Introduction

The public and the government need to do something about the low rate of saving in the United States. The personal saving rate and the national saving rate in the United States are low by historical standards and are less than in many other major nations.

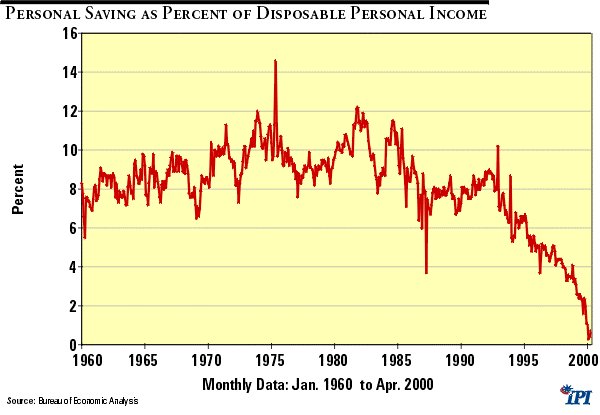

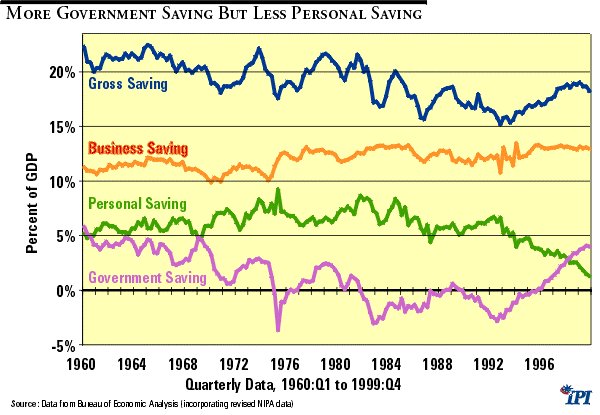

The personal saving rate (saving as a percent of “disposable” after-tax income) has plunged over the past 15 years, from about 9 percent in the mid-1980s to nearly zero in 2000. [See Figure 1] Baby boomers are fast approaching retirement with limited financial resources. Social Security faces insolvency, and cannot pick up the slack. Business saving has scarcely changed as a share of the economy, so total private saving has declined as a share of gross national product (GNP). The dearth of saving has restricted investment, considerably retarding the growth of productivity, wages, and employment, and slowing the growth of individual income and wealth.

Figure 1

This paper describes the saving situation, explores its causes, and suggests what might be done about it.

Importance of Saving

The level of saving in the United States is of concern for two main reasons: it affects the welfare of individuals and it affects the strength of the economy.

For individuals, saving is a way to boost income, protect against a rainy day, pay for their education and that of their children, buy a home, start a business and provide for retirement. Having sufficient assets to provide a comfortable retirement is becoming increasingly important. The Social Security system faces large deficits as the baby boom generation retires and increasing strain in the decades ahead. It is highly likely that some of the increases in Social Security benefits that are being promised to current workers will have to be scaled back. If private saving remains low, the outlook for a comfortable retirement is not good for millions of Americans.

With respect to the national economy, saving provides the financing for investment in physical capital (plant and equipment, commercial and residential buildings) and for research and development. Investment is absolutely essential for increasing the productivity of the work force and thereby raising wages and living standards over time. Higher levels of productivity would also make it easier for a relatively smaller work force to provide the real goods and services that will be needed by a relatively larger retired population in the years ahead.

Americans Lack Sufficient Assets for a Comfortable Retirement or Other Purposes

The Federal Reserve Board publishes the “Survey of Consumer Finances” every three years. The latest Survey, from 1998, suggests that Americans have increased their holdings of financial assets since 1995, due in part to the large rise in the stock market. Nonetheless, most Americans lack sufficient accumulated personal savings to provide significant income during their retirement years. Millions will have to work at least part time beyond age 65. Millions more will rely mainly on Social Security or employer-provided pensions unless they sharply increase their rate of saving in the years that remain before they retire.

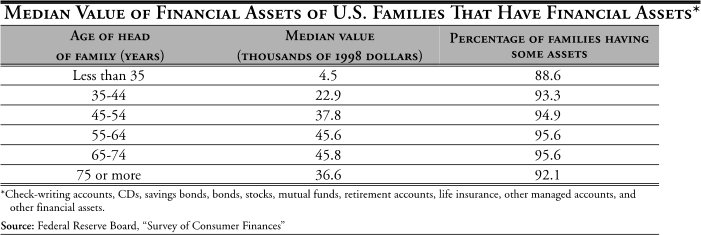

Table 1

American families whose heads were between ages 55 and 64 had financial assets with a median value of $45,600 in 1998. Families whose heads were between ages 65 and 74 had financial assets with a median value of $45,800. If we assume that families continue to save between ages 55 and 62 and that they begin to draw on their savings sometime between ages 62 and 65, these figures suggest that families headed by persons between ages 62 and 65 may have had a few thousand dollars more just at the point of retirement.

Since these are median figures, half of the families with assets had less than these values. Furthermore, these figures are for families that reported having some assets. While 95.6 percent of all families in these age groups reported having at least some savings, over 4 percent of the families surveyed reported having no financial assets at all.

According to the 2001 Social Security Trustees Report, Table III.B.5,1 single workers who earned the average wage most of their working lives could have retired in 2001 at age 65 with about $12,642 in annual Social Security benefits. A married couple with the spousal benefit would have received about $18,963. The Social Security benefit formula is set up to grant higher real retirement incomes to future retirees as real wages continue to climb, close to $18,477 for a single average wage worker and about $27,715 for a couple in 2030 (in 2001 dollars). However, the Social Security system is projected to begin running enormous deficits as the baby boom generation retires. Without a substantial payroll tax increase, which would make it harder for workers to save, the promised increases in real benefits will have to be scaled back.

Let us assume that an average-wage baby boom individual or couple will need to supplement Social Security benefits by at least $20,000 a year (in today’s dollars) for a moderately comfortable retirement. How much savings would retirees need in order to be able to spend that much each year for the rest of their lives? At age 65, retirees in the baby boom generation will have an average life expectancy approaching 20 years. Assuming an average real rate of return in the stock and bond markets of 5 percent a year above inflation, an annuity at retirement to provide $20,000 a year for life would cost about $250,000. The median saving of the typical family at retirement is less than a fifth of that amount. Savings of $50,000 would buy an annuity providing only $4,000 a year.

Even a $250,000 annuity would not provide enough additional income if either spouse required extended nursing home care or assisted living. If the family did not also have long-term care insurance (a form of saving), at least twice that amount might be needed. The alternative would be to “spend down” assets to the poverty level to become eligible for federal assistance under Medicaid. That would not provide the best care for the unwell spouse and would impoverish the other.

Sources Of National Saving

There are three categories of saving in the National Income and Product Accounts (the official measures of U.S. national production, income, and outlays published by the Department of Commerce).

Personal saving includes saving by individuals in bank accounts, mutual funds, stocks and bonds, etc., plus contributions to pensions by individuals and employers.

Business saving is revenue set aside for business investment. The Accounts break business saving into two parts, the amount saved to replace worn-out plant and equipment (called “consumption of fixed capital,” which covers a cost and is not considered part of profit) and undistributed after-tax profits kept by businesses to add to investment (also called retained earnings).

