The U.S. is once again embarking on a national debate over health care reform, and many Americans want to embrace a system similar to those of Europe or Canada. This study includes nine papers from a number of economists and health policy experts from those countries. These experts reveal how their governments are micromanaging their health care systems by imposing price controls, limiting access to prescription drugs, hindering research and innovation, and exerting political control over health spending decisions. As a result, patients face long waiting lines, often go untreated, or are treated with old and outdated technologies.

The Central Dilemma of Health Care Reform

Do centralized, government-controlled systems deliver better outcomes than the private sector? Helen Disney of the Stockholm Network compares elements of European and the U.S. health care. She concludes that Europeans are living on borrowed time, and unless their health care systems are reformed rapidly and decisively, the consequences for patients will be dire.

Germany: How Not to Organize a Health Care System

Is Germany a model for reform? Wilfried Prewo of the Centre for the New Europe says that the quality of care in the German system is good and that patients are free to choose their doctors; as a result, waiting lists for surgeries are short. However, the main reason why the standard of care in Germany is considered satisfactory is not because of the intrinsic quality of the public system, with its 90 percent market share. Rather, the driver for high quality is competition with 10% of the health sector run through private insurance.

Britain: Determined to Depend Solely on Tax Funding

Stephen Pollard of the Centre for the New Europe analyzes Britian’s National Health Service and the Labour Party’s efforts to reform it. In effect, he says the story of Labour’s health policy has been a giant step backwards, followed by years spent returning to the status quo ante of 1997. Ultimately, Labour has no choice but to rely on ever-greater contracting out of services to the private sector.

Swiss Health Care: A Clockwork Model that Fails to Keep Promises

Switzerland employs a different health care model than other European countries. Alphonse Crespo, M.D., of the Institut Constant de Rebecque in Lausanne, Switzerland, argues that limited government intrusion, strong and innovative health industries, reputable medical schools and a market economy have provided quality care to all levels of Swiss society for many decades. But growing government involvement is changing that and threatening the country with the most market-oriented health system in Europe.

Sweden: Losing Faith in Top-Down Regulation

Fredrik Erixon of the European Centre for International Political Economy says that as in every other country in the developed world, health care expenditures in Sweden have increased rapidly in recent years. The country is also expanding parallel trade for prescription drugs. But government management is faltering as the system still faces cost pressures. Under the newly-elected government, Sweden is beginning to take steps toward expanding private sector options in health care delivery.

Why Canadians Pay Less for Drugs than Americans

Brian Lee Crowley of the Atlantic Institute for Market Studies in Canada argues that to lower U.S. drug prices to Canadian levels, the U.S. would have to cut its standard of living by 20 to 30 percent and reform its ludicrous product liability laws. And pharmaceutical industry profits would have to be squeezed through price controls and dominant-purchaser policies, thus causing lower levels of pharmaceutical investment and innovation and thereby reducing the likelihood of treatments for diseases we cannot yet cure or control.

The Dangers of Limiting Drug Choice: Lessons from Germany

Valentin Petkantchin with the Institut Economique Molinari looks at the growing problems with reference based pricing of prescription drugs. In the end, U.S. government officials should think twice before deciding to implement extensive European-style mandatory public drug coverage and its cost containment counterparts. Instead, U.S. policymakers should rely more on patient choice with market-based health insurance and individual responsibility to cover its costs.

The Effect of Price Controls on Drug Innovation in Italy

Alberto Mingardi of the Instituto Bruno Leoni in Rome says the Italian government is walking a fine line, limiting the availability of new drugs and leading more than 50 percent of patients to say they feel there is a need for more precise and frequent information on newer treatments and drugs.

What Can U.S. Health Care Reformers Learn from Europe?

Johan Hjertqvist of the Health Consumer Powerhouse presents the findings of the Euro Health Consumer Index, which is the only benchmark tool that compares European health care systems from the consumer’s point of view. The most important lessons from Europe are that monopolies serve consumers badly and that top-down reform is inefficient and difficult. Consumers’ desire for choice and empowerment is far stronger than many governments realize.

Introduction

The U.S. is once again embarking on a national debate over health care reform, one that will engage both the states and Congress and will likely influence the outcome of the 2008 presidential campaign.

The debate will include both facts and faith—especially faith on the part of some people that somewhere, somehow, someone has figured out how to create a government-run health care system that actually works. It is an act of faith because a well-functioning government-run health care system has never actually existed. Regardless of the country—Great Britain, France, Italy, Sweden or Canada—they all face limited funding, rationed care, and restricted choices. All of them.

But that fact has done little to diminish the hope that it can be done successfully, if only the U.S. will try.

Given the prevalence of the faith in government-run health care, the Institute for Policy Innovation, the Galen Institute, and the International Policy Network asked a number of economists and health policy experts from Europe and Canada to write brief chapters on issues facing their countries’ health systems. The papers are offered in this publication and also were presented during briefings in Washington, D.C., in the fall of 2006.

What these experts expose are governments often obsessed with micromanaging the health care system: imposing price controls, limiting access to prescription drugs, hindering research and innovation, and cutting government health care budgets. And the result is millions of patients facing long waiting lines, going untreated, or treated with old and outdated technologies—all because of the heavy hand of government in micromanaging health care.

Not everything about these countries’ health care systems is bad, of course. Some elements work well. They do try to achieve universal coverage, and, of course, they spend less money than we do in the U.S. But they also get less. Access to the newest technologies and latest therapies, especially drug therapies, is limited. Doctors may be very well trained, but health facilities can look like those of a less-developed country. And express government approval is often required if a patient needs therapy that is outside the norm.

Moreover, fiscal pressures are building. Shifting from a market-based health care system to a government-run system may seem harmless for a while because the new system lives off the old capital infusions. But as government constrains spending, capital infusions decline and the infrastructure begins to deteriorate. And what should be a private investment decision based on the likely needs of patients—Does a hospital need a new CT scanner or PT scanner?—becomes a political decision because someone has to allocate limited government funds, which means someone wins and someone loses.

As these authors demonstrate, health care in Europe is in transition. Governments are struggling to find ways to meet the growing demands of an aging population. Consumerism is building as patients want more say over their health care choices. And public systems are under serious financial strain, resulting in alternative private systems emerging in many countries. And while these changes are proving a challenge to the Europeans, they can provide some valuable lessons for the U.S.

That’s because the U.S. health care system is also in transition, from a doctor-directed system to a patient-directed system. Insurers, employers and providers are all looking for ways to engage the patient as a consumer and provide incentives for them to be value-conscious shoppers in the health care marketplace. Some of the European models are moving, ever so slowly, in that direction as well.

Are there lessons we in the U.S. can learn from the health care systems of Europe and Canada? You can be the judge. These essays can help shed light on whether these countries should be a model for U.S. reform.

Merrill Matthews

Institute for Policy Innovation

Grace-Marie Turner

Galen Institute

Julian Morris

International Policy Network

____________________________________________

The Central Dilemma of Health Care Reform

By Helen Disney

Delivering health care services in the modern world is becoming increasingly difficult, even as high-quality health care becomes ever more desired.

Governments all over the world—regardless of the type of system they preside over—are having to find new ways of delivering cheaper, faster, more sophisticated treatments and services to a wider range of patients and consumers.

At the core of the politics is a key dilemma—do centralized, government-controlled systems deliver better outcomes than the private sector?

Europe vs. the U.S. In Europe, this dilemma is often (wrongly) posed as follows: a private system means an American system. The American system is viewed by Europeans as being immoral and neglectful because millions of poor people don’t have health insurance. Thus, Europe does not want an “American” (i.e., free market) system, and any effort to decentralize a European system stalls due to the negative political implications of being seen to be like the United States.

