Introduction

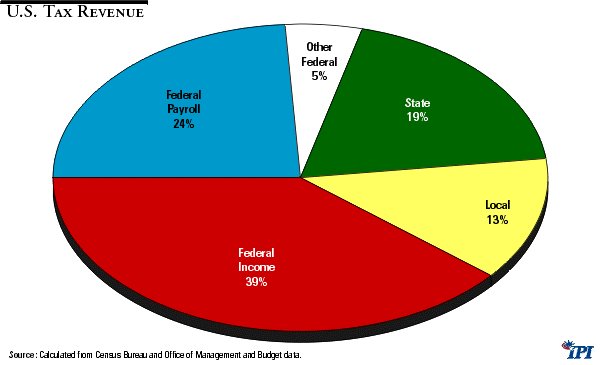

When politicians debate tax rates they usually focus on federal income taxes. But despite all the attention given to income taxes, they are just a fraction of the total taxes Americans bear. In fact, total personal income taxes represent much less than half (42 percent) of Americans’ tax burden. 1

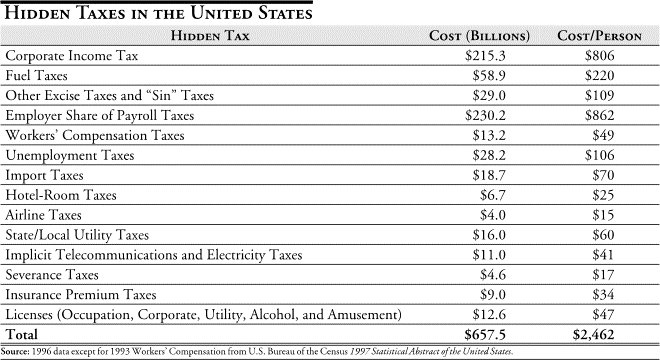

This paper identifies $657.5 billion in additional “hidden” taxes, or $2,462 in hidden taxes per person.2 These hidden taxes violate a basic principle of taxation — that taxes should be visible to the people who pay them. If people don’t accurately perceive how much government policies cost them, then how can they make informed decisions in our democratic process?

As Steve Entin, President of the Institute for Research on the Economics of Taxation points out, “Visibility requires that the tax system reveal clearly to the citizen/taxpayer what he or she must pay for government goods, services, and activities. Taxes are the ‘price’ we pay for government ; taxes ‘cost out’ government for the taxpayer.”3

While many Americans associate a lack of visibility in the tax code with excise and value added taxes, the visibility of some taxes is impaired by the fundamental public misunderstanding of who actually pays taxes. Many believe corporations pay taxes when economic reality demonstrates they do not; the tax burden is displaced to individuals. Yet very few taxpayers are cognizant of this fact. Income tax withholdings and the employer’s share of payroll taxes are further examples of taxes whose clouded visibility continues to mislead the average taxpayer with respect to how much he or she really pays in taxes.

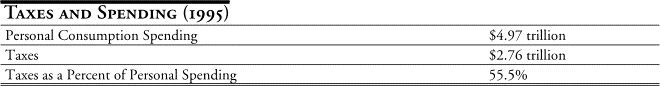

Some taxes are inadvertently hidden, but others are consciously designed that way to disguise the cost of government. It’s easy to see why: the total U.S. tax burden is equal to 56 percent of annual personal consumption spending. 4 If Americans recognized this high level of taxation, there might well be a second American Revolution.

Americans are subject to numerous different taxes. The many types and levels of taxation help explain why taxes are so steep: giving governments more ways to tax usually encourages higher tax burdens.5 Figure 1 shows the relative magnitude of different U.S. taxes.

Figure 1

Table 1

How Many Taxes are Hidden?

For the purposes of this paper, a hidden tax is one that is not explicitly clear to the taxpayer. For example, sales taxes generally are not considered to be hidden taxes, because the costs are clearly indicated on cash register receipts. Many regulations, mandates, and other government policies have been described as hidden taxes because of the costs they impose on Americans. However, this paper focuses primarily on tax policy, not a broader definition of hidden taxes.6 Table 2 graphically demonstrates the impact of several hidden taxes.

Table 2

Corporate Income Taxes

In 1997, federal, state, and local governments collected over $215 billion in corporate income taxes, or the equivalent of $806 a person. 7 Many individuals believe that figure represents $215 billion that the rest of us don’t have to pay. Some critics claim that corporations should pay even more in taxes.

On the surface, taxing corporations instead of people may sound appealing. However, it’s not that simple, since corporations are people working as a legal entity. In addition, when the government imposes corporate income taxes, the potential responses include:

- Raising prices

- Lowering payments to stockholders

- Reducing employee compensation and capital investment

Under any of the three options, Americans end up paying the tax either through lower wages if they work for a corporation, poorer performance if they own a mutual fund, or higher prices when they buy a product.8 But this tax burden doesn’t show up on any pay slip or price tag.

Hidden corporate taxes impose an even greater burden because they represent double-taxation. When a company earns a profit, it pays taxes on that money. When it pays its stockholders a dividend, that same money is taxed again. This double-taxation discourages much-needed investment. Harvard economist Dale Jorgensen calculates that double-taxation reduces our national wealth by about a trillion dollars.9

Everyone who owns a mutual fund or IRA, or who participates in a 401(k) or typical pension plan, is penalized by this double-taxation. Even relatively low-income Americans increasingly rely on stocks for a portion of their savings. According to the Federal Reserve Bank, from 1989 to 1995 the share of stocks as a percent of total assets doubled for families with incomes under $25,000.10

Gas and Other Transportation Taxes

How much does a gallon of gasoline cost? Many Americans might be surprised by the answer, because the price to actually produce and deliver the product is much lower than the amount posted at the pump.

According to the American Petroleum Institute, the average price for a gallon of gasoline as of August of 2000 was $1.48 per gallon. However, this statistic is highly misleading: 43 cents of the price consisted of gasoline taxes. 11 In other words, gas taxes inflated the price of gasoline by 37 percent.

Unlike sales taxes, gas taxes don’t appear anywhere on the receipt after you fill up. Lucky motorists may find the state and federal tax rate in small print somewhere on the gasoline pump. But since the total amount they pay is hidden, most Americans don’t recognize the tax burden when they buy their gas, and they certainly have no idea of the annual cost of gas taxes.

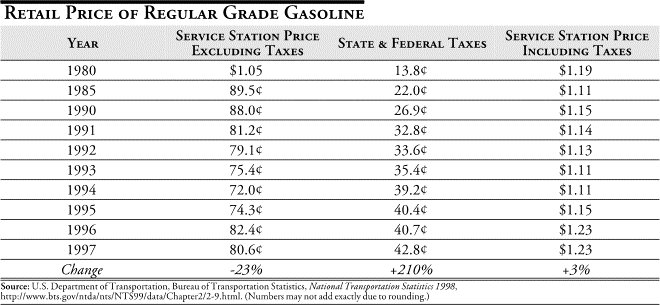

As Table 3 shows, gas taxes haven’t always been so high. While the pre-tax price of gas fell sharply between 1980 and 1996, this decline coincided with an increase in gas taxes that resulted in the final retail price of gas remaining virtually unchanged.

Table 3

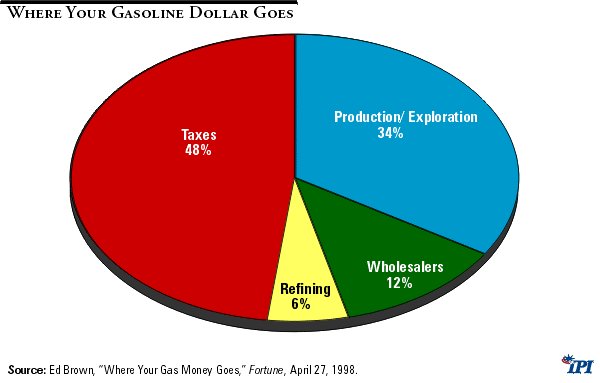

When you buy a gallon of gasoline, the government receives the largest chunk of your money. According to one report, for a dollar’s worth of gasoline, 34 cents are accounted for by exploration and production, refining takes up 6 cents, wholesalers get a nickel, and the service station owner gets 12 cents. As Figure 2 shows, taxes take up the rest.