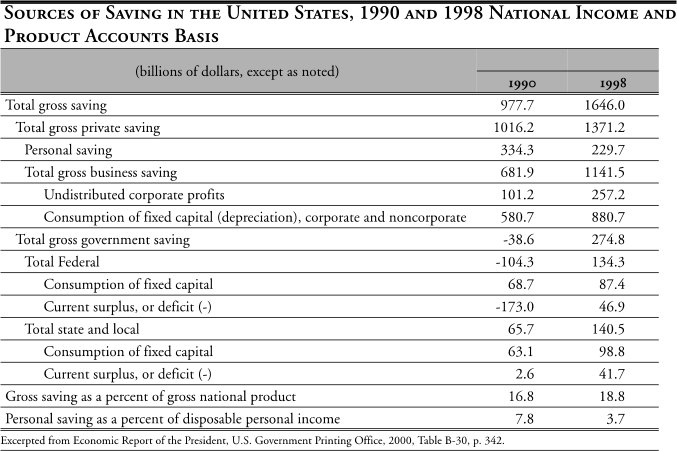

Government saving at the federal, state, and local level is similarly defined as the sum of consumption of fixed capital (spending on replacement investment) plus the government’s current surpluses or minus its current deficits. [See Table 2]

Table 2

In 1990, business saving of $682 billion was 67 percent of total private saving, while personal saving of $334 billion was 33 percent of the total, a typical ratio. More recently, personal saving has declined as a share of private saving. In 1998, business saving and personal saving were 83 percent and 17 percent of private saving, respectively. In 1990, federal, state, and local governments combined were saving at a rate of $39 billion; in 1998, they were saving $275 billion. The change was due largely to a shift of the federal government from deficit to surplus and an increase in the surpluses of state and local governments.

Although federal, state, and local government surpluses are counted as part of national saving, they should not be regarded as increasing national saving. The tax revenue that produces the government surplus comes largely at the expense of private sector saving. That is, higher government saving is offset by lower private saving. Thus, when a government official such as the former Secretary of the Treasury, Robert Rubin, says that we should not cut taxes because we need to increase national saving, he is making a mistaken assumption that the surplus adds to total national saving instead of moving it from one category to another.

How Does U.S. Saving Compare to That of the Rest of the World?

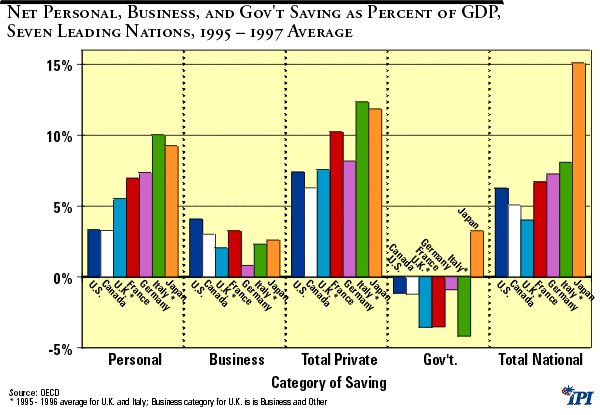

We can compare U.S. saving rates to those of other countries using data from the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD). The data show net saving (gross saving less depreciation) for many major nations as a percent of gross domestic product (GDP) for households, businesses, and governments. The household saving rate in the United States is about comparable to that of Canada but is well below that of five other major nations — averaging about 60 percent that of the U.K., about half that of Germany and France, and about a third that of Japan and Italy. [See Figure 2]

Figure 2

Business saving in the U.S is higher than in these other nations, however. Since stock ownership is more widely distributed in the U.S. than abroad, it may be that U.S. savers are letting businesses do more of their saving for them than are citizens of the other nations. Nonetheless, while on a par with that in Canada and the U.K., private saving (business plus household) in the United States as a share of GDP is only about 60 percent to 80 percent as large as in the other nations.

In recent years, U.S. government deficits have been relatively low compared to those abroad, so total U.S. net saving stacks up fairly well. It exceeds that of Canada and the U.K., is about 80 percent of that of Germany, France, and Italy, and lags only that of Japan by a wide margin. That the total net U.S. saving rate is only moderately lower than that of other major nations is not much comfort, however, because saving rates have declined in most of the developed world compared to the levels of the 1960s and 1970s.

The relatively low U.S. saving rate has not prevented the United States from having a healthy rate of investment in plant, equipment, and commercial and residential real estate in recent years. In fact, the U.S. economic growth rate has exceeded that of the other major nations, and our unemployment rate is substantially below that of our European trading partners. The reason is that the United States has been able to attract net foreign saving to finance some of the investment in U.S. capital. Each year, foreign savers and businesses buy more U.S. financial instruments, businesses, and real estate in the United States than U.S. savers and businesses buy abroad. This enables investment in the United States to exceed the amount of domestic saving. The United States and its workers clearly benefit from this net foreign investment, which boosts U.S. labor productivity and wages. The foreign savers benefit as well, receiving a rapidly increasing stream of interest, dividends, and profits.

Still, we can and should do better. Additional saving by Americans would be invested, at least in part, here in the U.S. and would boost capital formation, productivity, wages, and incomes by even more than they are already increasing. Furthermore, there are two potential disadvantages to relying on foreign saving. One is that foreign savers may not always be willing to provide us with a steady stream of additional saving, leaving us short some time in the future. This might happen if the United States were to adopt a less favorable tax treatment of investment or to allow the return of inflation. In either case, domestic saving would suffer as well. The other, more important disadvantage is that by not saving to finance more of our own investment, we deprive ourselves of the ownership of the assets and do not receive the interest, dividends, and reinvested income that the assets generate. They belong instead to the foreign savers.

What Has Been Happening to U.S. National, Business, and

Personal Saving Rates Over Time?

As mentioned, the personal saving rate (saving as a percent of “ disposable” after-tax income) has plunged over the past 15 years, from about 9 percent in the mid-1980s to nearly zero in 2000. Personal saving has also fallen as a share of GDP. Business saving has scarcely changed as a share of the economy, so total private saving has declined as a share of GDP. Over the same period, the federal budget has moved from substantial deficits to substantial surpluses, and state and local government surpluses have risen, boosting government saving as a share of GDP. The total national saving rate, the sum of these components, has recovered from a dip in the 1990–91 recession to regain its 1989 prerecession level and is about at the level of the mid-1980s. It has not, however, regained the levels of earlier decades, as when it averaged 20.3 percent of GDP between 1960 and 1982. [See Figure 3] In dollar terms, of course, the current saving rate represents a greater absolute amount or level of saving than a decade ago because today’s economy is substantially larger. Nonetheless, the low saving rate is important because it helps to determine the growth rate of income and GDP.

Figure 3

What Ails Private Saving? Blame Washington, Not Main Street

Politicians and some economists blame the public for the low national saving rate. They claim that the public is too short-sighted to save or that it is taking advantage of the rising stock market to go on a spending spree. (Imagine the government accusing the public of going on a spending spree!) But savers and businesses are not at fault. We should blame the government’s bad tax treatment of saving for the drop in the private saving rate and its improper treatment of investment for a less than optimal rate of capital formation.

Government Surpluses Versus Private Saving

Many politicians and economists fret that the decline in the private saving rate will retard “national saving” and growth. They use the decline as an excuse to hang on to large federal government surpluses projected for the next decade, rather than to cut taxes. They argue that government surpluses add to national saving and promote growth.

The truth is, government surpluses do not raise national saving and investment. The excess taxes imposed to create the current surpluses have reduced private saving and discouraged investment and growth. The government should not try to “save” for us. Instead, it should cut the tax barriers that punish private saving and investment. Total saving and investment would be higher and the country would be far better off with pro-saving and pro-investment tax cuts than with big budget surpluses.