In America, on the contrary, certain critics of the U.S. system—which indeed has its faults, as do all health care systems—tend to go misty-eyed when thinking about the merits of European health care systems. Despite the previous failure of Democratic attempts to create a “universal health care system” (sometimes dubbed “Hillarycare,” after President Bill Clinton’s concerted effort to pass sweeping health care reform legislation) in 1993, they argue that government-funded and/or government-managed systems are fairer, cheaper, and more efficient than the U.S. system. Look at what these systems achieve, they say, they spend less of their of GDP on health care and avoid all the hassle of insurance policies, HMOs, employer-based coverage, the uninsured, and so on.

Is the European health care system vision superior to the U.S.? Or is the U.S. model better? And what lessons can the U.S. learn from centralized systems?

The European Trend. On the whole, the broad growing trend across Europe is a move away from centralized, government-controlled health care. Examples abound of countries trying to decentralize, outsource or de-politicize health care. Sweden, Slovakia and the UK in particular have been working hard to reform their systems, introducing more competition and choice and moving away from the model of the state doing everything.

Most recently in the UK, the Conservative opposition has even proposed a National Health Service (NHS) Independence Bill to take the day-to-day running of the NHS out of the hands of politicians, just as the Labour government of 1997 gave independence to the Bank of England.

The policy reveals a stark truth about centralized health systems: They suffer from a state of permanent revolution as reforms are introduced and then repealed according to the direction of the political wind. In the case of the current Labour government in the UK, they “re-centralized” the NHS and overturned many of the Conservatives’ internal market reforms on principle, only to reintroduce them under a different name a few years later, when Labour realized how useful they actually were.

Variations in the Systems. First, a few definitions, since it is impossible to speak of Europe en masse when it comes to health care. European systems differ widely but can be broadly categorized as follows:

Tax-funded government monopolies (“Beveridgean” systems): Most health care is publicly funded and often publicly provided by government agencies or publicly funded employees, although in recent years most Beveridgean systems have begun a partial privatization of the supply of health care.

The Beveridgean systems subdivide roughly between Northern European countries such as the UK and the Scandinavian countries, where systems are mainly centralized, and the Southern European countries such as Spain and Italy, where there is a greater regional focus and more devolved decision-making.

Social insurance (“Bismarckian”) systems: A mixture of public and private funding and “mixed provision” operates in countries such as Germany and the Netherlands. 1 A compulsory level of basic insurance is topped up with a range of other insurance products. Employers and employees pay income-related premiums. The unemployed are covered by the state.

So, Europe is not a uniform system, just as the U.S. is not really a “free market” in health care, given the large degree of government provision through Medicare and Medicaid.

Evaluating a Health Care System. Let us also say at the outset that there is no perfect model of a perfect health care system. And let us also say that being scientific about health care outcomes is not simple either. How are we to measure what constitutes a successful health system? Should we use life expectancy or access to new treatments as a measure? Or should we be more subjective and ask consumers what they think? Are waiting times a good measure, or should we look at how efficiently the health system spends its budget?

If we take each of these measures in turn, we should at least be able to get a picture of how systems measure up in comparative analysis.

According to the Central Intelligence Agency’s World Factbook, life expectancy at birth in the U.S. is 77.85, a little lower than the European Union (EU) average of 78.3. Perhaps not a huge difference but, taken individually, some EU countries such as Sweden perform much better, with a life expectancy at birth of 80.51, the seventh highest in the world. In the U.S., some states such a Minnesota also perform better than the national average.

Of course, life expectancy is affected by many other factors such as genetics, diet and levels of exercise, and so may not be an ideal indicator of health system performance.

So, what about other indicators? In Europe, the Health Consumer Powerhouse (HCP) now ranks health systems according to a series of indicators of their consumer-friendliness. 2 In the most recent analysis, the countries in the EU that come out best are those like France, Germany and Sweden which have a higher degree of competition and choice and a more mixed economy of provision.

Countries such as the UK, which ranked 15th, or the former communist states such as Czech Republic (22nd) and Latvia (24th), which come close to the bottom of the rankings, are those which remain highly centralized both in terms of organization and financing, with a largely taxpayer-funded system still in place.

Such centralized systems tend to have certain features in common, which mainly reflect the lack of consumer power to effect change. In other words, patients become resigned to poor care provided by the central system because they cannot do much to change it—unless they are wealthy enough to opt-out and pay out of their own pockets for better or faster treatment.

Broadly speaking, the HCP analysis shows that waiting times are longer under centralized systems, access to new medicines is rationed more strictly, usually due to the lower levels of funding, and patients tend to be more frustrated with the service they are offered.

Public Satisfaction. Looking at public attitudes to health care systems across Europe, as the Stockholm Network has done in two consecutive studies, “Impatient for Change” and “Poles Apart?”, this frustration emerges in a variety of ways, with users questioning their lack of access, choice, and quality at the national level. 3

Waiting for treatment is now a key political concern in Europe, with 83 percent of Europeans regarding waiting times as important to good quality health care, but only 26 percent rating their respective health services as good in this regard.

In all of the countries polled, with the exception of Spain at 46 percent, well over half of the respondents identified reform as an urgent priority.

The New Competition. Significantly, the debate is now going beyond the context of the nation-state. The gradual opening up of borders within the European Union is promising to turn what were once stand-alone country systems into an integrated health service market. This trend is still at an early stage, and the numbers of people travelling abroad for treatment are hard to pin down. But they appear to be growing from the hundreds to the thousands. Such a development will gradually reveal weaknesses among the national systems, as health consumers begin travelling abroad to get the treatment their home country denies them or can only offer them to an inferior standard.

The Stockholm Network’s two studies bear this out, with younger generations displaying a markedly higher willingness to travel abroad for treatment, as long as treatment is paid for by their health system. Some 64 percent of all those polled would travel to another country for treatment if their own health system paid, rising to as many as three quarters among young people.

We also asked respondents to rank their system with a simple mark out of ten. As in the HCP analysis, France (at 6.9) emerged as the most popular of all the European systems measured. But even the French should not be complacent. No country scored especially high on this measure, with the European average coming in at six out of 10. The message for politicians here seems to be that while reform may initially sound unpalatable to voters, it is the only game in town.

Conclusion. European health care systems are living on borrowed time. An aging population, the rising costs of medical technology and more demanding customers have produced chronic under-funding, which will only worsen as time goes on. Unless European health systems are reformed rapidly and decisively, the consequences will be dire: longer waiting lists, much stricter rationing decisions, discontented medical staff fleeing the profession, a decline in pharmaceutical innovation and, worst of all, more ill-health for Europe’s patients.

Across the board Europe’s politicians are struggling with a common set of problems. U.S. policymakers would do well to study not just the current failings of European health systems, but those countries’ long-term prospects before policymakers decide to use Europe as a model for reform.

End Notes

- Under a “mixed provision,” some health care providers are state-owned, some are run by private companies and some by voluntary bodies. Also, the funding may be a mix of a state-funded basic package, plus private co-payments.

- “European Health Consumer Index,” http://www.healthpowerhouse.com/media/EHCI2006.pdf

- For “Impatient for Change,” go to http://www.stockholm-network.org/downloads/publications/d41d8cd9-Impatient FINAL.pdf: for “Poles Apart” go to http://www.stockholm-network.org/downloads/publications/6d68025a-poles_apart.pdf

Helen Disney is the director of the Stockholm Network.

__________________________________________

Germany: How Not to Organize a Health Care System

By Wilfried Prewo

When we enter a department store or supermarket, the customer is king. We pick and choose according to our needs, tastes and budget. This is how free markets work: the customer makes his choice and pays accordingly.

Now suppose that instead of the traditional supermarket layout with the cashier at the exit, customers buy a ticket at the entrance and the ticket price is based on what they earn. Ticket in hand, they are free to roam the aisles and choose and carry away whatever they wish; nobody controls them. This new concept could be advertised as: “Buy a ticket to loot!”

This supermarket design is similar to the German public health care system that covers abo ut 90 percent of Germans.