Figure 2

Stephen Moore of the Cato Institute concludes that in recent years gas taxes have been the fastest-growing federal tax imposed on middle-income Americans. 12 In 1999, the federal government discarded the scheduled reduction in taxes of 4.4 cents per gallon.13 Fuel taxes cost Americans $58.9 billion, or $220 per person.

“ Sin” Taxes

The gas tax is just one example of an excise tax. Unlike retail sales taxes, which are clear to consumers, excise taxes are imposed on producers. As a result, the final cost of excise taxes is often hidden from consumers. These taxes lower consumption of the taxed product and increase consumption of other products. Because they distort people’s spending decisions, excise taxes can be a particularly costly way for governments to raise money.

In general, most experts believe that tax policy should be neutral — it should neither favor nor discriminate against specific goods or services. While policymakers often follow this advice, a notable exception to this rule is provided by taxes on items that the government decides are unhealthy, like products containing alcohol and tobacco. These “sin” taxes provide a major source of excise tax revenue. Since consumers of these products often lack the political clout to counter the attractive revenue stream available to taxing authorities, sin taxes have been an especially attractive tool to finance government spending. Some examples of sin taxes follow.

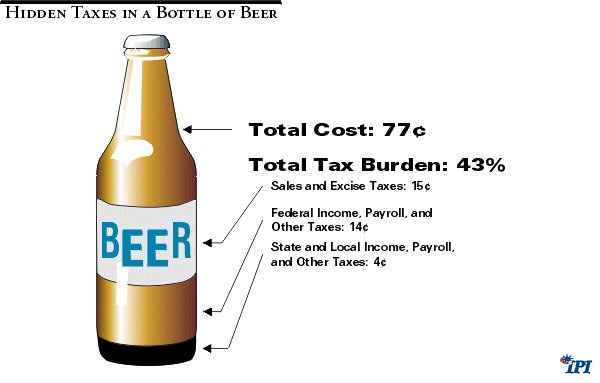

Beer Taxes: Many taxes are raised during wartime but never returned to their original level. For example, the federal government hiked beer taxes to help pay for the Korean War. The taxes were maintained after the war, and then doubled in 1991. According to the consulting firm of DRI/McGraw Hill, 43 percent of the cost of each six-pack comes from taxes, versus a 30 percent tax component for most other consumer goods. Therefore, if not for taxes, a $5.00 six-pack would cost just $2.85. Adam Thierer of the Heritage Foundation observes that beer taxes tend to be regressive, with about two-thirds of the beer sold in America bought by households earning less than $45,000.14

Figure 3

Liquor Taxes: Not surprisingly, taxes on so-called “hard” liquor tend to be even more punitive. Combined local, state, and federal taxes account for close to half (45 percent) of the cost of distilled spirits. Tax revenues from liquor are many times higher than the total profits of distillers. As with beer taxes and other sin taxes, distilled spirits taxes are regressive. According to one study, these taxes are five times greater as a percent of income for lower-income families as for their higher-income counterparts.15

Tobacco Taxes: Tobacco products are portrayed even more negatively than alcoholic beverages, so taxing users of these products is correspondingly popular with government officials. However, like other sin taxes, tobacco taxes are also very regressive. The Joint Economic Committee concludes that at the federal level, two-thirds of cigarette taxes come from smokers who earn less than $40,000 per year. According to the Tax Foundation, the recent 15 cents per-pack tax hike left smokers earning less than $15,000 a year with 34 percent of the tax burden.16

The federal tax on a pack of cigarettes is scheduled to increase to 34 cents per pack in the year 2000 and 39 cents per pack in 2002, with much higher taxes currently under consideration. State taxes vary from 2.5 cents to a dollar per pack. Cigars are subject to a federal tax of up to 12.75 percent, chewing tobacco is taxed at 12 cents per pound, and pipe tobacco is taxed at 67.5 cents per pound. The Clinton Administration’s FY2001 budget projects $45 billion in tobacco tax revenue from FY 2000 to FY 2005.17

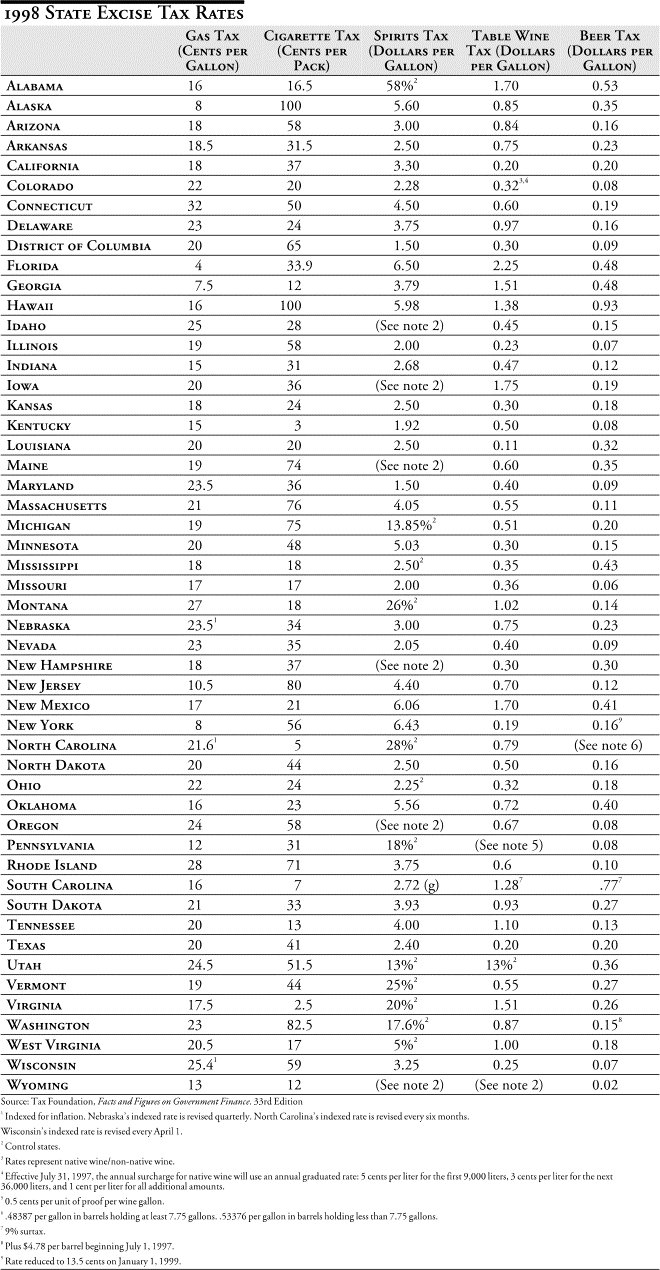

Appendix Table A1 shows each state’s excise tax rate for gasoline, cigarettes, distilled spirits, wine, and beer.