The notion that government saving raises national saving and investment is based on the largely unjustified assumption that higher taxes primarily cut into personal consumption and leave private saving and business investment largely unchanged. If higher taxes cut into private consumption spending and left private saving unchanged, then a tax increase would raise national saving. Government deficits would be lower, or surpluses higher. Government would be borrowing less private saving, or paying down more government debt, returning the funds to private savers to lend to someone else. Either way, more of the saving done by the private sector would be available to finance private sector investment in plant, equipment, or commercial or residential buildings. This scenario has been popular with government economists and policy makers since the 1930s.

In fact, it has become clear over the years that higher taxes primarily discourage personal and business saving rather than consumption, and high taxes almost surely lower total national saving and investment. There are two main adverse effects of taxes on saving: reduced ability to save and reduced incentive to save.

Higher taxes reduce the private sector’s ability to save by depriving individuals and businesses of income that they could be saving. The first thing that individuals cut back on when their disposable (after-tax) income dips is saving, not food, clothing, shelter, tuition, or other “necessities.” When business taxes rise, business’s after-tax retained earnings are reduced.

Higher taxes reduce the incentive to save and invest out of whatever income is left after taxes. In recent decades, personal taxes have been raised through increases in personal tax rates and by curtailing eligibility for IRAs and pensions; these steps have made saving less rewarding compared to consumption. Taxes on business (corporations, proprietorships, and partnerships) have been raised by increasing corporate and individual tax rates and by reducing the value of depreciation write-offs for investment; these steps have reduced the after-tax rate of return on investment in plant and equipment and thereby discouraged corporations and small business owners from using as much capital as they otherwise would. (Business income is revenue less the cost of earning the revenue, including the cost of acquiring equipment, buildings, or inventory. Cutting the amount of these costs that investors are allowed to claim for tax purposes overstates income, raises effective tax rates, and reduces the after-tax earnings from investment.) The result is less total private sector saving and investment than would be the case if taxes and government surpluses were lower.

Misallocation, Risk, and Transaction Costs

Not only does government saving not increase national saving, it diverts saving to less than optimal uses. When an individual is left his or her own income to save, he or she may choose to lend it via the financial markets or to invest it directly in his or her education (human capital formation) or in his or her own entrepreneurial venture if these activities are likely to yield more than other investments. The individual is in the best position to judge his or her prospects. When the government taxes that income away, it recycles it through the financial markets by paying down debt or reducing federal borrowing. Individuals must then apply for a loan to get their own money back and convince the bank or the credit market, which do not have first-hand information about the borrower’s prospects, that their investment opportunities are a good use of funds. The bank will be concerned with the risk arising from its lack of knowledge of the borrower, and major transaction and paperwork costs will occur because individuals were not left their own money to save and invest in the first place. The bank may choose instead to lend to better-known but lower-yielding established businesses, or to individuals who wish to finance consumption, neither of which may be the best use of the saving.

Tax Rates Up, Saving Rates Down

Private sector saving and government saving often move in opposite directions over long periods of time as well as over short-term business cycles. Tax increases may reduce government deficits, but they tend to retard private saving by individuals and businesses.

Payroll taxes have increased substantially since 1980. The payroll tax rate rose from 12.3 percent in 1980 to 13.4 percent in 1983 to 15.3 percent in 1990. The amount of income subject to the retirement and disability portion of the tax has risen each year, from $25,900 in 1980 to $51,300 in 1990 to $80,400 in 2001. Since 1994, the hospital insurance (Medicare) portion of the tax has been imposed on all wages and salaries without limit.

The personal income tax has risen as a share of GNP since the mid-1980s, affecting workers, savers, and owners of unincorporated businesses. As real incomes have grown, people have been pushed up through the graduated tax rate structure. (Tax indexing has protected people from “bracket creep” due to inflation since 1985, but it does not protect them from paying higher tax rates as their real incomes grow.) In addition, there were explicit income tax rate increases in 1990 and 1993.

Taxes have been raised on corporations on several occasions since they were last cut in 1981, keeping corporate business saving and investment from rising as much as they might have.

All told, federal tax collections have risen from an average of 17.5 percent of GNP in the mid-1980s to just over 20 percent of GNP in 1999 and 2000. The rising tax burden has enabled the federal budget to swing from deficit to surplus. State and local government surpluses have risen slightly since the mid-1980s as a share of GNP as well. In particular, government saving is up by 6.4 percent of GNP since its trough in 1992. National gross saving rates, however, have rebounded by only 2.8 percent of GNP since 1992 because personal saving has fallen and business saving has risen only slightly relative to the economy. Compared to the mid-1980s, private saving is down and government saving is up by roughly equal shares. [See Figure 3]

Stock Market Up, Tax Rate Up, Saving Rate Down

Some economists theorize that the rapid rise in stock prices has lowered the personal saving rate and encouraged consumption because people have seen their wealth increase without having to save any current income. This phenomenon is called the “wealth effect.” This theory makes individuals out to be opportunistic spendthrifts. The assertion is twisted logic. The rise in the stock market has increased the reward to saving and has probably caused people to be more interested in saving and buying stock over time, not less. In fact, the Federal Reserve reports that the percent of families owning stock jumped from 31.6 percent in 1989 to 48.5 percent in 1998.

In other ways, however, the rising stock market may have cut the saving rate. People who traded stock at a profit or received capital gains distributions from mutual funds have had to pay substantial capital gains taxes. In order to reinvest all the proceeds of their stock sales so as not to eat into their accumulated savings, they have had to pay the capital gains tax out of current wages, interest, or dividend income. Their saving out of current income fell by roughly the amount of their higher tax payments, and their saving rate as a percent of their current ordinary (non-capital gains) income dropped. (The savers reinvested their capital gains, but capital gains are not part of current national production or income, and the rolled-over gains are not counted as part of current saving.)2

In Fiscal Year 1992, the U.S. Treasury collected nearly $29 billion in capital gains taxes. In FY 1998 (last available actual data), the Treasury collected over $82 billion in capital gains taxes, a $55 billion or 210 percent increase over six years. That $55 billion increase was equal to 20.5 percent of the personal saving done in FY 1998 (based on the recent GDP revisions and definitions). Had that extra capital gains tax money been left for taxpayers to save, and had they saved it, it would have boosted the measured saving rate that year from 4.3 percent of disposable income to 5.2 percent. If all of the $82 billion in capital gains tax taken in FY 1998 had been left for people to save (and assuming it was depressing saving to begin with), the saving rate would have been 5.6 percent. The culprit is the capital gains tax, not the savers.

Capital gains tax revenues may have grown much larger since FY 1998 because of increases in the stock market, increased capital gains distributions from mutual funds, and more frequent trading by shareholders. Government revenue estimators expect to find that nearly $118 billion in individuals’ capital gains taxes were paid in FY 2000.3 That amount, if added to personal saving, would boost the estimated FY 2000 saving rate from about 0.4 percent of disposable income to 2.1 percent.