Pricing in the Public System. Germans in the public system do not pay an actuarially calculated health insurance premium, but a payroll tax, currently 14.2 percent of their salaries up to a taxable limit o n earnings of €42,750 per year (US$54,164).1 This process caps the monthly payroll tax at €506 ($641), with the average being €241 ($305).

Slightly more than half of the payroll tax (7.5 percent) is paid by the employee, withheld from the paycheck. The remainder (6.6 percen t) is paid by the employer, raising the indirect cost of labor. Non-working spouses and children are covered free, whereas both husband and wife pay if both are working. 2

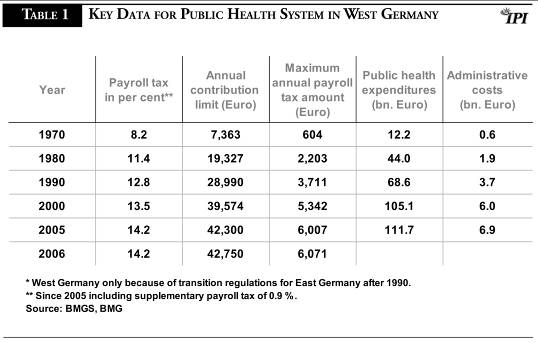

People in the public plan sign up for one of about 250 Krankenkassen (sickness funds). 3 By federal mandate, each sickness fund sets the payroll tax for its membership; but since all sickness funds must offer the same basic benefits package, competition among them is limited to minor deviations of the payroll tax around the national average of 14.2 percent. 4 Payroll tax increases occur frequently, having risen from 8.2 percent in 1970 to 12.5 percent in 1991 (united Germany) and then to 14.2 percent in 2006 (see Table 1).

Access to Care. The quality of care in the German system is good. Patients are free to choose their doctors, and waiting lists for surgeries are short. The system is not nearly as restrictive as, for example, the British National Health Service, where people can be denied services depending on their age, and long waits are common.

In Germany, an 85-year-old will not be denied a new hip. Of course, this is reflected in health expenditures. In Europe, only the Swiss spend more on health care, both per capita and as a ratio of GDP (UK: $2,546 per capita, 8.3 percent of GDP; Germany: $3,005, 10.9 percent; Switzerland: $4,077, 11.6 percent; all figures for 2003/2004). 5

All in all, Germans are satisfied with their health system, and other countries have even looked to the German system as a model. 6

The Role of Germany’s Private System. The main reason why the standard of care in Germany is considered satisfactory is not because of the intrinsic quality of the public system, with its 90 percent market share. Rather, the driver for high quality is the competition with private insurance.

Germans making more than €47,250 (US$59,866) can opt out of the public system and obtain private insurance. 7 The self-employed and civil servants (police and teachers, for example) can also opt out of the public system regardless of their salary level. A ll in all, about 20 percent of Germans can opt out of the public system, and half of them do. The other half typically are people whose income level did not exceed the opt-out level until they were older, or people with co-insured dependents; the private premium would then no longer be attractive. 8 However, for younger people and those without dependents, or for dual-income couples, the private insurance premium is in general lower than the payroll tax. More important, private insurance offers better coverage.

Even though it only has a 10 percent market share, private insurance is a highly effective competitive fringe. 9 Its lower premiums and better service attract the young high-income earners. Since this group typically also has low health expenditures, the public system is threatened by the loss of its most profitable clients. It can only keep them by not letting the service gap become too wide.

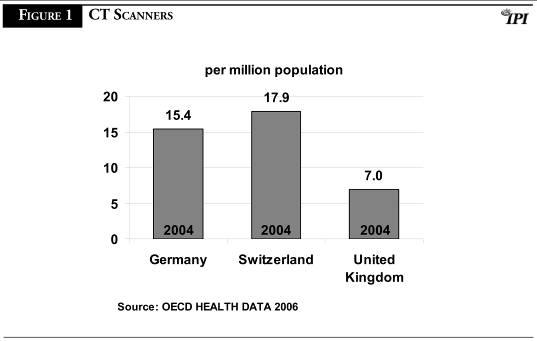

For example, 15 years ago, computer tomography was only covered by the public system in exceptional circumstances, whereas the private system covered its use for even routine diagnosis. Under competitive pressure, the public system added CT scanners. When complaints of a service gap get louder, the public system, fearing the loss of high-income and low-cost members, is forced to expand its coverage. Then the public system can negotiate lower fees, because it can argue that the investment is already considered a sunk cost. 10

In this way the private system in effect finances the introduction of a new tec hnology. It is estimated that the German private health system subsidizes the public system to the tune of €8.5 billion, or about 7 percent of its cost.

Due to this pioneering role of the private system, there is faster and higher penetration of new medi cal technology in Germany when compared with pure public systems such as the UK’s NHS (see Figure 1). In turn, better coverage means higher satisfaction, but it also makes the German public system more expensive.

As in most countries, health care expenditures in Germany have been rising above the rate of inflation. In 1980, health expenditures in the public system were €43.9 billion, rising to €77.5 billion by 1991 (West Germany). For united Germany they were €88.7 billion in 1991, rising to €134.9 billion by 2005. This represents an increase of 52 percent between 1991 and 2005, or 3 percent on average per annum—50 percent more than the rate of inflation during that period.

What’s Wrong with the German System and Why. The German government and business commu nity have become increasingly concerned about the payroll tax because it raises labor costs and makes German labor uncompetitive compared to low-wage countries. The high German unemployment rate of about 8.1 percent underlines this. 11

Over the last 30 years, one reform has followed the other, all with the goal of reducing health care expenditures and keeping the payroll tax from rising. None of these reforms achieved that, which is no surprise.

The fallacy of the welfare state is that the admirable goals of equity and universal access to health care are believed to require a unitary, standardized plan. Universal health coverage can be guaranteed only if it is publicly provided, the thinking goes.

But consider: Clothing, housing and food also fill basic needs. We do not want anyone to be without clothes, shelter or food. Yet those sectors are organized differently from health care. We do not have the government outfitter that issues the one-size-fits-all coat. We do not have the central quartermaster who provides standardized housing. Nor do we eat the same menu in the people’s canteen. For all these very basic needs, we let the market do the trick—and, as a society, we help the poor who cannot pay market prices so they can at least enjoy a minimum level.

Yet in the case of health care, many still believe that the goal of universal access requires a unitary plan with standardized benefits. In the German public health system, people cannot pick a lesser plan for a lower premium—such as a higher deductible or co-payment—in exchange for a lower premium, or choose less dental coverage in exchange for other options.

Getting the Incentives Right and the Reforms Wrong. A system that does not reward prudent restraint puts itself under permanent pressure because more and more will inevitably be demanded of it. In the face of unlimited demand, government should give individuals the freedom to choose among a wide range of health plans, from a minimum plan covering catastrophic health expenditures to fully comprehensive plans. At the same time, tax subsidies or vouchers would ensure the poor would also receive good health care. 12

Rather than following this bottom-up approach of empowering the consumer and letting him make choices, German health reforms have favored the top-down, interventionist approach. As the operator of the health supermarket, government never thought of moving the cashier from the entrance, and when the store ran out of money, suppliers were told they would have to restock empty shelves and, regardless of consumption, would only be paid a fixed sum per year (budget caps for doctors, hospitals and pharmaceuticals); access to the prized delicatessen (patented drugs) was restricted; sales consultants (pharmacists) were told to steer shoppers from beef to sausage as a cheaper alternative (aut idem rule); and all shoppers had to shoulder a minor co-pay that was tied to the volume, not value of what they took. They did not receive a discount in return.

The reforms originally took the form of seemingly moderate interventions, but have put Germany on the slippery slope towards socialized medicine. As reforms failed, the government stepped up the degree of command-and-control. The competitive fringe of private insurance still exists, but has now come under attack and may be undermined in the upcoming 2007 reform.

