the Sixteenth Amendment in 1913. This amendment allowed Congress for the first time to lay a tax on income “ without apportionment among the several states, and without regard to any census or enumeration.” Without the Sixteenth Amendment, such a tax was unconstitutional and was so declared by the Supreme Court in the 1895 case of Pollock v. Farmers’ Loan and Trust Co., 55 the case that addressed the first permanent income tax passed by Congress in 1894.

The Sixteenth Amendment opened the door to a condition that was feared by several lawmakers during the debates on the first income tax act in 1913. The fear was that the tax would degenerate into the means whereby it could be used in a “spirit of hatred” simply because certain individuals were more financially successful than others. This concern was best expressed by Massachusetts Senator Henry Cabot Lodge, who said,

It will be an ill day for this country when we raise the cry that success honestly won is to be punished; that money honestly gained is the badge of criminality; and that we are to go to the people of the United States in the search for popularity, and say to them: “Follow us. We will plunder the people who have got the money. You shall spend it, and it will not cost you anything.” That is a dangerous cry to raise in any country, for when you unchain that force you cannot tell where it will stop, and in your eagerness to destroy property and rob men of hope and ambition you may bring your boasted civilization down in ruins about you.56

The Proscription Against Ex Post Facto Laws: “Security from the mischief of the legislature.”

The first object of government is to protect the life, liberty and property of its citizens. The Constitution is a delegation of power to the federal government for the purpose of ensuring the security of the people. Powers not specifically delegated are reserved to the states or the people respectively, or in some cases, denied altogether. The Founders knew that in order to preserve liberty, not only would the broad powers of the legislature have to be restrained, but there would have to be an independent judiciary to ensure that Congress could not overstep its bounds. As Hamilton stated in Federalist No. 78, “Without this, all the reservations of particular rights or privileges would amount to nothing.”

The Founders knew well that the unrestrained power of the legislature was a formula for tyranny. Therefore, in order to preserve the rights of the citizens and insulate them from the mischief of the legislature, several lawmaking powers were outright denied. One such power is the power to pass ex post facto legislation. An ex post facto law is one made to apply retroactively from the date of its enactment. In fact, the Founders were so concerned with ex post facto laws that they precluded both the federal government and the state governments from passing such legislation. These proscriptions are found in Article I, section 9, clause 3 and Article I, section 10, clause 1 of the Constitution.

The language of these provisions is quite plain and simple. In the case of Article I section 9, it states, “No bill of attainder or ex post facto law shall be passed.” There is no proviso or exception expressed in the rule. It was written to apply to all acts of the federal legislature. The Founders understood that all such laws were prohibited, regardless of their subject. In Federalist No. 44, Madison writes,

Bills of attainder, ex post facto laws, and laws impairing the obligation of contracts, are contrary to the first principles of the social compact, and to every principle of sound legislation. The two former are expressly prohibited by the declarations pre-fixed to some State Constitutions, and all of them are prohibited by the spirit and scope of these fundamental charters. Our own experience has taught us nevertheless, that additional fences against these dangers ought not to be omitted. Very properly therefore have the Convention added this constitutional bulkwark in favor of personal security and private rights.

The simple reason for the multiple layers of protection against ex post facto laws was so “the tenure of any property at any time held under the principles of the common law, cannot be altered by any act of the future general legislature.”57

Tax laws are particularly offensive when made to apply retroactively. Under such laws, the citizen is denied the right to plan his personal and business affairs so as to provide for the payment of the tax on time and in the correct amount. Such laws operate to deny the citizen the right to arrange his affairs in such a manner as to legally reduce his tax burden. Moreover, retroactive tax laws unreasonably deny to a person the full use and enjoyment of his property. The power to pass retroactive tax legislation can be particularly oppressive under the current code with its intricate scheme of over 140 civil and criminal penalty provisions.

One example of this is found in the 1993 tax laws promulgated by the Clinton Administration. Section 13208 of the Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act of 1993, 58 was signed into law by President Clinton on August 10, 1993. The law set the maximum federal estate and gift tax rates at 53 percent and 55 percent—effective January 1, 1993.59 This represented an increase of the 50 percent maximum rate that was in effect on January 1, 1993. Thus, under the law, a person dying after January 1, 1993, but prior to August 10, 1993, would have his estate subjected to an increase in tax liability even after death.