An individual who owns stock directly can defer tax on the capital gains by holding onto the assets. Individuals who own mutual funds, however, must pay tax on any capital gains earned by the funds when the funds trade shares. The funds’ gains are attributed to the funds’ shareholders as capital gains distributions. Unless held in a tax-deferred retirement account, these distributions are taxable whether the individuals have received the gains in cash or have reinvested the proceeds. Capital gains distributions have increased dramatically, from $22 billion in 1992, $54 billion in 1995, and $184 billion in 1997, to an estimated $238 billion in 1999. The Congressional Budget Office estimates that at least 40 percent of these gains were taxable (e.g., not held in tax-deferred pension plans or IRAs).4

Also, stock market gains have boosted assets of company-sponsored defined benefit pension plans. Many companies have not had to add new money to the plans to meet their funding targets. Company contributions to workers’ pensions are counted as personal saving; the drop in current contributions has reduced the personal saving figures (dollar for dollar, since the tax deferred saving is not reduced by personal taxes). The lower pension contributions reduce business costs and raise business saving, but not dollar for dollar, because the lower labor expenses raise business taxable income and business taxes. The culprit is the tax system, not the business community.

The Wealth Effect

This is not to say that the wealth effect does not exist. Changes in wealth may indeed affect saving and consumption decisions, at least short-term, but that fact does not argue against the benefits of more favorable tax treatment of saving.

For any given level of wealth or the stock market, people will save more if the tax system is conducive to saving than if it discriminates against saving. If the tax system were neutral in its treatment of saving and consumption, the saving rate would be higher than it is at present, other things equal. A switch to neutral tax treatment of saving would probably increase the stock market and have some transitory wealth effect on the saving rate, but the permanent effect of better tax treatment of saving must be to increase the total amount of saving and capital investment, the total value of accumulated assets, and the income earned from them.

Owning a share of stock entitles a saver to a share of the company’s future income. Indeed, the price of a share of stock is the value people currently place on the future income they expect the company to earn and make available to the shareholder after corporate and personal taxes. A rise in stock prices is generally due to an increase in the expected future earnings of businesses, or to a greater degree of certainty about the earnings forecast.

In the economically unstable and inflationary period from 1968 to 1982, capital income was subjected to sharply rising tax rates, and stock prices failed to keep pace with inflation. By contrast, stock prices have risen spectacularly over the last 19 years. The increase may be due in part to rapid technological advances that bode well for future earnings. Another source of the rise has been the decline in the rate of inflation and the gradually increasing confidence that something close to price stability is likely to be sustained.

Lower inflation has reduced the effective tax rate on capital income by taking less of a bite out of the real value of the capital consumption allowances that businesses may deduct as the cost of their plant, equipment, and buildings for tax purposes. Lower inflation reduces the excess burden of tax imposed on inflated capital gains. Lower and more stable inflation also reduces risk and uncertainty, causing future earnings to be discounted at a lower discount rate, which raises the present value of any given future earnings stream and increases the price-earnings multiple of the stock market.

The drop in the inflation rate from episodes of double-digit increases in the 1975-81 period to the low single digits by the end of the 1990s has caused an increase in the market multiple (price earnings ratio). The rise in the multiple has lifted stock prices faster than the trend growth of earnings. This rise in the average price-earnings ratio has been from one level (about 10 times earnings in the 1975-81 period) to another (about 30 times earnings in 1998 and 1999). The multiple appears to have completed its adjustment to the change in the rate of inflation, and it will no longer boost the rate of growth of stock prices. The rise in stock prices in the years ahead should be more in line with the long-term trend growth rate of earnings.

An unexpected increase in one portion of one’s savings portfolio often leads to a “rebalancing”; some of the appreciated asset is sold and the holdings of other assets are increased. If a particular stock rises to become a disproportionate share of one’s holdings, some may be sold and the proceeds used to buy other stocks. A sharp rise in the stock market as a whole may encourage people to shift some assets into bonds or cash. A rise in financial wealth may encourage some people to spend more on consumer durables such as housing or cars.

Looked at another way, an increase in the stock market, and the corresponding rise in financial wealth, reflects an increase in the future income that businesses are expected to generate. As people revise the estimates of their expected lifetime earnings upward, they may increase current consumption somewhat. Of course, people cannot have their cake and eat it too. Insofar as people sell their assets and spend the increase in value, they surrender the higher future dividends and income. In view of the uncertainty surrounding such lifetime income estimates, the effect of higher wealth on consumption is apt to be fairly small. Some economists estimate that people spend only about 2 or 3 percent of an unplanned increase in their assets each year; other observers question even that effect.

There is another reason why the wealth effect on individuals may not have a major impact on the national saving rate. The wealth effect mainly impacts people who had assets prior to or who acquired them during the early stages of the market advance. People just beginning to save today must pay a higher earnings multiple (accept a lower dividend rate) to acquire a share of stock. The wealth effect is therefore a one-time effect on the behavior of a portion of the population. It should not have a permanent effect on the rate of personal saving.

We Should at Least Understand Saving before We Tax It

Seeking a Portfolio of Assets

Saving is the chief way in which we can accumulate a portfolio of assets. Saving is a flow, the direction of a portion of our current income into asset acquisition; savings is the accumulated stock of assets we have acquired over time. These assets may involve direct ownership of a small business or rental real estate, or they may be financial assets that represent a claim on the earnings of a business run by someone else. Our desire to obtain these assets in turn affects the amount of investment in physical capital (plant, equipment, buildings, and inventory) that the economy will support. There are many motives for acquiring a stock of assets: as a precaution against illness or unemployment, to be able to afford to retire, to prepare for large future outlays such as home buying or educating our children.

How much saving we do and what amount of assets we decide to accumulate and hold are influenced by the after-tax returns available on the assets, that is, the terms on which we can trade current consumption for higher future income. The more advantageous that trade, the more assets and future income we will seek to acquire. Tax changes affect the terms of the trade-off. The impact of a tax change on saving and investment does not depend on the size of the tax change in dollars, but rather on what the tax change does to the after-tax rate of return on assets and to the amount of assets we wish to own. Even a small tax change, measured in dollars, can dramatically affect the consumption-saving trade-off and the size of the portfolios that citizens want to acquire and hold. It may then take several years of additional saving or dissaving (a flow) to make the desired adjustments in the quantity of assets held (a stock). For example, reductions in the tax rates on capital gains in 1978, 1981, and 1997 have actually increased revenues in the years immediately following the rate cuts and have spurred stock ownership and saving by raising the returns to stock ownership.

Saving Is the Use of Some of Our Income to Buy Assets that Will Earn Income in the Future

When we buy a bond, we are buying a stream of future interest.

When we buy stock in a company, we are buying a share of the business and a claim to a portion of the future income of the business. The business will pay us dividends in the future or will reinvest some of our share of the profits in new ventures to make the company more valuable and increase the stock price (a capital gain).

The business uses our saving to buy physical capital (factories, machinery, or inventory) or to conduct research in order to produce manufactured products, grow crops, develop drugs, dig mines, process ore, or drill for oil, for example. All this is done on the shareholders’ behalf to earn additional income.

We may put money into a small unincorporated business, buying a machine, a building, or inventory. That direct purchase of physical capital by an individual is simultaneously saving and investment by the same person.

Saving Is a Cost of Earning Future Income

All the examples of saving listed above contained the word “buy.” Individuals have had to use some of their income to buy an asset. To do so, they have had to give up the consumption spending they could have done instead. Economists have long noted that people devote income to one use rather than another according to whether the value received from the chosen activity exceeds the value that could have been received by doing the alternative activity (the “opportunity cost”). Giving up consumption is the opportunity cost of saving, incurred at the time the saving is done.

In creating a tax system, it is important to remember that income is a net concept. Income is revenue less the cost of earning revenue. In determining how best to treat saving in designing a tax system, it is important to remember that saving is a cost of earning income.