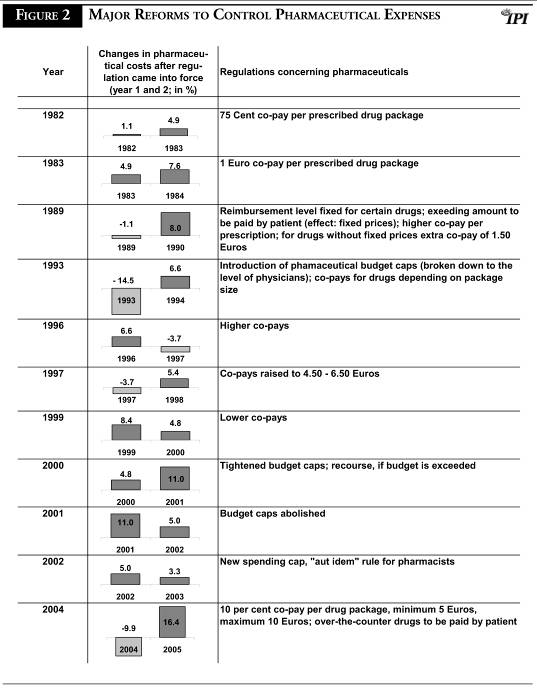

As an example of the effectiveness of past reform, we can look at the 11 major reforms since 1980 directed at lowering pharmaceutical expenditure (see Figure 2). The diagnosis is devastating: none of the 11 had any impact on expenditures after the first year. Seven out of 11 did not even have a positive impact on cost in the first year, and even in the four cases that showed a cost decrease in year one, this vanished in year two, often accompanied by above-average cost increases. 1

3

Some Lessons from Germany. The German health reform experience sadly shows that:

- There is stubborn refusal to adopt consumer-directed health reform, such as voluntary co-pays and deductibles, even though other countries (such as Switzerland) have shown their effectiveness.

- The failure of top-down, interventionist policies has been followed by an ever-higher degree of command-and-control.

- As reform fails, guilt is used to justify further interventionist steps. Doctors and pharmacists are held in high esteem and therefore spared; but their anonymous organizations or pharmaceutical companies and private insurance are singled out as villains.

- Top-down reforms consisting of budget caps, price controls and mandatory rather than voluntary co-pays yield no lasting impact.

The last point deserves further comment. In the case of centralized health care, patients or care providers will try to find ways to work around onerous measures in order to minimize their sacrifice. The fact that, in the German reforms, the cost-dampening effects never materialized or were at best of a temporary nature and evaporated after a year shows that patients and providers find out fast how to work around them. This is no surprise. A dictate is a singular policy, and the learning curve for working around them can be steep and short.

The Difference Consumers Make. The learning curve in the case of a consumer-directed measure is quite different, flat at first: Patients and providers will also seek to optimize their gain. But given options to choose from instead of a singular solution, this takes longer, since they have to understand and weigh the alternatives before deciding on the one best for them.

Often, they wait until others go ahead and then learn from their experience. Therefore, market-driven policies often have only a moderate immediate impact; the real impact unfolds in the medium and long term. They require patience—which may be one reason why politicians are hesitant to rely on them.

An example is the introduction of private pension accounts in Germany (Riester-Rente) that, despite generous government subsidies, were off to a slow start in the first year and were then, prematurely, considered a failure; now, they are one of the hottest selling pension products.

Likewise, in the United States, Health Savings Accounts did not march to the top of the charts immediately after introduction in January of 2004, but are continuing to grow in popularity. This suggests that thorough information and better dissemination of information can help consumers to move up the learning curve faster, pointing to what might be an effective role for government in the health care system.

End Notes

- At exchange rate of $1.267 per 1 Euro.

- Pensioners pay the payroll tax on the basis of their pensions; for the unemployed, the unemployment agency pays the payroll tax based on unemployment benefits.

- There were 253 sickness funds as of July 2006, reduced from 1,209 in 1991; more mergers are expected.

- The payroll taxes in 2006 vary from 12.7 to 15.5 percent. The differences reflect age and income differences, substantial differences in administrative costs, and also divergencies in the risk structures (morbidity etc.) of the insurance pools to the extent that a risk equalization scheme does not fully adjust for that. Members can switch funds every 18 months or whenever rates are raised.

- U.S. dollars at purchasing power parities; source: OECD Health Data 2006.

- The Clinton health plan of 1993/1994 was, essentially, a copy of the German plan. Fortunately, some people took a closer look and were able to dispel the myth.

- Originally, the opt-out income level was identical to the contribution limit for the health payroll tax that itself was set at 75 percent of the contribution limit for the pension payroll tax. The opt-out limit had been raised in order to make it more difficult to leave the public system. Since private insurance charges an actuarially calculated premium, age and number of insured dependents are important factors. With the contribution limit at its current level, not many young and single people can opt now.

- Once an insured has opted out for private insurance, he cannot return to the public system, making young people planning for a family hesitant to leave the public system.

- Fringe competition is especially forceful when the elasticity of substitution is high, as is the case here for those qualified to opt out of the public system. Market share alone does not confer monopoly power.

- There are many other examples that demonstrate that it is the fringe competition from the private side that drives quality improvements in the German public health system. The German public, however, is not concerned about the underlying causes; they are content when the public system’s coverage level does not fall too much behind the private system and notions of “two-class medicine” are kept in check.

- OECD, July 2006.

- For a reform proposal based on savings accounts concepts, see Wilfried Prewo, “From Welfare State to Social State,” Centre for the New Europe, Brussels, 2004. www.cne.org

- The 1997 decrease cannot be counted as a second-year benefit of the 1996 reform; it is the first-year effect of the 1997 reform. Alternatively, one could look at all health reform measures, not only those directed at pharmaceuticals, and contrast them against total health expenditures. But this yields an even harsher judgment. We think it is better to restrict the comparison to one segment of health expenditures, pharmaceuticals, because measures to cut total health expenditures could be outweighed by other, cost-increasing developments unconnected to policy.

Wilfried Prewo is the CEO of Hannover Chamber of Industry and Commerce

and a board member of the Centre for the New Europe.

_______________________________________________

Britain: Determined to Depend Solely on Tax Funding

By Stephen Pollard

There are two ways of looking at the Labour government’s reforms to the National Health Service: the glass is either half full or half empty. To take the glass-half-full approach, reform has been bold and far in excess of anything imagined even under the Conservatives.

The largest NHS union, Unison, has just organized a one-day strike by workers employed in NHS Logistics, the (state-run) organization that is responsible for, as it describes itself, “the physical supply of goods required for health care.” Its workers are outraged that the government has announced that a 10-year contract for such work has been awarded to a private firm, DHL. As the union’s head of health, Karen Jennings, put it, “Staff across the NHS will be watching this privatization deal, which will be viewed by many as symbolic of what is to come.”

One can but hope.

The Evolution of the NHS. After nearly 10 years of Labour government, it is easy to forget just how much things have changed. When Labour first took office, its then-Health Secretary, Frank Dobson, pledged to abolish the Conservatives’ internal market reforms.

His first policy statement did not even mention the private sector. He forbade local NHS authorities from cooperating with the private sector other than in the most straitened circumstances. And he went out of his way to demonize any health care not provided through and by the state. (Some parts of the NHS had, for historical reasons, always been privately provided, such as opticians, pharmacists, general practice and some specialist mental health services. Labour had no plans to turn that clock back.)

With his departure, the new Health Secretary, Alan Milburn, took a more realistic and less ideological approach. The publication of the NHS Plan in July 2000 was, in this context, revolutionary.

Indeed, his agreement of a “Concordat” with the private sector, which was explicit about the need for cooperation between the two sectors, was unprecedented in NHS politics. Even Baroness Thatcher had shied away from contracting out the provision of services to private providers. Milburn, however, took the view that where the NHS was incapable of meeting demand, it should turn to private suppliers.

The change in policy was driven more by failure than any great intellectual conversion. That, such as it was, came later. Labour had been elected on a pledge to cut waiting lists and waiting times. But they were, for many areas, rising. In desperation, the government turned to the private sector.