Other Excise Taxes

The federal government levies several other excise taxes, including:

Vaccination Taxes: The government imposes a 75-cent per dose excise tax on vaccines for DPT (diphtheria, pertussis, tetanus), DT (diphtheria, tetanus), MMR (measles, mumps, or rubella), polio, HIB (haemophilus influenza type B), Hepatitis B, varicella (chickenpox) and rotavirus gastroenteritis.18

Firearms Taxes: The government imposes a 10 percent excise tax on pistols and revolvers, an 11 percent tax on other firearms, and an 11 percent tax on shells and cartridges. 19

Phone Taxes: A federal excise tax on telephone services, first imposed to fund the Spanish-American War, will cost taxpayers $5.5 billion in 2000.20 On top of this amount, governments historically have subsidized universal service through regulations that boost phone bills for some users in order to subsidize others. One study put the cost of this hidden tax at $5 billion. 21

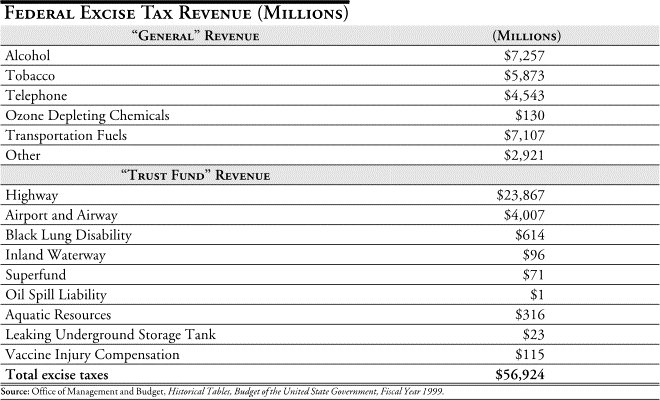

On the positive side, deregulation is leading toward replacement of “ implicit” hidden telecommunications regulatory subsidies with “ explicit” tax-financed subsidies. Making the subsidy explicit to taxpayers will increase pressure to control taxes. As Table 4 indicates, combined federal excise tax revenue alone comes to $57 billion.

Table 4

Examples of How Taxes are Hidden in the Price of Goods

Americans for Tax Reform (ATR) has calculated several examples of how taxes affect the purchase price of several goods and services. The ATR figures include the impact of all taxes — not just certain hidden taxes — on prices. According to ATR:

• Taxes account for 35 cents of the cost of a $1.14 loaf of bread.

• 18 cents of a 50-cent can of soda go toward taxes.

• 72 percent of the cost of a 750-ml bottle of liquor goes toward taxes.

• Taxes for an $80 hotel room average 43 percent.

• Taxes account for $63.60 of a $159 airline ticket.

• A $153.09 monthly utility bill consists of $39.35 in taxes.

• Over half the cost of a $1.33 gallon of gasoline is due to taxes.22

A 1992 Cato Institute study looked at taxes somewhat differently, calculating how much someone needed to earn to have enough after-tax dollars to purchase several products. The study concluded that a typical worker needed to earn $17,038 to buy a $10,000 car, and $2,556 to purchase a $1,500 computer.23

Telecommunications Taxes

State and federal governments have indirectly taxed some telecommunications users and subsidized others for years. The government first imposed telecommunications taxes to help finance the Spanish-American War. Today, the impact of these taxes can be significant: according to the cellular industry, a combination of fees and mandates force consumers to pay 20 to 30 percent more than the actual cost of providing cellular service.24

For many years, the cost of telecommunications subsidies was hidden in Americans’ phone bills. As part of the move to deregulate the industry, the 1996 Telecommunications Act was supposed to make these costs explicit. However, it also opened the door to a big increase in telecommunications taxes. The Act stated:

Consumers in all regions of the Nation, including low-income consumers and those in rural, insular, and high cost areas, should have access to telecommunications and information services…that are reasonably comparable to those services provided in urban areas and that are available at rates that are reasonably comparable to rates charged for similar services in urban areas.…Elementary and secondary schools and classrooms, health care providers, and libraries should have access to advanced telecommunications services.25

In other words, the Act suggested that residents in low-cost areas should continue to pay more to subsidize service for Americans who choose to live in high-cost areas, and it authorized additional support for schools, libraries, and rural health care providers. As a result, universal service subsidies (sometimes referred to as the GoreTax due to the Vice President’s active and vocal support of the program) were established to provide subsidized access to the Internet to all public schools and libraries in the nation. It raised approximately $2.25 billion last year.26

Subsidizing rural customers is not necessarily good policy. Kent Lassman of Citizens for a Sound Economy explains:

Ted Turner owns a 160,000-acre ranch in Montana. For $8.45 million, Turner recently purchased 44,000 acres in Nebraska to bring his holdings in the Cornhusker State to more than 96,500 acres. With more than 15,000 bison grazing on his land in Montana, Nebraska and New Mexico, Turner-the-Rancher can afford a few of life’s luxuries — yet he does not pay the full cost of telephone service.27

Even if it makes sense to subsidize high-cost users, financing those subsidies by taxing telecommunications services does not. As Stephen Entin pointed out, “[T]he government provides universal access to food by giving needy people food stamps and welfare checks. This assistance is funded out of general federal revenues, not by an excise tax on groceries or a mandated ‘ contribution’ by food stores to a ‘Food Fund.’”28

FCC Commissioner Harold Furchgott-Roth estimated that the total cost of federal universal access policies could require a 10 percent tax on interstate services on top of the preexisting 3 percent tax.29 Many rural states want an even bigger subsidy.

As National Taxpayers Union President John Berthoud observed: “[B]efore one dime is taken, at a minimum, taxpayers should have the ability to address elected officials on the topic, and then later hold them accountable. It violates any and all basic tenets of democratic representation to allow unelected officials to levy taxes on the American public.” 30

“Explicit” Costs?

While the 1996 Act was supposed to make taxes and subsidies more explicit, from the government’s perspective, providing such clear information also would increase opposition to government subsidies. Therefore it was not particularly surprising when several companies complained that although the FCC wanted them to fund new universal service programs, they were not supposed to inform their customers of the cost. Randall Coleman of the Cellular Telecommunications Industry Association argued, “They don’t want us to call it a tax. But that’s exactly what it is.”31

Sprint Corporation commented: “[A] lthough the Commission did not prohibit carriers from passing through their USF (Universal Service Fund) costs to end users, the Commission did bar carriers from labeling any USF cost recovery charge on their bills a ‘USF surcharge’ (emphasis added).”32

Many Americans might prefer to see the reduced cost of service reflected on their phone bills instead of used to offset new government spending. Former FCC Chairman Reed Hundt admitted that higher subsidies translates to higher prices: “It’s a very small additional subsidy.…It will be contributed by communications companies. Will they pass it onto somebody? Yes, they’ll pass it on to everyone in America in insignificant ways down to…pennies a day. It will be a collective action by all of America.” 33

Payroll Taxes

Income Tax Withholding

When tax day comes around each year, many Americans are happy to get a check from the federal government, even though they’re just getting back their own money — without interest. This is a case where visibility concerns may not be immediately recognized — a warped case of the exception proving the rule. Most American’s wouldn’t associate income tax withholdings as a “hidden tax,” and yet — for that very reason — they are one of the most insidious of the hidden taxes. Clearly, one will be more conscious of what one pays in income taxes if one is required to write a check out to the United States Government once a year. Instead Washington has cleverly designed a system that takes small amounts of our income every pay period so the loss is not as apparent. This hidden tax is hidden right under our noses.

Since income tax payments are withheld from their paychecks, the true burden of paying taxes is much less visible to them. This principle of tax collection is similar to the advice offered by many financial planners to have money automatically deducted from your paycheck for investments, since you don’t miss the money as much that way. As David Brinkley commented:

Congress and the president learned, to their pleasure, what automobile salesmen had learned long before: that installment buyers could be induced to pay more because they looked not at the total debt but only at the monthly payments. And in this case there was, for government, the added psychological advantage that people were paying their taxes with not much resistance because they were paying with money they had never even seen.34

Withholding increased the burden on taxpayers in two ways. First, money that previously could have been gaining interest in the bank or invested in the economy now was preemptively taken by the government. Second, making income tax costs less visible in turn made tax increases much more feasible.

Today, withholding is widely accepted. House Majority Leader Dick Armey (R-TX) initially proposed elimination of withholding in his flat tax plan, describing withholding as a “crucial, deceptive device” that permits the government to “raise taxes to their current level without igniting a rebellion.”35 Rep. Armey later removed this feature from his plan.