The net income from saving is the return on saving less the principal amount saved. Consequently, income that is saved should be tax deferred (subtracted from current income) and then taxed when it is withdrawn for consumption (added to taxable income when the cost is “recovered”). Deducting the cost of saving at the time it is undertaken is called “expensing.”

Similarly, businesses should be able to deduct immediately the cost of the plant and equipment they buy, then pay tax on the returns. The deduction should take place when the investment is made, that is to say, be “ expensed,” not dragged out or amortized (depreciated) over time. Depreciation understates the cost of plant and equipment, buildings, and inventory, holding the allowable write-offs below the full present value of the outlays, and beneath the opportunity cost. This overstates business income and raises the effective tax rate.

The tax code generally does not acknowledge the cost of saving. Saving (outside of pensions and IRAs) is either not deductible, or not deducible right away. When the tax code does allow a deduction for the cost of ordinary saving, it makes us wait to account for the cost. For example, capital gains calculations allow a saver to subtract the cost of the asset from the sales price when the asset is sold. But that may be years after the saver bought the asset, when in fact the saver gave up the money (incurred the opportunity cost) at the time of purchase. The result is that income in the earlier year is overstated, raising the tax burden up front, and the income in the later year is understated. The government collects its tax sooner than otherwise, and the saver loses the opportunity to earn income on the amount taken up front in taxes. The opportunity cost of the lost earnings on the up-front taxes is part of the excess tax burden imposed on saving.

The Tax Bias against Saving and Investment — An Overview

Under the ordinary “broad-based” income tax, income is taxed when earned. If it is used for consumption, there is generally no additional federal tax (except for a few selective excise taxes) on the enjoyment of the goods and services. If the income is saved, there is another layer of tax on the earnings of the savings (the “service” being bought when the assets are acquired) — a tax on interest in the case of a bond, on dividends in the case of a stock, on the earnings of saving invested in a noncorporate business or farm, and on capital gains if new saving or reinvested business earnings cause the value of a corporate or noncorporate business to increase and the asset is sold. These are the basic income tax biases against saving relative to consumption.

Additional tax biases against saving and investment are created in two ways:

- by imposing a corporate income tax on corporate earnings in addition to taxing the shareholders’ dividends and capital gains, and

- by applying the estate and gift tax to accumulated savings.

These multiple layers of tax on saving and investment were initially advocated in the first half of the 1900s to put a heavier tax burden on upper-income Americans. At the time, only the rich had substantial savings, and, after the onset of the Great Depression, few people who were not rich had much hope of gaining great wealth. Today, with about half of American households owning stock, millions more owning assets indirectly through pension plans and insurance vehicles, and most people wanting to save for retirement, this view is no longer valid.

The tax bias against saving may have been seen as a way of putting a kinder face on capitalism and defending the free market and private property against the foreign ideologies of fascism, national socialism, and communism that seemed to be sweeping the world in the 1930s. In retrospect, however, we can see that the “broad-based” income tax retards investment, which reduces wages and employment and keeps people who lack savings and access to capital from getting ahead. It hurts the poor more than the rich.

The basic tax bias against saving can be eliminated by extending tax deferral to all saving (as we allow to a limited extent in pensions or deductible IRAs), or by giving no deduction but exempting the returns (as in a Roth IRA or a tax-exempt bond). The additional biases can be fixed by ending the double taxation of corporate income, scrapping the estate and gift tax, and allowing immediate expensing of business investment. The result would be a tax system that measured income correctly as “revenue less the cost of earning revenue” (including the cost of saving) and that imposed tax on the resulting income once and only once, at a single uniform rate, whether that income was used for current consumption, deferred for future consumption, or left to one’s heirs and beneficiaries. Adopting all these corrections would move the economy to a tax based on the amount that individuals consume each year. All the major tax reform plans — the Flat Tax, the National Sales Tax, and the USA Tax — move in different ways to an unbiased “ consumed-income” tax system.5

We Must Understand and Deal with the Basic Income Tax Bias against Saving

Where the Basic Tax Bias against Saving Comes From

Understanding this basic bias is the key to understanding all of the major tax reform proposals. The basic income tax bias against saving is due to the imposition of the tax on income that is saved and again on revenue produced by the saving. By contrast, the income tax falls on income used for consumption but does not fall again on the consumption spending and the services and enjoyment it provides. For example, if one uses after-tax income to buy a bond, the stream of interest payments is also taxed. If one uses after-tax income to buy a television, there is no additional income tax on the purchase of the TV or the stream of entertainment it provides.

All taxes raise the cost of the activities being taxed, but this biased tax treatment of saving increases the cost of saving more than it raises the cost of consumption. Any tax that raises the cost of some activities more than others is referred to as non-neutral. All non-neutral taxes distort economic activity and damage the economy. Those biased against saving and investment do the most damage.

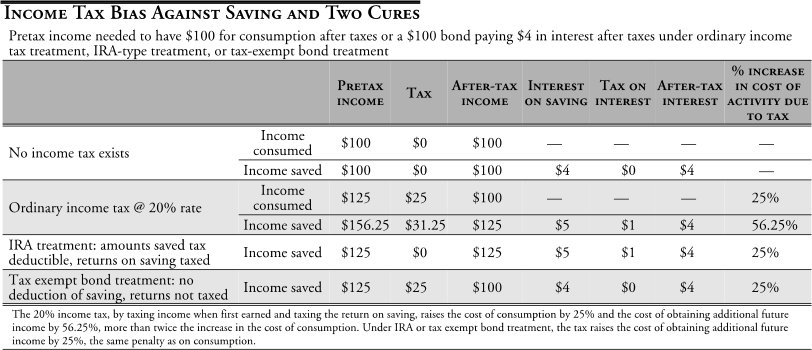

Table 3 illustrates the bias involved in imposing a tax on income that is saved and on the earnings of the saving. Suppose that, if there were no income tax, one could buy $100 of consumption goods or a $100 bond paying 4 percent interest, or $4 a year. Now impose a 20 percent income tax. One would have to earn $125, and give up $25 in tax, to have $100 of after-tax income to consume. The pretax cost of $100 of consumption has risen 25 percent. What happens to the cost of saving? To get a $4 interest stream, after taxes, one would have to earn $5 in pretax interest. But $5 in interest requires a $125 bond. To buy a $125 bond, one would have to earn $156.25 and pay $31.25 in tax. The cost of the after-tax interest stream has gone up 56.25 percent, more than twice the increase in the cost of consumption.

Table 3

Put another way, if there were no income tax, obtaining a $1 stream of interest would cost the saver $25 in current consumption ($100/$4). After the income tax, it would take $156.25 to buy a $4 interest stream or $125 of consumption. Each $1 interest stream would cost $31.25 in foregone consumption ($125/$4), 25 percent more than in the no-tax situation. This example actually understates the bias because, for simplicity, it assumes there are only two layers of federal tax on income that is saved and does not consider the third and fourth layers on corporate earning and estates.

Fixing the Basic Tax Bias against Saving

The basic tax bias against saving can be eliminated in either of two ways: by extending a tax deferral to all saving (as in a pension or deductible IRA) and taxing any withdrawals, or by giving no deduction for income that is saved but exempting the returns (as in a Roth IRA or a tax-exempt bond). The first method is called the saving-deferred approach. The second is called the returns-exempt approach. The two methods are equivalent if the taxpayer is subject to the same tax rate at the time of original saving and the time of withdrawal.