Enter the Private Sector. But all of this was still about utilizing spare capacity in the private sector—a common sense arrangement which only the most ideologically driven could oppose. Using spare capacity in the private sector was one thing; building new private capacity, for the NHS’s use, was, however, quite another.

That further shift occurred in 2002, when a capacity-planning exercise by the Department of Health showed the need for faster treatment and greater supply in areas such as cataract and hip replacement surgery, where there were still long waits. The decision was taken to open up the tendering for the provision of new units, to be called Diagnostic and Treatment Centres, to the private sector. The first privately run treatment centre opened in October 2003. To date, 34 such contracts have been awarded.

In effect, the story of Labour’s health policy has been a giant step backwards, followed by years spent returning to the status quo ante of 1997, followed by ever-greater contracting out of services to the private sector.

Private provision is, however, responsible for only a tiny proportion of the NHS’s output. The latest figures (to mid-2005) show that so far just 16,000 patients have been treated in private-sector treatment centers out of a total of some 5.5 million non-emergency operations. That said, so far the government has contracted with the independent sector to do a future 460,000 operations, and the trend is clearly towards still greater expansion. In February 2005, for example, diagnostic services worth £1 billion were put out to bid.

Reliance Solely on Tax Funding. There is, however, a “glass half-empty” view which is, I would argue, even more compelling than the ‘half-full’ analysis. Labour’s policy amounts to spending as much money as it possibly can, making the delivery of NHS services more efficient through contracting out many aspects, and…er, that’s it. Labour remains wholly committed to an exclusively tax-funded health care system, explicitly ruling out any other method.

Tony Blair, for instance, is as pro-market, pro-choice and pro-profit as any Labour leader could conceivably be, but when it comes to the provision of health care, he is in many senses as antediluvian as any of his Labour colleagues.

Blair’s belief is as solid as his likely successor, Gordon Brown’s—that not only is tax funded health care the only truly efficient form of funding; it is also the most, if not the only, morally decent basis for the provision of services.

In a seminal speech in 2003 to the Cass Business School, Brown outlined just this view, arguing that it was not merely funding which should be provided through the state, but provision, too: “The very same reason which leads us to the case for public funding of health care on efficiency as well as equity grounds a In a seminal speech in 2003 to the Cass Business School, Brown outlined just this view, arguing that it was not merely funding which should be provided through the state, but provision, too: “The very same reason which leads us to the case for public funding of health care on efficiency as well as equity grounds also leads us to the case for public provision of health care.”

So when Mr. Brown, amidst a great hoo-ha, set up an inquiry designed, as its terms of reference put it, to “identify the key factors which will determine the financial and other resources required to ensure that the NHS can provide a publicly funded, comprehensive, high quality service,” it found that—quelle surprise—only the NHS model was capable of providing a publicly funded, comprehensive, high quality service. As the then Leader of the Opposition put it in response: ask a Labour question and you get a Labour answer.

The inquiry found that “no other system would deliver a given amount of care cheaper.” That is a moot point. But it is, more importantly, also the wrong point—which is to have a system that is capable of delivering the amount of care which is demanded and for which people are prepared to pay.

Spending Spree. Labour began its spending spree in January 2000 with an announcement by Tony Blair on a breakfast TV interview that UK state health spending would rise to the European Union average. But the rationale behind this was misconceived. By the end of the first slice of extra spending, in 2003-4, health spending in Britain had indeed risen, to 7.6 percent of GDP, compared with an EU average of 8.9 percent.

But in terms of spending on health care financed through taxation, Britain was anyway spending almost the same (about 0.1 percent of GDP less) as its EU neighbors. The reason why the total level of health care spending in Britain was 1.3 percent of GDP less than in its EU neighbors was that where private spending in Britain is negligible, elsewhere in the EU it is substantial. So Labour was committing itself to spending vast sums of tax revenue to bridge a shortfall which elsewhere was accounted for by private spending.

But Labour had already ruled out from the start anything which addressed the real question: Should Britain do what the majority of European systems did not, and close that spending gap by increasing taxes to pay for the ever-greater amounts of public money which would be needed to do so? Or was there a better way to fund—and run—a health system than taxation alone?

Lessons from Britain. The best way of thinking about Labour’s health care policies is as a controlled experiment. For the first time, the NHS has been getting the money its defenders have always said it needed to work (although that is a moving target, since even with the new levels of spending—way in excess of anything that was ever demanded by the NHS boosters—the argument continues that it is underfunded).

At vast expense to taxpayers, the UK has been testing—perhaps to financial destruction—the ideological starting point that tax funding is the critical element in an efficient health care system.

The figures suggest that the answer is clear. As the think tank Reform puts it:

-

-

Spending on the NHS has increased at an unprecedented level—doubling since 1997 (in cash terms) and due to increase a further third by 2008—but on all appropriate measures productivity has declined. The Prime Minister’s Strategy Unit and the OECD have both found falling productivity of up to 20 per cent since 1997. …The Office of National Statistics produced new figures in 2004 which confirmed falling productivity of up to 1 percent per year since 1997. The new estimate drew on 1,700 different categories of NHS output, covering over three-quarters of all NHS activity.

Conclusion. The lesson for U.S. reformers is clear. Do not listen to the perennial siren voices which call for a single-payer system in the U.S. It would be the ultimate irony if, at the very time when a Labour government is doing its best to grapple with the deleterious consequences of such a system in the UK—even if, for ideological reasons, it will not ditch the basic principle of exclusive tax funding—the U.S. were to embrace such a fundamentally flawed model.

Stephen Pollard is a senior fellow at the Centre for the New Europe, in Brussels, where he runs the Health Unit.

______________________________________________________

Swiss Health Care: A Clockwork Model that Fails to Keep Promises

By Alphonse Crespo, M.D.

Switzerland’s pluralist social health care system stems from constitutional articles voted in 1890 guaranteeing access to adequate health care for all. This goal was achieved by a delicate blend of social insurance, private enterprise, oligopoly and competition in which the government played a subsidiary role and where wide autonomy was left to the cantons. Limited government intrusion, strong and innovative health industries, reputable medical schools and a market economy spared by two world wars gave quality care to all levels of society for many decades.

The Promise Denied. But efforts for health care reform that began in 1960, pushed for an increased regulatory and redistributive function of the state. Social-democratic reformers finally got their way in 1994 with the creation of the Federal Law of Insurance against Sickness (LAMal), which established compulsory insurance and appointed insurance providers with wide regulatory powers.

These changes were supposed to increase the efficiency of care while at the same time controlling costs. LAMal entailed a shift of authority away from the cantons and towards federal policymakers. Switzerland’s current preoccupation with “EU-compatibility” has accelerated the trend towards central planning, regulation and control. Instead of improving the Swiss health care system, this has adversely affected costs and quality.

Expenditure, Financing and Resources. Switzerland spent 3.5 percent of GDP on health care in 1950.1 This percentage increased to 11.6 percent by 2004, significantly more than other major European countries and second only to the United States. The health sector employs more than 450,000 people and is currently worth some U.S. $40.4 billion.

Cantons and the federal government directly finance approximately 25 percent of total spending, social insurance covers 35 percent, and supplementary insurance and contributions from private institutions account for 10 percent. The rest is met from out-of-pocket payments.

After mandatory deductibles that range from U.S.$242 to U.S.$2,022 per year, depending on premium options, patients pay for 10 percent of ambulatory care costs. Parliament is considering raising this to 20 percent. Co-payments for original drugs have already been capped at 20 percent when equivalent generics are available. Co-payments for hospital care are being discussed.

Switzerland has about the same density of physicians and number of acute hospital beds per capita as its neighbors. In 2001, however, it counted more MRI scanners per million inhabitants (12.9/million) than France (2.6/million) or the U.S. (8.1/million), but trailed Japan (23.2/million). 2

The private hospital sector, open to citizens with supplementary insurance or to wealthy foreign patients, remains very active and offered 0.7 beds per 1000 population in 2000 (an increase of 17 percent from 1998). Compared to other European nations, Switzerland still provides a high standard of care. Health policy planners contend, however, that the Swiss system has too many hospitals, doctors and equipment.