Employer Share of Payroll Taxes

Another classic example of a hidden tax of which the majority of Americans are completely unaware is the share of payroll taxes supposedly paid for by the employer. Again, to have visibility the taxpayer must be aware of how much he or she is paying in taxes. If the average taxpayer assumes the employer’s share of payroll taxes is actually paid by the employer and the opposite is true, visibility is hardly achieved.

According to the government, payroll taxes for Social Security and Medicare are “paid equally by both employees and employers,” with each paying 7.65 percent.36 While that may be true for accounting purposes, economist Walter Williams explains how it really works:

[Y]ou probably already believe…that your employer pays half your Social Security. This lie may be demonstrated by pretending that you’re my boss. We agree to a wage of $7.00 an hour. You deduct 50 cents an hour as my Social Security contribution and add 50 cents as the “employer contribution,” ; making your cost to hire me $7.50 an hour. My question is: If it costs you $7.50 to hire me, what is my minimum hourly output for you to keep me on the job and stay in business? If you said $7.50 an hour, go to the head of the class, because you also know who pays all of the Social Security tax. The worker does.37

Williams observes that the government maintains the myth that employers pay half of Social Security and Medicare taxes because Americans would “go ape” if they knew the true tax burden these programs impose.

The government uses payroll taxes to help finance Social Security and Medicare spending, including Old Age and Survivors Insurance (OASI), Disability Insurance (DI), and Hospital Insurance (HI, or Medicare Part A). When the government first imposed these taxes during the 1930s, the rate was a combined 2 percent for earnings up to $3,000 per year. The 1998 combined rate was 15.3 percent: 12.4 percent for OASDI for the first $68,400 of wage income, and 2.9 percent for HI for all labor income.38

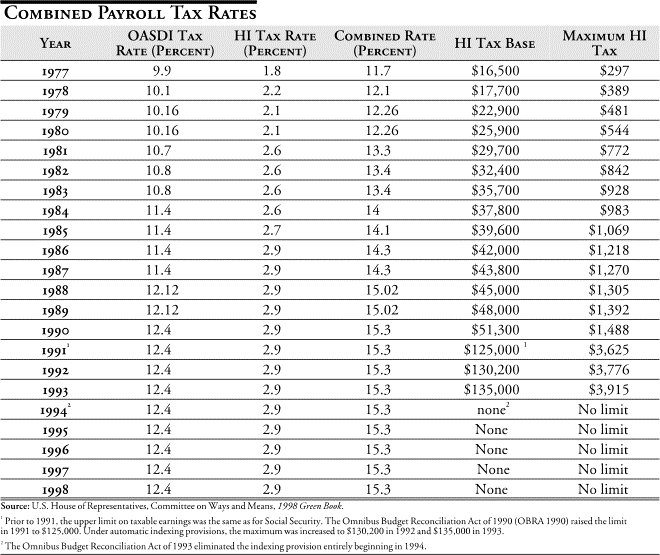

Payroll taxes have increased dramatically since 1937. According to the Institute for Policy Innovation, over 90 percent of American workers pay more in payroll taxes (including the “employer’s share”) than they do in income taxes.39 Table 5 illustrates the rise in payroll tax rates in recent years. Since 1977, the payroll tax rate has grown by nearly one-third, from 11.7 percent to 15.3 percent — and that doesn’t include the big increase in the wage base subject to payroll taxes.

Table 5

The government collected $502.7 billion in Social Security and Medicare payroll taxes in 1997. Deducting the amount paid by self-employed workers, which is not hidden, leaves a rough estimate of $460.5 billion in combined employer and employee taxes. The hidden portion of this comes to $230.2 billion, or $862 per person.40

Unemployment and Workers’ Compensation Taxes

Around the same time the government instituted Social Security, it mandated that states set up unemployment insurance programs. Unemployment insurance, along with mandatory workers’ compensation insurance for on-the-job injuries, is a hidden tax that lowers employees’ wages.

Since unemployment insurance is mandatory, workers who stay employed help finance payments to frequent job-changers. As George Leef observed, “ [T]hose workers who seek and hold steady jobs are being compelled to subsidize the unemployment of workers who choose employment which is apt to be sporadic.”41

Unemployment insurance can also extend the amount of time people stay out of work. According to Harvard University’s Martin Feldstein, “For those who are already unemployed, it (unemployment insurance) greatly reduces and often almost eliminates the cost of increasing the period of unemployment.” ;42

The Impact of Hidden Labor Taxes:

A recent Cato Institute study documented the impact that hidden labor taxes have on America’s workforce. The report found that while an average full-time manufacturing worker earns about $27,200, it costs employers $31,000 to hire the worker due to workers’ compensation, unemployment insurance, and the employer’s share of Social Security and Medicare taxes.43 As the study points out, this money otherwise would have gone to the employee.

After deducting income and payroll taxes from his paycheck, the worker keeps just $22,400. The total “tax wedge” from labor taxes is $8,600, or 28 percent of the amount the employer pays. The amount rises to 36 percent for employees earning $60,000, nearly half of which does not appear on the pay stub.44

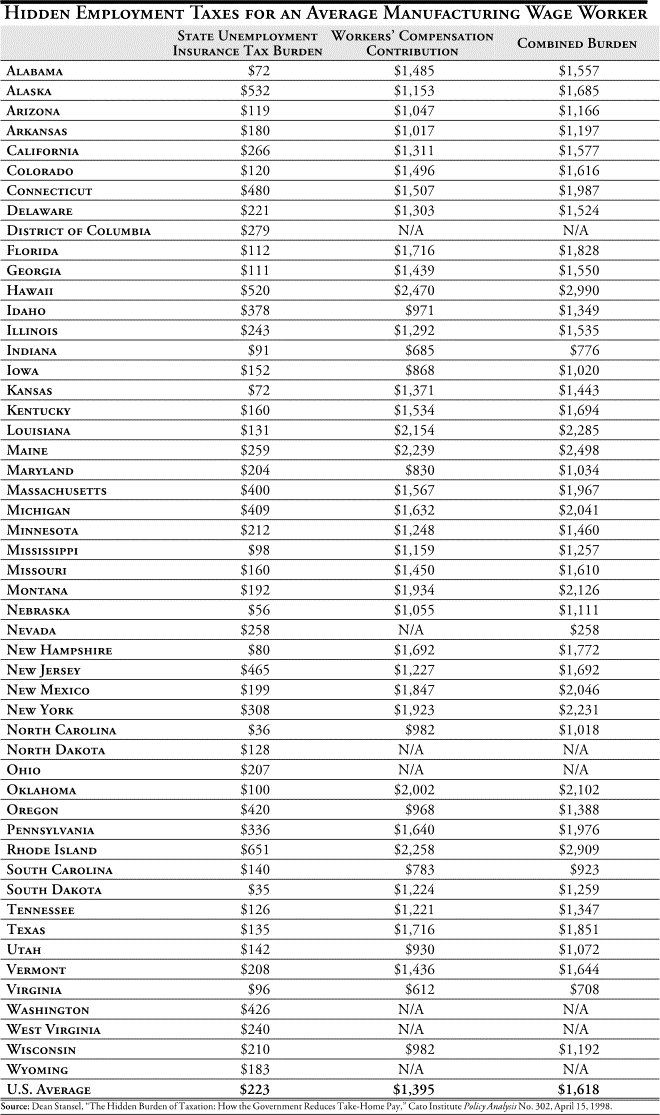

The average burden imposed by unemployment insurance and workers’ compensation taxes is $1,618 per employee.45 Appendix Table A2 shows the burden for each state. Table 6 gives a breakdown of employee compensation costs.