The equivalence of the two methods can be shown using the previous example. Under the returns-exempt method, interest is exempted from tax, as with state and local tax-exempt bonds. Given the 20 percent tax rate in the example, one would then have to earn $125 to buy a $100 bond, earning $4 with no further tax. Under the saving-deferred method, one is allowed a deduction for income that is saved, while the returns are taxed, as with a deductible IRA. One would have to earn $125 to buy a $125 bond, earning $5 in interest pretax, and, after paying $1 in tax on the interest, have $4 left. In both cases, the tax would increase the cost of saving by 25 percent. That is the same percentage by which the tax increases the cost of consumption. (One has to earn $125 to be able to consume $100.) Because the tax increases the costs of saving and consumption by the same percentage, it does not change their relative prices and thus does not favor one over the other. Such tax systems are called “ saving-consumption neutral.”

The equivalence of the two methods also can been shown another way. Assume a 7 percent interest rate. At 7 percent, an amount saved will double in 10 years. Under the saving-deferred method, $100 in earnings could be placed in a savings account tax-deferred. After 10 years, the account would be worth $200. If the money were withdrawn, it would be subject to our hypothetical 20 percent tax rate. After paying a $40 tax, the saver would have $160 to spend. Under the returns-exempt method, the saver would owe $20 in tax up front on the $100 of earnings. He would have $80 after taxes to put into the savings account. The account would double in ten years to $160. That sum could be withdrawn with no further tax. The after-tax amounts are the same in the two cases.

The present value of the taxes received by the government is the same in the two cases as well. In the returns-exempt case, the government receives $20 in tax before the saving goes into the account. In the saving-deferred case, the tax is recovered, with interest, ten years later. The $40 collected ten years later has the same present value as the $20 collected up front.

The saving-deferred method explicitly acknowledges the saving as a cost of earning income, and permits it to be deducted in the first year. When that “cost” is recovered in year 10, it is reintroduced to taxable income. The returns-exempt method implicitly allows for the opportunity cost of the saving by allowing the saver to keep all of the returns; the added return to the saver from not imposing tax on the interest has the same present value as the deferral would have yielded.

By contrast, ordinary income tax falls on the earnings before they are saved and then on the interest each year as it is earned. The saver can put only $80 into the account, and must give up 20 percent of the annual interest, cutting the after-tax interest rate to 5.6 percent and reducing the amount reinvested each year. At the end of ten years, the account will be worth only $138, instead of the $160 available under neutral tax treatment. The lost $22 in future value is one measure of the excess tax burden on saving.

Both methods of dealing with individual saving eliminate the excess tax on income that is saved compared to income that is used for consumption. Every major tax reform proposal employs one of these two treatments of saving and investment — the Flat Tax proposed by professors Robert Hall and Alvin Rabushka and introduced by Representative Dick Armey (R-Texas) and Senator Richard Shelby (R-Ala.), the individual side of the USA Tax (Nunn-Domenici), the Individual Investment Account proposal (McCrery-Breaux), the national retail sales tax (Shaeffer-Tauzin), or the value-added tax (the Nunn-Domenici business side).

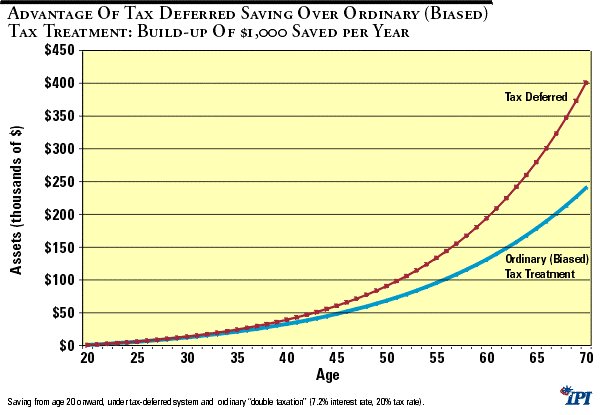

Neutral tax treatment of saving makes an enormous difference for savers. The tax bias against saving makes it harder for workers to save to buy a home, educate their children, protect themselves against medical emergencies, support their elderly parents, and build a retirement nest egg. For illustration, assume a 20 percent tax rate. Putting $1,000 of pretax income into a tax-deferred pension plan (or $800 after-tax into a Roth IRA) beginning at age 20, at a 7.2 percent real rate of return (average real growth of the stock market with dividend reinvestment since 1926), will provide $280,000 in retirement assets after federal taxes at age 65, or $400,000 at age 70. If the same $1,000 of pretax income is subject to ordinary tax treatment, only $800 in after-tax principal can be saved each year and the interest and dividends will be taxed annually. That account will provide only $178,000 for retirement spending at age 65, or $240,000 at age 70. Savers are 57 percent to 67 percent better off with tax-neutral treatment of saving. [See Figure 4]

Figure 4

The Basic Tax Bias Also Hits Direct Investment by Individuals and Corporations

Individuals who own noncorporate businesses do a portion of their saving by investing directly in plant, equipment, inventory, and buildings. Corporations invest in such assets on behalf of their shareholders. Part of the basic tax bias against saving comes from the tax code’s denying corporate and noncorporate businesses a full and immediate accounting for certain business costs in computing their taxable income (primarily, requiring depreciation instead of immediate expensing of investment), which inflates business taxable income and raises the effective tax rate.

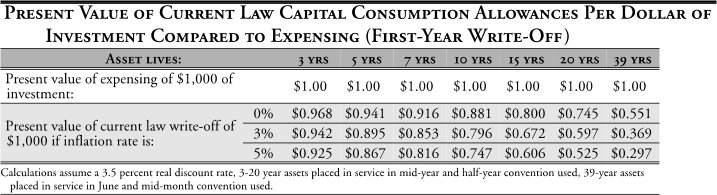

Businesses are allowed to deduct gradually the capital costs of earning additional income. The income tax allows a small amount of investment to be deducted immediately (expensed). However, the rest must be depreciated over years or even decades. Stretching out capital consumption (depreciation) allowances over an extended period reduces their value — especially for long-lived assets, which have very long stretch-out periods. Making a business wait to report some of its costs overstates and overtaxes business income.

Depreciation is effectively an interest-free loan to the government. A dollar spent on a seven-year asset gets a write-off that is worth only $0.92 in present value if inflation is zero. [See Table 5] People who erect buildings (a 39-year write-off period) get a write-off worth only $0.55 for each dollar spent. The cost of the delay becomes even greater if there is inflation. At 5 percent inflation, the seven-year asset’s write-off is worth only $0.82, and the building’s write-off drops in value to $0.30. At modest rates of inflation, the overstatement of business income by depreciation can cut the rate of return on business investment in half. This is a huge disincentive to build up capital stock. Productivity, wages, and employment suffer as a result.

Expensing is the simplest and most sensible way to provide unbiased tax treatment of direct investment in physical capital. Just as neutral treatment of saving can be accomplished by deducting saving and taxing the returns, neutral treatment of investment can be achieved by expensing investment and taxing the returns. To correctly measure business costs and income, business capital outlays for plant, equipment, buildings and other structures, land, inventory, and research and development should all be deductible in the year the outlays are made, as is the outlay for any other production input. (Alternatively, the unused portions of the depreciation write-offs should be augmented annually by a market interest rate to offset inflation and the time value of money, so that the present value of the write-offs remains equal to the full cost of the asset.) Subsequently, all the returns on these investments, including sales of goods and services, rents, and royalties (all net of other costs), and sales of assets, should be taxed.