The Hospital Sector. Hospitals are evenly financed by basic insurance and government subsidies. Parliament is currently discussing a single-payer model, i.e., either government or insurance. Withdrawal of state financing rarely implies withdrawal of state control; privatization of public hospitals is not part of the agenda.

Between 1998 and 2000, the number of public hospital beds was hammered down by 6 percent through forced mergers of regional hospitals, closure of acute care units and the centralization of high technology. The downgrading of regional hospitals creates inequities in access to care. Patients from small towns or from alpine valleys are often bounced from one local hospital to another before receiving appropriate care. In many instances, ambulances have come to replace elevators as a means of transfer from one specialty unit to another. Waiting lists for surgery in university hospitals also have increased.

Regulators have targeted average lengths of stay in acute care hospitals. These have been cut down from 12.9 days in 2000 to 9 days in 2004. 3 Present reimbursement scales encourage outpatient surgery despite higher risks and lower patient comfort, while low fees for demanding procedures (linked to longer stays in the hospital) dissuade surgeons from performing heavy elective surgery.

Some local health authorities have begun to outsource surgery to neighbouring countries. This attempt to confront local providers with “foreign competition” remains anecdotal and looks more like tapping into the subsidized resources of European neighbours than letting market competition enter the game.

The Physician Sector. Doctor density doubled between 1950 and 2000. Switzerland now has approximately 25,000 doctors, 55 percent of whom are in private practice. In 2002, the federal government suspended the opening of private medical offices. This drastic measure circumvents constitutional rights, and stems from the erroneous assumption that costs are tied to the number of practicing physicians.

The Swiss Observatory of Healthcare demonstrated in 2002 that visits to doctors’ offices were unrelated to GP density. This has not stopped the federal authorities from extending the ban to 2008. All this achieves is shifting primary care from doctors’ offices to costlier public hospitals.

In 2004, after long negotiations between the medical professional association (FMH) and the insurance cartel, cantonal fee rates were replaced by a unified time-based fee scale (TARMED) designed to upgrade “intellectual work.” The “neutrality of costs” clause that was part of the deal involved drastic downgrading of fees for technical procedures. The new tariff has had no effects other than to create:

- Recurrent haggling between doctors, doctor associations, hospital administrators and third-party payers;

- Longer waiting lists for more complex elective surgery linked to fees that barely meet overhead; and

- Bewildered patients who are now charged by the minute for “intellectual services” that inevitably include small talk.

Repeated exposure to strong-armed regulatory measures has sapped the morale of the medical profession. Their frustrations climaxed in an unprecedented demonstration that brought 12,000 protesting doctors onto the streets of Bern early in 2006.

The Pharmaceutical Sector. The inter-cantonal regulatory body in charge of certifiying pharmaceutical products (OICM) and the Unit for Therapeutic Agents from the Federal Office for Public Health, fused in 2002 to create Swissmedic. This central agency for therapeutic products is entrusted with tasks that range from the certification of condoms to drafting laws and standards of surveillance and closely follows norms set by the European Economic Commission bureaucracies.

Incentives designed to push the prescription of generics at the expense of brand name drugs have lowered spending on medication. The sale of generics increased by more than 55 percent during the first semester of 2006, worth some U.S.$205 million. This effort is hurting pharmaceutical industries that invest in research. The trend will predictably affect the development of new drugs, slow down advances in curative medicine and ultimately increase the costs generated by disease.

Possibilities for Reform. Political reform in Switzerland hinges on a complex consultation process aimed at consensus. The dice in health care, however, are heavily loaded. 4 A substantial number of parliamentarians are linked to the administration of social insurance funds and weigh heavily on the decision-making process. Doris Leuthard, former president of the Christian-Democratic party and a prominent member of the board of directors of Switzerland’s second largest sickness fund, is Switzerland’s new Minister of the Economy. In contrast, there are currently no more than five practicing physicians in Parliament, two of whom come from socialist and communist factions.

A constitutional initiative launched in 2004 by trade unions and the socialist party called for a single national insurance provider and for insurance premiums pegged to personal income. This proposal that would abolish some 90 existing sickness funds was rejected by Parliament, but the issue will be taken to referendum vote in 2007. Deep public dissatisfaction with sickness funds and current polls reflect a readiness to accept a single insurance provider as a lesser evil.

Assessment of the Swiss System Today. Despite Swiss meticulousness, regulation has failed to live up to expectations.

- It has not curbed costs;

- Health insurance premiums have become a burden for most families; and

- Cost containment measures have constricted hospital infrastructure and constrained medical activity with worrisome effects on quality and accessibility.

Since 1890, Switzerland has incrementally moved health care away from the market. This process, however, is no longer working and its rhetoric is becoming as exhausted as its purse. Terms such as “competition” or “freedom to contract” are no longer taboo, even though they are still severely misused.

Although they cannot match the boosts to innovation that would come from lighter regulation, partnerships between public institutions and private industry are stimulating research. Recent policy suggestions aimed at separating health care (to be left to the free market) from sickness care (where government intervention is deemed desirable) open new inroads. 5 Federal Health Minister Pascal Couchepin now recognizes that the health care sector creates jobs, that its growth responds to the evolution of modern society and that its costs should be seen as investments!

Conclusion. The belief that government can fix fundamental flaws in regulated health care systems has yet to come to terms with reality. Copying the failing social experiments from Europe or Canada will not help the United States. Health Saving Accounts, risk related insurance, voluntary pooling and private or corporate philanthropy will address sickness care far more efficiently and adequately than any system based on public financing and bureaucratic regulation. Yet such laissez-faire solutions remain anathema to most health care policymakers. This is not surprising. While a truly free market enhances autonomy and personal responsibility, it also reduces waste and drives bureaucracies out of business.

End Notes

- See G.Kocher, Willy Oggier (2005) Système de santé Suisse 2004-2006 – Survol de la situation actuelle Verlag Hans Huber, pp105-109.

- G.Kocher, Willy Oggier (2005) Système de santé Suisse 2004-2006 – Survol de la situation actuelle Verlag Hans Huber, pp 85-87.

- Office Federal de la Statistique, Statistique Médicale 2004.

- B.Kiefer, Bloc-notes: Derrière le sourire de Doris, Revue Médicale Suisse, No 3071, 2006.

- L’Avenir du Marché de la Santé, Etude élaborée par S.Sigrist, Gottleib Duttweiler Institute sur mandat du Departement fédéral de l’interieur, Berne, aout 2006.

Dr. Alphonse Crespo is a research director of the Institut Constant de Rebecque in Lausanne, Switzerland.

_______________________________________________

Sweden: Losing Faith in Top-Down Regulation

By Fredrik Erixon

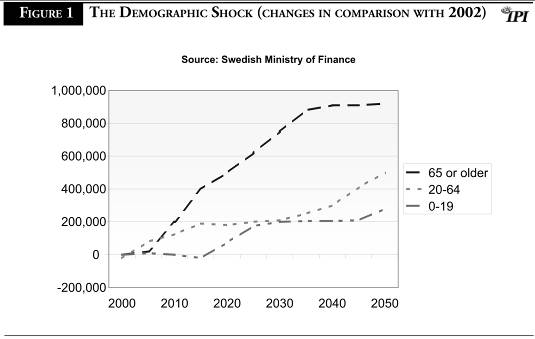

As in every other country in the developed world, health care expenditure in Sweden has increased rapidly in recent years. In real terms, health spending rose by 4.2 percent per year in the last five years; estimates suggest even faster growth in expenditures in the next decades, primarily due to demographic changes and technological factors.

- People are living longer (and require more health care);

- The dependency ratio is deteriorating (Sweden already has a significantly higher share of the population above age 80 than other OECD countries, and the ratio will increase even further in the next two decades); and

- Technological developments are expanding the range and quality of available treatment.