Table 6

Since mandated benefits raise the cost of hiring workers, they destroy jobs and lower wages. An analysis of federal labor laws, Social Security, and unemployment compensation laws from 1934 to 1940 found that these policies boosted the median unemployment rate to 17.2 percent from 6.7 percent.46

Import Taxes

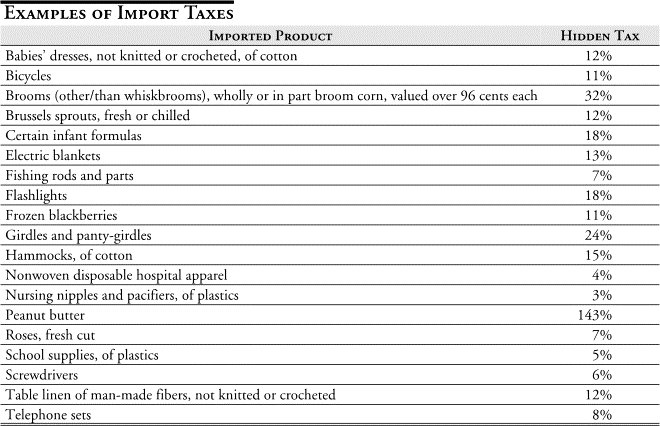

Americans pay $18.7 billion in taxes on imported products, or $70 per person. As Table 7 shows, these taxes hit a broad range of products.

Table 7

Import taxes also boost the price of U.S.-made products. When interest groups persuade Congress to protect their industry from competition at the expense of the rest of the country, they can charge higher prices than they would be able to maintain in a competitive marketplace.

Travel Taxes

Hotel and Car Rental Taxes

While the phrase “no taxation without representation” strikes a chord with many Americans, it’s often politically attractive to impose a tax on those who are unable to vote. This process, called “exporting” taxes, helps explain the popularity of hotel and car-rental taxes in many communities. Politicians can tax out-of-town voters to finance local projects, often at a stiff price. The specter of room taxes ranging up to 17 percent and additional car rental taxes can be an unwelcome surprise for American travelers.

One bed-and-breakfast owner described the problem: “Here in Massachusetts we have a 5.7% room occupancy tax. In addition, towns are permitted to add their own local tax, so in the same area, the tax may be different depending on the specific town. Many people don’t know this and are perturbed to find out how much more they are paying for a $125 room.”47 Another owner observed: “Lodging establishments tend to despise the room tax, the main reason being that the local governments spend the funds on things other than promoting tourism and lodging.”48

Nationwide, bed taxes average 11.7 percent, or $9.19 per night. Tax rates are as high as 17 percent in Houston, and average more than $24 per night in New York City. As of 1997, bed taxes cost $6.7 billion, or $25 per person. 49 Car rental taxes average 8.24 percent.50

Hotel and car rental taxes are becoming an especially popular tool to finance new sports stadiums. According to one report, at least 18 cities already have used these taxes to fund stadiums, with as many as 20 more close behind. 51 One analyst called travel taxes the “hottest trend” in stadium financing, adding that “…these types of financing are sailing through local city councils and municipalities.”52

Most travelers who rent a car or stay at a hotel don’t benefit from the stadiums their taxes help finance. According to the Travel Industry Association, only about 5 percent of travelers include attendance at a sporting event in their activities.53

Airline Ticket Taxes

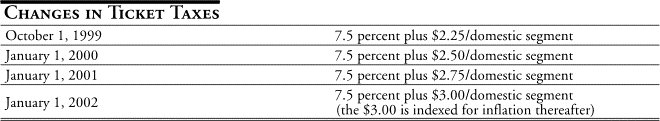

Airline ticket taxes are currently 7.5% percent of the fare plus $2.75 per domestic flight segment. The tax rate is scheduled to change as shown in Table 8.

Tables 8

In addition, the tax for international departures recently was doubled to $12 per passenger and extended to apply to return flights.54 The government imposes many other hidden costs on air transportation, including a $4.50 per person passenger facility charge levied by local governments but approved by the federal government.55

The burden that ticket taxes impose on travelers was highlighted when they temporarily expired during budget fights between President Clinton and Congress. When the tax was reinstated in 1996, airlines passed the cost along to consumers. As one story reported at the time, “Major U.S. airlines have raised domestic fares 10 percent, anticipating a 10 percent excise tax that President Clinton is expected to sign into law today.”56

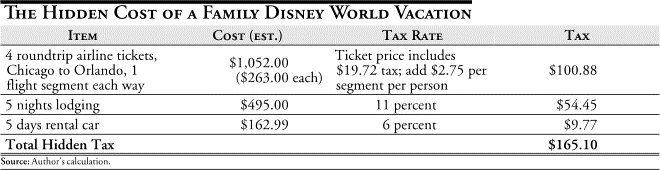

Table 9 shows the impact of hidden vacation taxes for a family headed from Chicago to Orlando.

Table 9

Southwest Airlines Chairman Herbert D. Kelleher recently summed up the effects of hidden taxes on his industry when he wrote: “The Customer is only truly aware of the total fare. If that is perceived as being too high, the airline receives the blame and suffers the economic consequences if the Customer chooses not to travel or to travel by other means [emphasis in original].”57

Other Hidden Taxes

Bracket Creep

Perhaps the hidden tax that most fundamentally violates the principle of visibility is bracket creep. One side effect of inflation is that in a progressive tax system, taxpayers will be bumped into higher tax brackets even if their real income is unchanged. In the late 1970s, high inflation rates caused middle-class taxpayers to face marginal tax rates far higher than Congress initially intended. To prevent further bracket creep, in 1981 Congress voted to index federal tax rates and exemptions for inflation.58

Unfortunately for most taxpayers, few states have taken similar precautions to protect taxpayers from bracket creep. Only eight of the states that impose income taxes automatically adjust their brackets, exemptions, and deductions for inflation.59 This hidden “inflation tax” falls hardest on lower-income taxpayers, since inflation sends them into higher tax brackets. Those already paying the maximum rates are unaffected by bracket creep. While the impact of bracket creep is different for each state, Ohio provides an example of how this hidden tax works. According to a Buckeye Institute study, the tax rate for a married couple each earning $6 an hour was ten times higher in 1997 than it would have been if Ohio’s tax code had made allowances for inflation when it was adopted in 1972.60

Severance Taxes

Most states impose a variety of severance taxes on natural resources when producers “sever” them from the Earth. These taxes apply to a wide array of products, ranging from oil and gas to turpentine and timber. While the taxes are visible to the initial producers, they are hidden from consumers who buy the finished goods that are made from natural resources. State severance taxes cost Americans $4.6 billion in 1997, or $17 a person.

Utility Taxes

Public utilities provided state and local governments with $16 billion in tax revenue in 1997, or $60 per person. These taxes often are hidden from consumers. According to the Edison Electric Institute (EEI), one state imposes taxes that add 25 percent to electricity bills, but then prohibits a separate line-item on bills that would inform customers of their tax burden.61 EEI also calculates that utilities pay a total of $25.8 billion in taxes of all kinds.

Utility regulations also force some electricity users to pay higher prices to subsidize other users. The U.S. Department of Energy estimates that these subsidies cost about $6 billion.62 As with telecommunications deregulation, energy deregulation should provide the opportunity to make these taxes more explicit and therefore possibly lower.

Insurance Premium Taxes

State taxes on insurance premiums cost Americans $9.0 billion in 1997. These taxes average $34 per person, a cost that often is hidden in the price of insurance.

Licensing

Most states impose a broad range of licensing requirements on different segments of the economy. One of the more prevalent examples is the use of occupational licensing. The rationale for these licenses is usually to protect consumers’ health and safety, but in reality they are often just hidden taxes that restrict competition for the regulated profession.