Such legislation is expressly forbidden by the plain language of the Constitution. It has been argued that such legislation not only violates the proscription against ex post facto laws, but that retroactive laws actually violate the Fifth Amendment’s due process clause, in that citizens are denied reasonable prior notice of the requirements of the law. Unfortunately, the courts do not see it this way. For years, the Supreme Court and others flaunted the Constitution’s plain language, thereby authorizing retroactive tax laws.

The latest Supreme Court discussion of the issue came in the case of United States v. Carlton.60 In that case, the court visited the question of retroactive estate tax laws designed to correct a flaw in legislation passed by an earlier Congress. The government argued that retroactive legislation was “necessary” to preclude the use by taxpayers of what amounted to an unintended loophole that otherwise existed. Carlton argued that the laws were in violation of the Constitution for a number of reasons.

Writing for the court, Justice Blackmun reiterated prior expressions of the Supreme Court in which retroactive tax and other laws were upheld. The effect of these rules is to wholly gut the protections against legislative intrusion as envisioned by the Founders. For example, the Carlton court said,

Provided that the retroactive application of a statute is supported by a legitimate legislative purpose furthered by rational means, judgments about the wisdom of such legislation remain within the exclusive province of the legislative and executive branches.

The court also stated that ex post facto legislation is permitted when the retroactive period is “modest and not excessive.61 Stated another way, so long as “the retroactive application of the legislation is itself justified by a rational legislative purpose,” Congress has the authority to pass retroactive laws virtually at will, provided the retro active period does not reach back “too far.”

It is interesting to note that the neither the Constitution itself nor the Founders in any of the historical documents authorize the use of ex post facto laws in cases where there is a “rational legislative purpose.” More specifically, the Constitution plainly prohibits the passage of any ex pose facto law—even if such legislation is retroactive by one day.

Throughout the ages, governments have imposed rapacious violations of liberty in the name of “national need” or “compelling governmental purpose.” The clear intention of the Founders, through the plain language of the Constitution, was to eliminate such violations by carefully delimiting legislative power. However, as a result of court decisions such as that discussed above, it seems that citizens are afforded little protection from such legislative intrusions.

Reversing the Foundation of American Jurisprudence: “Innocent until proven guilty.”

The idea of placing the burden of proof upon the accuser derives from English common law. The common law was deeply entrenched in the colonies during the time of the founding and continues as the basis of American law. The common law itself derives from the Great Charter of Liberties, Magna Charta. Magna Charta was the declaration of the liberties of English freemen signed by King John in 1215 AD. It was extracted from the King at the point of a sword as the price for retaining his throne. Magna Charta was reconfirmed numerous times by English monarchs over the ensuing centuries to the point where its principles became engrained in the fabric of English—and by extension, American—jurisprudence.

Chapter 39 of the Great Charter sets forth many of the fundamental rights of citizens in the judicial process. It established the concepts of both due process of law and the burden of proof as we know them today. Chapter 39 (chapter 29 in the 1225 version) reads,

No freeman shall be seized, or imprisoned, or dispossessed, or outlawed, or in any way destroyed; nor will we condemn him, nor will we commit him to prison, excepting by the legal judgment of his peers, or by the laws of the land.

By this declaration, citizens were not to be considered guilty at any level in the judicial process until after a trial. In the Notes on the Great Charters, English jurists declared that the protections afforded by Magna Charta chapter 39/29 are so important that they alone “would alone have procured for it the title of the Great Charter.”62 In practice, this principle created the axiom of law holding that the accuser, whether in the criminal or civil context, was solely responsible to prove the verity of his claims against the accused before any punishment could apply.

Income tax laws and regulations heap upon the shoulders of citizens innumerable requirements to carry out affirmative duties under the pain of imprisonment, civil penalties, additional tax and interest assessments. Moreover, the code allows the IRS to make determinations with respect to a citizen’s filing status, annual income, deductible expenses, dependent exemptions, etc. In all but a few exceptions, the IRS never has to prove that its actions or determinations are correct. The Supreme Court, in the 1933 case of Welch v. Helvering63 declared that the IRS is entitled to the “presumption of correctness” with regard to its determinations. As such, the citizen “has the burden of proving” such actions to be wrong. In a very real way, the consequence of this is that the citizen is essentially guilty until proven innocent, a reversal of the fundamental rule of law regarding the burden of proof. The Supreme Court, in the case of Bull v. United States, used this explanation to describe how the litigation process is fundamentally altered in tax cases:

Thus, the usual procedure for the recovery of debts is reversed in the field of taxation. Payment precedes defense, and the burden of proof, normally on the claimant, is shifted to the taxpayer. The [tax] assessment supersedes the pleading, proof, and judgment necessary in an action at law, and has the force of such a judgment. The ordinary defendant stands in judgment only after a hearing. The taxpayer often is afforded his hearing after judgment and after payment, and his only redress for unjust administrative action is the right to claim restitution.64

The shift in the burden of proof does not apply to the various criminal provisions of the tax code. To place the burden of proof on the accused in a criminal matter is a clear deprivation of due process and flatly unconstitutional. However, the vast majority of the penalty provisions of the tax code are civil in nature and it naturally follows that the overwhelming number of penalty assessments are likewise civil in nature. As a result, the courts seem content to dissolve the historic protection in most civil cases.

But despite the fact that the imposition of civil penalties does not carry the risk of loss of liberty, such imposition, as well as civil collection in general, most certainly does imply the loss of property, a condition Magna Charta referred to as being “dispossessed.” As the evidence presented above clearly shows, the Founders put the importance of property and the protection thereof on par with that of personal liberty. The due process clauses of both the Fifth and Fourteenth Amendments speak clearly to the protection of life, liberty and property.

What could justify a departure from the settled principles of due process such that the burden of proof is shifted from the government to the citizen? The answer is found in a statement by the Bull court that has become a common thread woven into the fabric of tax litigation for more than six decades. That statement is, “But taxes are the lifeblood of government, and their prompt and certain availability an imperious need.”65 Thus, in the mind of the Supreme Court, the government’s “imperious need” for money justifies the abandonment of one of the most important elements of American liberty.

The concept of “need” was reiterated in the case of Carson v. United States, where the Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals more pointedly declared that such departure is justified based upon “the government’s strong need to accomplish swift collection of revenues and in the need to encourage taxpayer recordkeeping.”66

This reasoning presents a recurring theme: government’s need for money is, by itself, sufficient to override settled constitutional protections. This notion is antithetical to liberty and to the notion of a government with limited, narrowly prescribed powers. If the courts are able to set aside specific constitutional protections on the mere assertion by the government of a “compelling need,” all the rights declared sacrosanct in the Constitution are but empty vessels.

This shift in the burden of proof is responsible for innumerable abuses by the IRS. Many of these were brought to light during the 1997 Senate Finance Committee hearings into IRS abuse. Specifically, the practice of placing the burden on taxpayers has the effect of allowing the IRS to issue penalty assessments at will, without regard to the specific facts of a case and in violation of its own stated policy on penalty assessments. A good share of the more than thirty million penalties issued every year are issued through automatic computer assessments. In this way, the IRS does not even make an effort to determine whether the facts of a case justify imposition of the penalty. The taxpayer is left to assert defenses if he is able to navigate the procedural quagmire.

This is equally true of the millions of computer notices issued by the IRS annually. Many such notices claim to correct errors allegedly made by citizens in their tax returns. And while the law provides a means for a citizen to challenge these notices,67 the burden is on the citizen to correctly respond to the notice in a timely fashion, craft a response sufficient to apprise the IRS of the objection and prosecute the objection through the system while carrying the burden of proving not only that the IRS’ determination is incorrect, but what the correct determination should be.

The unfortunate reality is that the vast majority of citizens embrangled with the IRS do not understand their rights or legal remedies under the code. As such, people fail to realize that they are in fact “prosecutors” when it comes to correcting errant IRS action. That is to say, the citizen must instigate appeal actions, both administrative and judicial, in order to challenge a tax audit determination. The citizen must instigate proper challenges to collection actions in order to prevent the loss of property in the collection process. The citizen must instigate administrative or judicial challenges to the IRS’ investigative powers in the hope of maintaining any right of privacy. In the context of all such challenges (with rare and narrow exceptions), the citizen must carry the burden of proving IRS error, with respect to both the law and facts of the case.

The extensive focus on the burden of proof issue led Congress to enact code section 7491 as part of the Internal Revenue Restructuring and Reform Act of 1998. This provision received much attention because it purports to shift the burden of proof to the IRS, thereby curing the problems set forth above. On careful inspection, however, it can be said that that law cannot possibly attain that goal.

Section 7491(a)(1) states as follows,