Combine these with today’s more demanding health care consumer, and the upward pressure on costs is irresistible.

Getting Older Is Good, but Expensive. Figure 1 illustrates future demographic change in Sweden: In 15 years the number of people above the age of 65 will have grown by nearly 500,000, while the number of people of working age will grow by less than 200,000. Because of Sweden’s expensive system for caring for seniors, annual expenditure growth is likely to be above 6 percent from 2010 to 2020.

This is all very bad news for Sweden’s fiscal well-being. Swedish health care is a top-down, bureaucratic system that lives and breathes through the cost containment and rationing paradigm. It is a model that bears little resemblance to a normal market. That is why the system fears increasing life expectancy, even though it is obviously a good thing for the population.

The Top-Down Regulatory Model. The policy ambitions of the Swedish health care model are many. It aims to deliver the best available health care to all. In addition, Swedish politicians view the health care system as a tool of industrial policy, hoping that it will stimulate domestic investment in pharmaceutical and health technology research.

To fulfil these ambitions, the health care system is modelled on the following assumptions:

- Health care is planned by politically controlled bodies and largely carried out by publicly owned hospitals and health care centers.

- Health care is mainly funded by the government. Private funding—by private insurers or out-of-pocket spending—accounts for a small part of total health expenditures. According to OECD estimates, 85 to 90 percent of all health expenditures are financed by taxes.

- Drugs are also funded by taxes. The Pharmaceutical Benefits Board, a political body, decides (based on health technology assessments) whether a particular medicine should be publicly reimbursed, and drugs (including non-prescription drugs such as aspirin) can only be purchased by patients in government-monopoly pharmacies.

In addition, Sweden is a great proponent of the potential of what is termed parallel trade (in other words, allowing or encouraging drug imports) to control spending on drugs. Prior to joining the European Union in 1995, Sweden allowed drug imports from all countries in the world, but now follows the EU regime of importing only from other EU countries.

This highly regulated and socialistic health care model is probably not surprising to an international observer. No country in the world has a higher tax burden than Sweden, and health care spending is one of the central features of most welfare states.

What is surprising, however, is that most Swedish observers, including the public sector trade unions, have essentially lost faith in this model and do not believe it can survive in its current form. This development offers some salutary lessons to the United States as it debates the future of its own health care system.

The Problems of Excessive Regulation. The Swedish health care model suffers from several structural problems.

Most obviously, it no longer delivers what it promises. It is difficult to get access to a doctor, especially if a patient has a condition that requires treatment by a specialist.

In a single-payer system based on taxes, there is a clear limit to the performance of health care. Health care supply is determined by available resources, and if the demand exceeds supply, patients will have to wait.

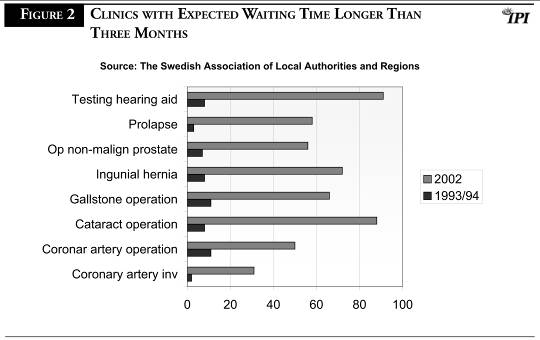

Figure 2 shows how this situation has worsened in Sweden. Now, fewer clinics are able to treat patients within three months, which is the state-defined limit, than in the early 1990s. In the early 1990s, 70 percent of clinics could perform a gallstone operation within three months; in 2002 only 10 percent could manage this.

These delays have a negative effect on fiscal policy: the longer a patient needs to queue for treatment, the longer the patient receives sickness benefits. These costs are often neglected in comparisons of health expenditures between countries.

Longer queues are only one symptom of the need to ration health care; an equally serious problem, economically and morally, is rationing of the kinds of treatments that can be paid for by taxes. As costs have increased, several County Councils, the organizational level of Swedish health care, have stopped financing treatments for non-malignant cancer and haemorrhoids, for example, unless the patient can pay out of pocket.

It is true that not all of these conditions are fatal, and it is a reasonable principle that taxes should not finance all health care. But is a system fair when it is effectively impossible to pay for additional health care insurance that can cover additional expenses? The only way to pay for it is out of pocket; in a country where one-third of the population lacks any savings at all, this implies a very inequitable health care system.

Second, the Swedish health care system is extremely unproductive. The number of doctors grew by 175 percent between 1975 and 2000, but during the same time the number of consultations per doctor per year declined from 2,024 to 909. A small part of this decline is explained by an increase of treatments that demand more of the physician’s time, but the vast majority of the fall in productivity is due to an increasingly inefficient use of doctors. This trend continues. Measured as DRG per employee, labor productivity in public hospitals fell by 20 percent between 1998 and 2003. 1

Third, the Swedish system is increasingly unable to pay for new medicines and new health care technology. As in most other OECD countries, the cost explosion in Swedish health care is often explained by increasing expenditures on medicines. It is true that the total cost for medicines has risen, but increasing total health care expenditures have very little to do with pharmaceuticals. The deterioration is rather explained by falling productivity and an organization of production that is increasingly occupied by bureaucracy and less by patient consultations.

Steps Toward Reform. The Swedish health care sector is in need of reform. Actually, reforms have already started, but most proceed much too slowly. However, some reforms have improved health care significantly.

Many primary health care centers have been privatized and are much more productive than the public health care centers. Some hospitals, primarily in the Stockholm and Gothenburg regions, have also been privatized with the same result. Despite getting less compensation per case, these hospitals produce more health care than public hospitals and are the only hospitals in Sweden where productivity has improved. Such changes in the organization of production are bound to continue in the next decade.

It is also obvious that future increases in health care expenditures must come from other sources than taxes. If Sweden continues with current policies, fewer treatments will be covered by the public health care insurance and the comparative quality of health care will further deteriorate.

The financing of health care is also associated with Sweden’s industrial ambitions. Sweden is still home to several pharmaceutical and biotech companies. Pharmaceutical exports have increased rapidly in recent years, and Sweden generally performs better than other European countries in terms of research, innovation and patents.

But Sweden is losing ground here as well. Highly innovative phases in research and development of new medicines, for example, are increasingly moving abroad. As in many other European countries, the emigration of innovation is partly due to a lack of funding in the health care system; companies are less inclined to stay at home if their new products cannot be introduced in the market because they are too expensive for the health care system.

Some in Sweden believe increased parallel trade is a “magic bullet” that will solve our health care funding problems. But no serious observer believes this to be the case. The cost explosion is mainly due to deteriorating productivity and the organization of health care production.

Furthermore, Sweden already imports parallel-traded medicines from the southern member states of the EU—primarily Greece, Spain Furthermore, Sweden already imports parallel-traded medicines from the southern member states of the EU—primarily Greece, Spain and France. The market value for parallel-traded imports, as a share of the total pharmaceutical market, is nearly 12 percent (up from 1.9 percent in 1997), but the effect on prices has been minimal.

Conclusion. Sweden is taking steps toward expanding private sector options in health care delivery. Progress is slow, but it’s a start. However, the pharmaceuticals sector has been marginalized because of price controls, and has a long way to go if Sweden wants to wants to turn it into an economic powerhouse.

End Note

1. Diagnosis related groups (DRG) is a system for compensating hospitals for their work. Every treatment is categorised in a DRG and the County Council allocates a specific compensation for every DRG point produced by a hospital.

Fredrik Erixon is the director of the European Centre for International Political Economy.