Table 4

The Basic Tax Bias as It Affects Capital Gains

Capital gains can arise whenever a business’s prospects improve, either due to the reinvestment of previously taxed earnings, an injection of new saving that enables expansion, or an improvement in the outlook for future sales. This is true for family farms and other noncorporate businesses as well as for farm and nonfarm corporations. The development of a successful new product, or a discovery such as a new wonder drug or a new oil field, can boost the after-tax earnings outlook of a business and increase its current market value. Prospects for improved prices for agricultural products can raise the value of farmland. The current market value of a business (or its stock) is the present (discounted) value of its expected future after-tax earnings. If the higher expected future business earnings come to pass, they will be taxed in the future as corporate income and/or unincorporated business or personal income. To tax as well the increase in the business’s current value if the business or the shares are sold is to double-tax the future income of the business before it even occurs. Income tax treatment of capital gains, whatever their source, is part of the basic multiple taxation of saving.

In a neutral tax system, there would be no separate, additional taxation of capital gains. The same tax arrangements that eliminate the basic tax bias against saving can be used to avoid the tax bias against capital gains. Under the return-exempt approach, there would obviously be no tax on capital gains, because no returns on saving would be taxable. In the deductible-saving case, the cost of the assets would be expensed, that is, deducted from the tax base (resulting in no basis for tax purposes), and all the proceeds of asset sales would be properly included in taxable income. Any gain or loss embedded in the numbers would be automatically calculated correctly for tax purposes, without any special calculations required. If the proceeds of asset sales were reinvested, any embedded gains could be rolled over and would remain tax-deferred until withdrawn for consumption. These treatments of capital gains must be part of any tax system that seeks to measure income correctly so as to tax all income once and only once in a uniform manner. A bonus from either the returns-exempt or saving-deferred approach to ending the tax bias is that capital gains would cease to be a specially calculated tax item, greatly simplifying tax forms for individual and business taxpayers and reducing disputes with the IRS.

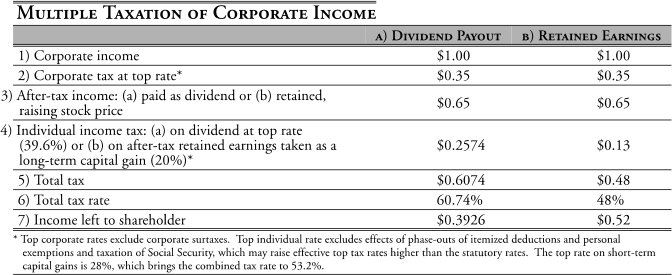

Additional Tax Bias from the Taxation of Corporations

In addition to the basic income tax bias against saving, people who save by purchasing stock in corporations face another layer of tax bias: the corporate income tax. The corporate tax takes the first bite out of corporate income. Subsequently, the shareholders must pay personal income tax on any dividends that the corporation distributes out of the after-tax corporate income. The corporate and personal layers of tax on corporate dividends are sometimes called “the double taxation of dividends.”

Note that there is a similar double tax even if the corporation does not pay dividends. If a corporation (or other business) retains its after-tax earnings for reinvestment, the earning power and the value of the business will increase. If the owner or shareholder sells the business or the shares, the increase in value is taxed as a capital gain. The corporate tax is as much a double tax on retained earnings as on dividends, except that the shareholder can postpone the tax by holding onto the shares. (Note that there are actually three layers of tax, on the original income that is saved, the corporate income tax, and then the individual income tax on dividends or capital gains from the distributed or reinvested after-tax corporate returns.)

Consequently, corporate dividends and retained earnings are both part of the double taxation of corporate income. In its latest study of corporate and individual income tax integration, the Treasury Department pointed out the advisability of dealing evenhandedly with this excess layer of corporate tax on dividends and capital gains.6 If capital gains are to be accorded a reduced tax rate, it would be wise to afford the same reduced tax rate to dividends.

A noncorporate business or farm may also increase in value if the owners reinvest some of the after-tax earnings from the business, or if they put additional saving into it out of other after-tax income. Either investment should boost future earnings and raise the present value of the business. The resulting increase in value may trigger a capital gain, taxation of which would be part of the basic double taxation of income that is saved.

Eliminating the additional layer of tax on corporate income would require taxing corporate income either on the corporation’s tax return or on the shareholder’s tax return, but not both. In the first case, shareholders would not pay tax on any dividends received, nor on any capital gains when they sold stock. In the second instance, the corporate income tax would be eliminated. The corporation would report its total income, not just its dividend payouts, to its shareholders to be taxed on their returns.

The combined corporate and personal income taxes on dividends exceed 60 percent for some savers, leaving the highest-taxed shareholders less than $0.40 in after-tax return on each dollar of corporate earnings paid as dividends. The tax rate on retained earnings resulting in a long-term capital gain reaches 48 percent. [See Table 5]

Table 5

Another layer of tax arises if one corporation owns shares in another. Corporations are taxed on the capital gains they receive if they sell shares in another company and on a portion of any dividends they receive from nonsubsidiaries.7 Shareholders of the receiving corporation then face additional tax as the dividends are passed on to them and on the gains when they sell their shares in the receiving company.

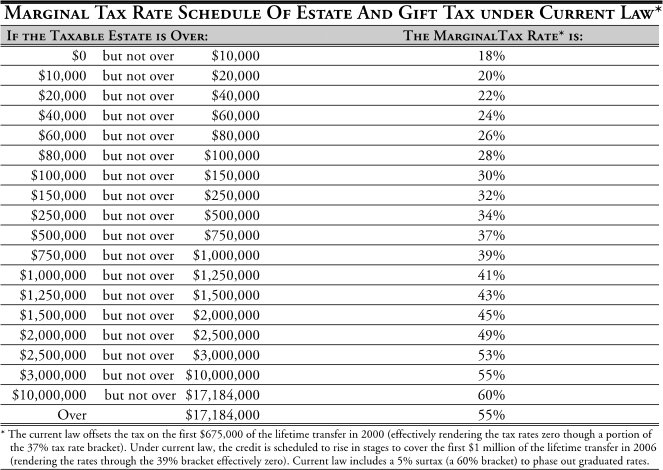

Additional Tax Bias from the Estate and Gift Tax

The federal government imposes a unified estate and gift tax (the “death tax”) on the cumulative transfers made during a person’s lifetime and at death to persons other than spouses. The tax should be eliminated. Every cent saved to create an estate has either been taxed or will be taxed under some provision of the income tax. Ordinary saving by the decedent was taxed repeatedly when the decedent and the companies she or he may have owned shares in paid individual and corporate income taxes. Saving by the decedent in a tax-deferred retirement plan will be subject to the heirs’ income taxes and was subject to the corporate income tax in the case of stock holdings. The death tax is always an extra layer of tax. As this is being written, Congress is considering reducing the estate and gift tax in the 2001 tax bill. 8

Under current (pre 2001) law, a single graduated rate schedule is applied to cumulative lifetime taxable transfers. The bottom rate is 18 percent on the first $10,000 of taxable transfers, rising to a 55 percent rate on transfers over $3 million. A 5 percent surtax is imposed at death on taxable transfers between $10 million and about $17 million; the surtax boosts the marginal tax rate to 60 percent on transfers in that range and phases out the benefits of the graduated rates. On transfers above that, the tax rate is a flat 55 percent on the entire taxable estate. [See Table 6]

Table 6

As of 2000 and 2001, a unified credit exempts the first $675,000 of transfers from tax, effectively eliminating the brackets below 37 percent. The exempt amount will rise to $700,000 in 2002 and 2003, $850,000 in 2004, $950,000 in 2005, and $1 million in 2006 and thereafter; it will not be adjusted for inflation.