As Nobel prize-winning economist Milton Friedman and his wife Rose commented: “The justification [for licensure] is always the same: to protect the consumer. However, the [real] reason is demonstrated by observing who lobbies at the state legislatures for imposition or strengthening of licensure. The lobbyists are invariably representatives of the occupation in question rather than its customers.”63

An example of licensing in practice is provided by the case of Monique Landers, a high school student who opened a hair-braiding business and won an award from the National Foundation for Teaching Entrepreneurship. But since she didn’t have a cosmetology license, the state shut her down. According to Landers, “The (state Cosmetology) Board won’t let me earn my own money, and won’t let kids like me learn how to take care of ourselves. I think owning your own business is a way of being free. If more kids knew they could grow up to be their own boss they would be more responsible and cause less trouble.”64

In some states, Mary Kay representatives and their counterparts from other companies can’t even help their customers apply makeup unless they first get a cosmetology license.

These hidden taxes drive up taxes for consumers, but they also limit opportunities to enter many professions. Several studies have concluded that licensing is especially detrimental to individuals from minority groups. According to Dan Hogan, “The reliance of licensing laws on academic credentials — which are less frequently possessed by the poor, minorities, women, and the elderly — has a deeply pernicious and discriminating effect, especially when evidence does not exist that these credentials are positively correlated with competence.”65

Total state licensing, including occupational and corporate licensing, cost $12.6 billion in 1997, the equivalent of $47 per person.

Electronic Commerce

Use of the Internet is booming, and along with it online sales of goods and services. According to the U.S. Commerce Department:

• Internet access grew from 171 million people worldwide in 1999 to 304 million in 2000.

• U.S. employment in “Internet Technology” (IT) positions has risen from 4.3 million jobs in 1994 to 5.3 million Americans employed in the IT business in 1998.

• Between March of 1999 and March of 2000 Internet access in the United States grew by more than 40 percent.66

This development has not escaped the eye of state taxing authorities. As the Chairman of California’s Tax Board noted:

Instead of applying traditional legal concepts to the taxation of electronic commerce, state tax bureaucrats are becoming legal contortionists in an attempt to tax Internet sales. The resulting confusion among prospective Internet merchants and service providers could substantially impede the development of electronic commerce.67

Some states tax access to Internet service providers like America Online, an especially questionable practice since the providers may be located in another state.

A recent Commerce Department report gave several principles for Internet taxation: “The application of existing taxation on commerce conducted over the Internet should be consistent with the established principles of international taxation, should be neutral with respect to other forms of commerce, should avoid inconsistent national tax jurisdictions and double taxation, and should be simple to administer and easy to understand.” 68

In 1998, Congress approved the Internet Tax Freedom Act. This law restricts multiple taxation of Internet commerce by state and local governments and imposes a three-year moratorium on new state or local taxation of Internet access.69 Sen. Bob Smith (R-NH) has introduced legislation to extend these moratoriums indefinitely.

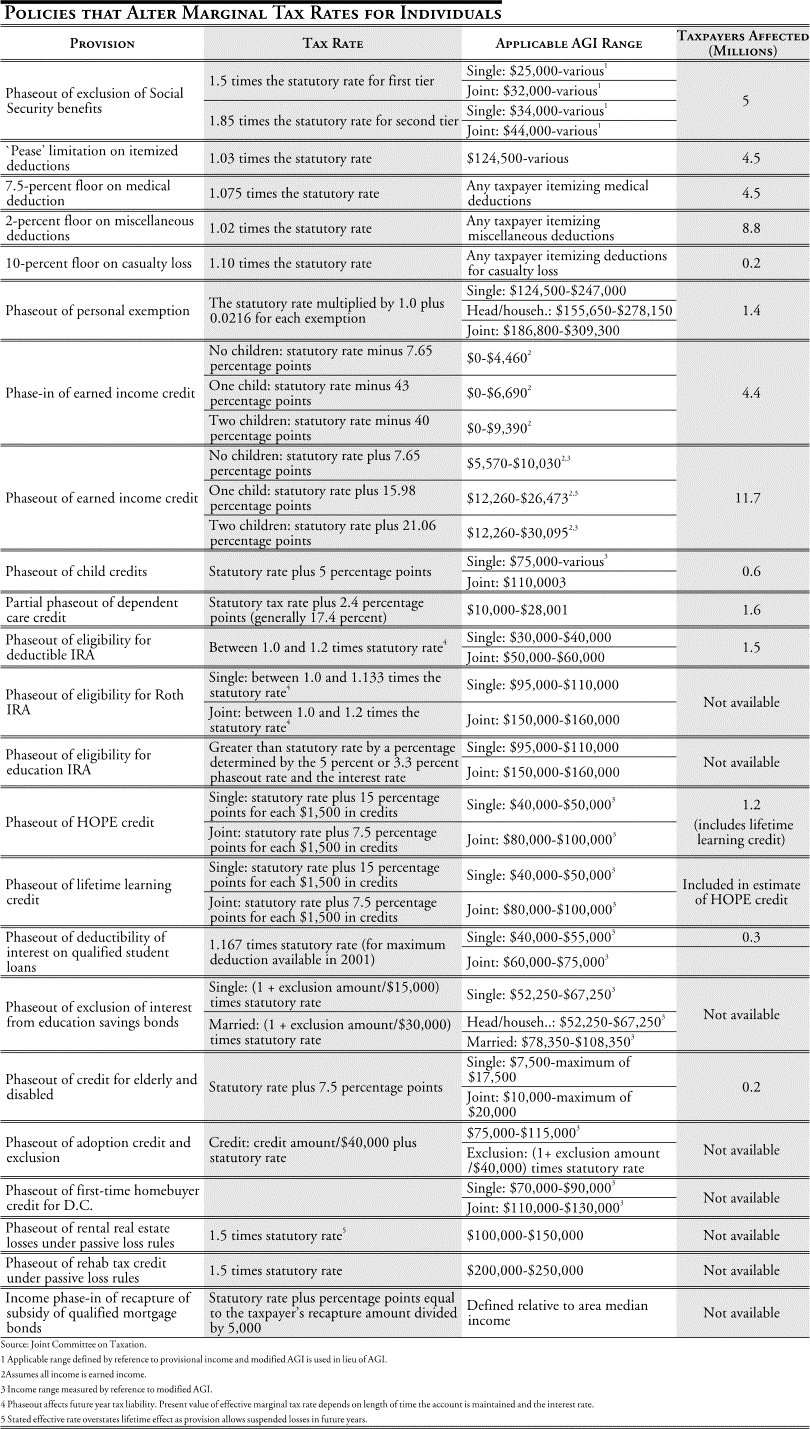

Phase-Outs of Deductions

Similar to bracket creep, deduction phase-outs have a visibility of nearly zero. While other hidden taxes have been described in dollar terms, there are many policies buried in the federal tax code that serve as hidden taxes by forcing people to pay higher-than-normal marginal tax rates — the rate paid on an additional dollar of income. The U.S. Joint Committee on Taxation (JCT) recently reported on 22 provisions that can make a taxpayer’s marginal tax rate differ from the statutory rates of 15, 28, 31, 36, and 39.6 percent.

The JCT concluded that two taxpayers with similar incomes may face very different marginal tax rates. For example, older Americans can face marginal tax rates of greater than 90 percent. All told, the JCT found that 33.2 million taxpayers face effective marginal tax rates that differ from the statutory rate.70

The Social Security benefits tax provides an example of how effective marginal tax rates can differ from statutory marginal tax rates. Up to half of Social Security retirement benefits are taxable for taxpayers with modified adjusted gross income thresholds between $25,000 and $34,000 ($32,000–44,000 if married filing jointly). In other words, once reaching $25,000, an additional dollar of income adds 50 cents of Social Security benefits to taxable income. This provision makes the effective tax rate 50 percent higher than the statutory rate. Appendix Table A3 gives a complete list of the measures identified by the JCT that alter marginal tax rates.

William Gale of the Brookings Institution concluded that some of these provisions should be repealed:

The personal income tax contains several “take-back” provisions. These taxes are imposed even when a taxpayer is complying perfectly with the law but ends up with what the law has deemed “too many” deductions or “too little” taxable income. These items represent hidden taxes, they distort incentives, they raise little revenue, and, most crucially, they create unnecessary complexity. They should simply be repealed.71

Gale identified four features in particular for possible repeal: phaseouts of personal exemptions, limitations on itemized deductions, taxes on excess pension accumulations and payouts, and the individual alternative minimum tax (AMT).