____________________________________________

Why Canadians Pay Less for Drugs than Americans

By Brian Lee Crowley

The prices of patented (that is, brand-name) prescription drugs usually are lower in Canada than in the United States. Many people think the reason is price controls. While price controls do have a role, that role is largely marginal compared to other factors, especially differences in standards of living between the two countries and legal liability issues. 1

How Government Prices Drugs. The prices for patented medicines (broadly defined as prescription pharmaceuticals) in Canada are controlled federally by the Patented Medicine Prices Review Board (PMPRB). It uses international price benchmarking to regulate Canadian prices, in effect creating price ceilings. The Canadian price for new products cannot be more than the average price of the seven international “peers” the PMPRB uses as the reference group. Although it is one of the wealthiest countries, in 2003 Canadian prices for patented medicines were about 5 percent below the international median.

There is reason to debate whether the ceilings are in fact binding, and whether prices would be any higher in the absence of regulation. More important, the PMPRB does not control the retail price of drugs. Rather, it regulates what has been called the “factory gate price” of drugs, the price the manufacturer charges the wholesaler at the first stage of the marketing chain. 2 The wholesale and retail markups are left to the market.3

This is not to say that government regulation is never the determining factor behind drug prices. It is widely accepted that Canadian pricing rules are the reason the prices of generic drugs are noticeably higher in Canada than they are in the U.S., where competition keeps prices lower. 4 While the price of patented drugs is generally higher in the U.S. than in the rest of the world, once drugs come off patent, American consumers generally get a better price than the rest of the world.

In addition to federally regulated prices, provincial governments, which deliver most health care services in Canada, have a number of policies that affect prices. All provinces provide drugs for a large share of their population, generally seniors and those on low incomes. Here the control mechanism revolves around the provincial formulary, the list of drugs approved for reimbursement by the province. Although people not covered by the provincial drug plans are free to buy outside the formulary, in practice being off the formulary means that a drug cannot really penetrate the provincial market to any significant extent. Moreover, the province will become a bulk purchaser of many of the drugs on the formulary (for hospitals, etc.), giving it extra leverage on cost.

Provinces negotiate hard with drug companies on the price they will reimburse before approving a medication for the formulary. This means that the negotiations on price are not normal market negotiations, because the provinces hold the “hammer” of controlling access to that essential listing on the provincial formulary. In Ontario, Canada’s largest province, a price freeze has been in effect since 1994 on pharmaceuticals on the formulary.

Thus the different forms of government intervention certainly play a role in the differences in drug costs between Canada and the U.S., but differences in standards of living between the two countries and legal liability issues play even larger roles.

Different Living Standards Mean Different Prices. The standard of living used to be quite comparable in the U.S. and Canada, but Canada’s has been falling relative to the U.S. for several years. Today the average Canadian has a standard of living that on some measurements is 20 to 30 percent lower than the average American. That variation has consequences for this discussion. To understand why, we have to talk about what economists call price discrimination.

Basically, firms sell their product in different markets, and charge different prices on the basis of local market conditions. When a firm sells its product in two different markets, so long as those markets are separate, the firm will calculate a unique profit-maximizing price for each market. The general rule is that the price will be higher in the market where consumers are less sensitive to prices (i.e., the amount they buy will be less influenced by the price they pay). Low-income markets tend to be more price-sensitive, so prices will tend to be lower in those markets, so long as separation of the markets can be maintained.

There is no doubt that one of the major explanations of drug price differentials between our two countries is market separation to reflect the fact that Canadians cannot pay as much as Americans for their drugs. From an economic point of view, this makes perfect sense. Every separate market will have a profit-maximizing price that represents that market’s maximum sustainable contribution to the R&D effort of the pharmaceutical industry, as well as covering the hard costs of producing the actual medicines consumed. 5

Note something very important: If a company is selling at a high price in a well-off market and a lower price in a less well-off market, and if separation of the markets ends so they find themselves having to charge the same price in both markets, both the company and at least one set of consumers will be made worse off as a result.

Problems with the U.S. Legal Systems. The last major factor that explains cross-border price differentials is the U.S. legal system. That system has a significant, and probably harmful, impact on the U.S. market for prescription drugs. Drug companies are favorite targets for American trial lawyers. Drug companies are not unique in this, of course. The entire U.S. health sector is a feeding ground for trial lawyers.

While the possibility exists to have jury trials in Canada for civil cases, they tend to be extremely rare, and judges tend to be more demanding on evidence and less forthcoming on “redistributive” damages than U.S. juries. The U.S. legal system in effect imposes a huge tax on pharmaceuticals that Canadians do not have to pay.

Richard Manning (1997) looked at the role played by American liability rulings on the difference in pharmaceutical prices between Canada and the United States. He concluded, “A large part of the observed variation in the price differential is attributable to anticipated liability cost, and liability effects explain virtually all the very big price differences observed. The best prediction of the model is that in this data set, liability risk roughly doubles the average price differential and increases the median price differential by about one-third.” 6

Rest assured that U.S. trial lawyers are clever and inventive enough to find a way to use the country’s legal system to impose some of those liability costs on Canadian suppliers of drugs that have crossed the border, with predictable effects on prices.

So the evidence shows that the price differential between Canada and the U.S. is driven chiefly by market forces (in the form of market separation) plus the costs of U.S. product liability policies. Canadian government price controls explain considerably less of the differential, but the precise proportions are a matter for further research.

The Hidden Cost of Government Regulation. But while almost all of the discussion about drug prices centers on how Canadians benefit over Americans, you should know that Canadians also pay a price—a big one.

One of the most important things to understand about the way pharmaceuticals work in Canada vs. the U.S. is not how government intervention influences pricing, but how it affects the behavior of the industry, investment and innovation. This is the great hidden cost of Canada’s system.

In a paper published in 2004 by Roger Martin of the University of Toronto and James Milway of the Institute for Competitiveness and Prosperity, the authors examined the biopharmaceutical sector in Toronto, which because of the presence of many high quality factors of production in that sector, should be a North American leader in R&D and innovation in pharmaceuticals. Instead it lags well behind its peers.

Why? The authors found that:

-

-

[O]n a per capita basis, Ontarians spend about three-quarters of their U.S. counterparts on drugs ($512 in Ontario v. $674 in the United States). While many applaud this, it represents a public policy choice. We have lower prices, but the lack of a sophisticated buying process means a less well developed cluster and reduced innovation and upgrading from our impressive factors conditions. The single dominant buyer in the process in Ontario differs from the process in the United States—one with multiple buyers who are both demanding and sophisticated as a result of the pressure placed upon them by the end consumer, who is more educated and has multiple choices of health care providers and a system that is less restrictive at the state level. 7

The outcome is that Canada produces pharmaceutical inventions at half the rate of the U.S., and Canada’s per capita investment in R&D is one of the lowest in the developed world. R&D investment in Canada grew 13.5 percent annually, compared to 32.5 percent in the U.S.

Meanwhile, average wages in Ontario’s biopharma cluster are 38 percent lower than in the largest U.S. states. Clearly, government’s role as a dominant buyer of drugs and, to a limited extent, price controls squeeze pharmaceutical company profitability. R&D and production activities will, in a globalized pharmaceutical industry, be transferred to the jurisdictions where the greatest post-tax profits can be generated, and that in turn generates investment in R&D effort that, in its turn, generates new discoveries, production, R&D and so forth. The U.S. has created a virtuous circle in this regard, Canada a vicious one.

Rationing by Regulation. Government procurement practices do not simply reduce price; dominant-buyer conditions also reduce availability of new products. To contain costs, government has implemented mechanisms to limit reimbursement of new drugs: restrictive drug formularies.

Ontario has one of the most restrictive provincial drug formularies, with only 35 percent of new drugs launched between 1997 and 2002, versus 59 percent of new drugs listed in Quebec, one of the least restrictive provinces. This is in spite of the fact that research shows that new drugs tend to be more effective and have fewer side effects on average than the older drugs that they displace. Further, the price freeze that has been in effect since 1994 not only limits industry revenue, but also affects prices for new products brought to market. By limiting the number of new innovative treatments that are reimbursed, the government’s “silo mentality” is in effect raising total health care expenditures by focusing solely on the price of the drug listed at the expense of the total cost of treatment per patient.