To simplify these numerous and complex phaseouts, the American Institute of Certified Public Accountants (AICPA) has proposed combining many of them into just three schedules.72

Empowering Voters with Information

Hidden taxes cost the average American at least $657.5 billion — much more if the cost of income-tax withholding is included. When taxes are not visible, Americans are unable to evaluate whether they’re getting their money’ ;s worth from the government. As a result, hidden taxes help to boost the size of government.

Commenting on hidden telecommunications taxes, American Enterprise Institute Fellow James Glassman put his finger on the problem: “The idea here is an old one: People can’t rebel if they’re kept in the dark.” 73

In addition to increasing the size of government, hidden taxes are an especially harmful way to raise money. Hidden taxes distort the prices that Americans face, causing them to over-consume some products and under-consume others. As a result, hidden taxes inflict more economic damage than broad-based, visible taxes.

And even though governments have an incentive to hide the cost of taxes, there are opportunities to make taxes more visible even without government action. Many utility companies now include the cost of taxes as a line item on their monthly billing statements. More companies could take similar steps to itemize the cost of taxes — gas stations, for example, could more prominently display the cost of taxes or even tell consumers their tax bill every time they fill up.74

According to a survey by the Fund for Stockowners Rights, only 154 major companies — 15 percent of all corporations — disclosed the total direct and hidden taxes they paid in their annual reports.75 This can prevent taxpayers from understanding that the overall burden of taxation on the economy matters as much, if not more than, who pays the taxes. And in an age when millions of Americans are joining the ranks of individual investors, such information is critical to understanding the bottom line. Perhaps more companies will provide facts to shareholders on the taxes that they pay in the near future.

On the payroll side, the Mackinac Center for Public Policy has developed a “Right to Know Payroll Form” that employers can distribute with their paychecks. The form shows the hidden cost of policies including the “ employer’s share” of payroll taxes and the cost of mandated workers’ compensation and unemployment insurance.76 As Joe Lehman from the Mackinac Center commented, “The Right to Know Payroll Form isn’t anti-government or pro-government. It’s just giving people information. Still, it’s perfectly possible that a worker can look at these numbers, see what government costs him, and conclude that he’s getting a good deal. This is all just information. It doesn’t tell you what conclusions to draw.”77

While these examples of increased visibility are encouraging, much more must be accomplished. As many different factions continue to debate which type of tax reform is best for America, all sides would do well to remember that one of the fundamental tenets of tax reform must be visibility. Without it, tax reform cannot be truly successful.

In 1999, the Minnesota Department of Revenue sponsored a “Citizens Jury® on Minnesota Property Tax Reform” in conjunction with the Jefferson Center to debate and discuss reform of Minnesota’s property tax. Their criteria for a visible tax could provide tax reform advocates in Washington with the basic guidelines necessary to ensure visibility in the tax code. Reiterating a theme from the beginning of this paper, they determined that “[f]or the link between taxing and spending to have any meaning, people must be aware of the taxes they pay.” They identified three factors that help define visibility:

• Form : Is it part of or separate from an economic transaction. (sic) If it is part of an economic transaction, it is less visible. Sales taxes and income taxes (i.e. withholding) are part of an economic transaction.

• Size : If the tax payment is relatively small it is less visible.

• Frequency : If the tax is paid often, then it tends to be less visible.78

While the numerous hidden taxes discussed above are not responsible for every inequity contained within our current tax code, they do contribute significantly to the most complex and inherently unfair system of taxation ever placed upon the American public. Its overhaul is imperative. The fundamental focus of any and all reform must be on visibility. For a hidden tax is an unknown tax, and an unknown tax is one that cannot be evaluated and judged by those who pay it.

In his work The Republic, Plato suggests that what people believe to be truth is comparable to image. He demonstrates this principle in his allegory of the cave in which he describes a man imprisoned from birth in a cave. He is chained down and able only to look forward. Behind him is light. It projects shadows of everything that passes between him and the light on the wall in front of him. To him, the shadows are reality. They are his only source of information and sensory stimulus and therefore his only basis for reality. To be able to discover true reality, however, he must free himself and venture out of the cave. Only then will he experience the reality of our world.

Congress has imprisoned American taxpayers in a cave where the tax code they see is merely a distorted image of what they truly pay in taxes. Only through reform and total visibility will taxpayers clearly realize the current level of taxation imposed upon them. Until then, the tax code will continue to be what it is today: a grossly distorted shadow that cannot, and should not, pass for the truth.

Endnotes

- Author’s calculations from FY 2002 Federal Budget Historical Tables, and U.S. Census Bureau’s Federal, State, and Local Governments Finances.

- Not including withholding of income and payroll taxes from paychecks.

- Steve Entin, “The Inflow Outflow Tax — A Savings-Deferred Neutral Tax System,” Institute for Research on the Economics of Taxation.

- Personal consumption spending from Bureau of Economic Analysis National Income and Product Accounts, http://www.bea.doc.gov/bea/newsrel/pi0600.htm; total tax burden from U.S. Census Bureau, Statistical Abstract of the United States: 1999 (119th Edition) Washington, DC, 1999.

- For example, states without an income tax tend to have a lower tax burden than states that maintain an income tax on top of other taxes, and countries that impose value-added taxes in addition to income taxes tend to have a higher tax burden than those that don’t. See Richard Vedder, “State and Local Taxation and Economic Growth,” http://www.senate.gov/~jec/sta&loc.html.

- According to Americans for Tax Reform, Americans must work more than half the year on average to finance the total cost of government, including regulatory, paperwork, and other costs. See http://www.atr.org/.

- Author’s calculation from Office of Management and Budget, Historical Tables, Budget of the United State Government, Fiscal Year 1999 , and population data from the U.S. Bureau of the Census.

- For a more detailed exploration of this issue, see “The Incidence of the Corporate Income Tax,” Congressional Budget Office, March 1996.

- In Daniel Mitchell, The Flat Tax: Freedom, Fairness, Jobs, and Growth , The Heritage Foundation, 1996, p. 13.

- Arthur B. McKinnickell, Martha Starr-McCluer, and Annika E. Sunden, “ Family Finances in the U.S.: Recent Evidence from the Survey of Consumer Finances,” Federal Reserve Bulletin, January 1997, p. 11.

- American Petroleum Institute, http// www.api.org.

- Stephen Moore, “Give Motorists a Tax Break,” Cato Institute Commentary, December 2, 1997.

- Office of Management and Budget, Analytical Perspectives, Budget of the United States Government, Fiscal Year 2000, p. 48.

- Adam Thierer, “Heady With the Power to Tax Beer,” Washington Times, September 15, 1996.

- “No More Increases in the Federal Excise Tax on Distilled Spirits,” Distilled Spirits Council of the United States Fact Sheet, http://www.discus.health.org/nomorfet.htm.

- “Soak the Poor?” Investor’s Business Daily, April 15, 1998.

- Office of Management and Budget, Analytical Perspectives, Budget of the United States Government, Fiscal Year 2001, p. 91.

- Office of Management and Budget, Analytical Perspectives, Budget of the United States Government, Fiscal Year 2001, p. 50.

- Commerce Clearing House, U.S. Master Tax Guide (Chicago, IL: CCH Incorporated, 2000) para.54, “Excise Taxes.”

- Office of Management and Budget , Analytical Perspectives, Budget of the United States Government, Fiscal Year 2001, p. 91.

- “What is the Price of Universal Service?: Impact of Deaveraging Nationwide Urban/Rural Rates,” Telecommunications Industries Analysis Project, Cambridge, Mass., 1993, cited in Wayne Leighton, “What to Do About Universal Service Subsidies: Support for High-Cost Areas,” Citizens for a Sound Economy Issue Analysis Number 39, September 30, 1996.

- “Taxes, Taxes, and More Taxes,” Washington Times editorial, August 25, 1996; see also www.atr.org.

- George Nastas and Stephen Moore, “A Consumer’s Guide to Taxes: How Much Do You Really Pay in Taxes?,” Cato Institute Briefing Paper No. 18, April 15, 1992.

- News release, “Cellular Telecommunications Industry Association (CTIA) Hails Introduction [of] House & Senate Legislation to Repeal the 3% Federal Excise ‘Tax on Talking,’” April 1, 1998.

- Telecommunications Act of 1996, section 254.

- “Tauzin, Bliley Move to List ‘Gore Tax’ on Phone Bills,” Brody Mullin, National Journal’s Congress Daily, October 5, 1999.

- Kent Lassman, “Somebody is on the Take: Universal Service at Home on the Range,” Washington Times, February 16, 1998.

- Stephen J. Entin, Institute for Research on the Economics of Taxation, “ Hidden Phone Tax a Bad Way to Pay for Internet Access,” IRET Congressional Advisory, December 30, 1997, p. 2.

- The Honorable Harold Furchgott-Roth, “FCC Report to Congress on Universal Service,” FCC 98-67, April 10, 1998, p. 138.

- Statements of The Honorable James C. Miller III, Counselor, Citizens for a Sound Economy, and John E. Berthoud, Ph.D., President of the National Taxpayers Union, before the U.S. House of Representatives Committee on the Judiciary, Subcommittee on Commercial and Administrative Law, February 26, 1998.

- In James K. Glassman, “A New Tax for the New Year,” Washington Post, December 2, 1997.

- “Comments of Sprint Corporation before the FCC,” CC Docket 96-45, January 28, 1998, p. 2.

- FCC Chairman Reed Hundt, “Notable and Quotable,” Wall St. Journal , June 23, 1997, p. 18.

- In Charlotte Twight, “Evolution of Federal Income Tax Withholding: The Machinery of Institutional Change,” Cato Journal, Vol. 14 No. 3.

- Cited in Charlotte Twight.

- U.S. House of Representatives, Committee on Ways and Means, 1996 Green Book , November 4, 1996.

- Walter Williams, “Medical Benefit Fact and Fiction,” Washington Times, Nov. 27, 1989, p. F3.

- U.S. House of Representatives, Committee on Ways and Means, 1998 Green Book .

- Gary and Aldona Robbins, “Tax Deduction for Payroll Taxes: An Analysis of the Ashcroft Proposal,” IPI Quick Study, 1997, p. 1.

- Estimate based on payroll tax revenue from Budget of the United States and employment data from the U.S. Small Business Administration.

- George C. Leef, “Time to Rethink Unemployment Insurance,” Mackinac Center for Public Policy Research Viewpoint on Public Issues , December 7, 1992.

- Martin Feldstein, “Unemployment Compensation: Adverse Incentives and Distributional Anomalies,” National Tax Journal , June 1974, p. 231, cited in George Leef.

- Dean Stansel, “The Hidden Burden of Taxation: How the Government Reduces Take-Home Pay,” Cato Institute Policy Analysis No. 302, April 15, 1998.

- Source: Dean Stansel (Cato Institute), “Concealed Pay Bites,” Washington Times, April 14, 1998.

- Dean Stansel, “The Hidden Burden of Taxation: How the Government Reduces Take-Home Pay,” Cato Institute Policy Analysis No. 302, April 15, 1998.

- Richard Vedder and Lowell Gallaway, Out of Work: Unemployment and Government in 20th Century America (Oakland, CA: Independent Institute, 1992).

- Erni Johnson, December 16, 1997, http://www.innsite.com/innkeeping/archives/9712/0035.html.

- Bob Weinman, December 15, 1997, http://www.innsite.com/innkeeping/archives/9712/0019.html.

- American Hotel Foundation, Impact of Tax Increases in the Lodging Industry, 1998, p. 3.

- Travel Industry Association of America News Release, “17 Cities Sock it to Travelers to Pay for Stadiums,” December 4, 1996.

- Susanna P. Barton and Sougata Mukherjee, “Tourism Taxes for Stadiums Draw Fire,” Jacksonville Business Journal, April 7, 1997.

- Marty Greenberg, director of the National Sports Law Institute at Marquette University, quoted in Barton and Mukherjee.

- In Barton and Mukherjee.

- Office of Management and Budget, Analytical Perspectives, Budget of the United States Government, Fiscal Year 1999.

- P.L. 106-181

- Greg Groeller and Susan Miller, New York Times News Service, “Airlines Beat Clinton to Increasing Fares: President Will Reinstate Today the 10 Percent Excise Tax on Tickets,” August 20, 1996.

- Herbert D. Kelleher, letter to House Committee on Transportation and Infrastructure Chairman Bud Shuster, June 15, 1998.

- Michael R. Baye and Dan A. Black, “Indexation and the Inflation Tax,” Cato Institute Policy Analysis No. 39, July 12, 1984.

- Federation of Tax Administrators, “State Individual Income Tax Rates,” ; http://www.taxadmin.org/fta/rate/ind_inc.html.

- Samuel Staley and Robert Lawson, “Ohio Keeps Poor Down with Unfair Taxes,” Buckeye Institute Perspective, April 1997, p. 1.

- Edison Electric Institute, “Why Doesn’t Electricity Cost the Same Everywhere?,” Electric Utility/Restructuring Issues, http://www.eei.org/Industry/structure/power3.htm.

- U.S. Department of Energy news release, “Administration’s Plan Will Bring Competition to Electricity, Savings to Consumers,” March 25, 1998.

- Milton Friedman and Rose Friedman, Free to Choose (New York: Harcourt, Brace, Jovanovich, 1979), p. 240.

- Monique Landers, cited in Cascade Update , Cascade Policy Institute, Spring/Summer 1994, p. 2.

- Dan B. Hogan , The Regulation of Psychotherapists, Vol. I: A Study in the Philosophy and Practice of Professional Regulation (Cambridge, Mass.: Ballinger Publishing, 1979) p. 282, and in Stanley J. Gross, “Professional Licensure and Quality: The Evidence,” Cato Institute Policy Analysis No. 79, December 9, 1986, p. 27.

- U.S. Department of Commerce, Digital Economy 2000, June, 2000.

- Dean F. Andal, California Tax Board Chairman, letter to Rep. Chris Cox (R-CA) and Sen. Ron Wyden (D-OR), March 12, 1997.

- U.S. Department of Commerce, The Emerging Digital Economy , Chapter 3, “Electronic Commerce Between Businesses”, April 15, 1998.

- Public Law 105-277, October 21, 1998. See http://www.house.gov/cox/nettax/ for details.

- Joint Committee on Taxation, “Present Law and Analysis Relating to Individual Effective Marginal Tax Rates,” February 3, 1998.

- William G. Gale, “Tax Reform is Dead, Long Live Tax Reform,” Brookings Institution Policy Brief No. 12.

- “AICPA Legislative Simplification Proposal on Phase-Outs Based on Income Level,” January 1998, http://www.aicpa.org/.

- James K. Glassman, “A New Tax for the New Year,” Washington Post , December 2, 1997.

- On the other side of the coin, some companies may prefer to keep the cost of taxes hidden. For example, retailers trying to sell a $300 suit might not want their customers to know that the suit is actually worth much less after taxes are taken into account.

- Fund for Stockowners Rights News Release, “1997 Company Annual Reports Highlight Heavy Tax Impacts,” January 20, 1999.

- See www.macjinac.org for more information.

- “Showing Government’s Burden,” Investor’s Business Daily Perspective, April 1, 1997, p. B1, http://www.mackinac.org/topics/special/special.htm.

- “Citizens Jury® on Minnesota Property Tax Reform,” Jefferson Center, August 2-6, 1999, Appendix A.

Appendix

Table A1

Table A2

Table A3