An additional write-off of up to $675,000 is allowed for family businesses. The sum of this allowance and the unified credit may not exceed $1.3 million, and the heir or a member of the heir’s family must materially participate in the business for five years of any eight-year period within 10 years following the decedent’s death.

As of 1998, individuals could give $10,000 a year to any number of recipients tax free. The annual exempt amount was indexed for inflation beginning in 1999.

A graduated credit of up to 16 percent of an estate is allowed against state death taxes. So long as state death taxes are less than the federal credit, the maximum combined tax rate is the statutory federal rate.

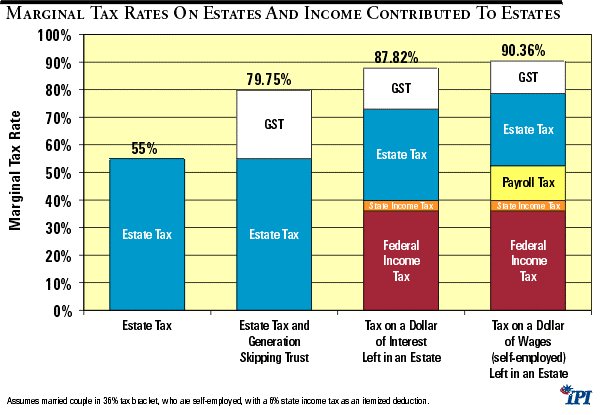

A generation-skipping transfer tax (GST) is imposed on either trusts or direct transfers to individuals more than one generation below the transferor (e.g., from grandmother to granddaughter). An exempt amount of $1 million was indexed beginning in 1999. The rate is the top estate tax rate of 55 percent on transfers in excess of the exemption. The 45 percent of the transfer remaining after the GST is also subject to the estate tax. In effect, under certain circumstances, the government takes 55 percent of the transfer or trust, and another 55 percent of the remaining 45 percent, as if the assets had been taxed passing from grandmother to daughter and then from daughter to granddaughter. The combined tax rate can reach nearly 80 percent. [See Figure 5]

If a couple nearing retirement is thinking of continuing to save or to work merely to add to their estate, they should think again. Additional interest left in an estate is subject to federal and state income taxes as well as a future estate tax, with combined rates of 73 percent to 88 percent. Working to add to an estate is also subject to the payroll tax, driving combined tax rates to 88 percent to 90 percent.

The basis of inherited assets is “stepped up” (or down) to fair market value as of the date of death. (Alternative dates of six months after death or the date the property is sold or distributed by the estate may be selected.) In effect, any capital gains or losses accrued while the decedent was alive are excluded from tax considerations. The basis of an asset acquired by gift is not “stepped up”; it is generally the same basis as the donor’s (or fair market value, whichever is less).

Figure 5

Inherited tax-deferred saving plans such as 401(k), 403(b), Keogh plans, SEPs, and regular IRAs must be taken into taxable income by heirs other than spouses over specified time periods, subjecting the assets to the income tax. Heirs are required to begin (nontaxable) withdrawals from Roth IRAs within specified time periods so that the subsequent earnings on the savings do not continue to accumulate tax free. (The contributions to the Roth IRA were taxed at the time they were made.) In both cases, current law ends the neutral tax treatment accorded the plans during the decedent’s lifetime.

Entertainer Oprah Winfrey pegged the nature of the estate tax clearly and accurately when she complained that it is a very high-rate tax which retaxes funds that were already taxed . “I think it’s so irritating that once I die, 55 percent of my money goes to the United States government....You know why that’s so irritating? Because you have already paid nearly 50 percent [when the money was earned].”9

How Should Estates Be Treated?

Under a saving-deferred income tax, inherited assets received would be treated like any other saving. The decedent would have deferred tax on his saving when he bought the assets. If the heir were to sell them and spend the money, the proceeds would be taxable. If the heir were to leave the assets in saving, they would remain tax-deferred until such time as they were sold for consumption. Assets transferred during life would also remain tax-deferred until the recipient sold them for consumption. IRAs and pensions are treated in this manner under current law in the case of a surviving spouse, who can roll the assets over into his or her retirement plan. Other heirs, however, are forced by law to take the inherited IRA or pension assets out of their tax-deferred status and to pay tax on any previously deferred income over a period of time.

Under a returns-exempt system, all saving would be on an after-tax basis, including the assets in an estate. Since the saving that built the assets was taxed when first earned, there would be no additional estate tax. Assets transferred during life would also be on an after-tax basis.

Fixing Marginal Tax Rates As Well As the Tax Base

As if the multiple layers of tax on saving were not bad enough, the damage is increased by peculiar features of the tax code that effectively increase the marginal statutory tax rates applied to income. The tax rates that matter for economic decisions are the marginal tax rates, the tax that would be imposed on the next unit of activity. Marginal tax rates govern the choice between working longer or taking more leisure and between consuming more or saving more.

The current personal income tax has five statutory marginal tax rates: 15, 28, 31, 36, and 39.6 percent.10 An “alternative minimum tax” with rates of 26 percent to 28 percent applies on a broader definition of taxable income. These graduated tax rates act as escalating excise taxes that ultimately choke off effort. The higher one’s productivity and income, the more the tax rate discourages effort.

However, the statutory marginal tax rates don’t tell the whole story. Tax rates can be much higher than they appear. If the tax system hits the same income more than once, or if tax rules overstate actual income, then the effective tax rate may be much higher than the apparent statutory tax rate. Consequently, it is not enough to have low tax rates. We must also have the right tax base. Correcting the tax base is at the heart of all of the major tax reform proposals.

Phase-ins and phase-outs in the tax code produce hidden rate hikes. In some cases, earning an extra dollar of income causes taxable income to go up by more than $1 because a tax credit or exemption is phased out or a tax is triggered on Social Security benefits. And sometimes the tax rules overstate a taxpayer’s actual income to inflate Treasury revenue. All these cases result in a higher effective marginal tax rate. Phase-outs and phase-ins should be eliminated or replaced with a less destructive method of including the income in the tax base.

The tax code includes at least two dozen phase-outs and phase-ins, and more are added with each new piece of tax legislation. The complexity is astonishing and frustrating to taxpayers.11

Upper-income taxpayers must phase out their personal exemptions and part of their itemized deductions as their income exceeds certain thresholds.12 The phase-out raises the top tax rates by about 2.5 to 5 percentage points for a couple, depending on their number of dependents. The top marginal income tax rate is effectively pushed into the low 40s.

Almost all the personally managed retirement and education saving incentives and child credits in the tax code are phased out as incomes increase.

Even the poor face high marginal tax rates. Working parents with between $19,000 and $30,000 in income face an extra 16 or 21 percent implicit tax rate as they earn additional money, because their Earned Income Tax Credit is phased out by 16 or 21 cents for each additional dollar they earn, depending on whether they have 1 or more children. They also face a 15 percent income tax rate and a 15.3 percent payroll tax rate on an extra dollar of wages, plus state income taxes. Their combined tax penalty on added income is close to or above 50 percent.13

High Tax Rates on Saving Due to Taxation of Social Security Benefits

Social Security recipients face particularly high marginal tax rates. Social Security benefits are phased into taxable income at a rate of $0.50 or $0.85 for each dollar by which the sum of the recipients’ interest, dividends, and pension income plus half of their Social Security benefits exceeds certain thresholds. The extra jump in taxable income effectively raises tax rates on those sources of income. For beneficiaries normally in the 28 percent tax bracket, marginal tax rates on income from savings can reach 42 percent or 52 percent. The taxation of benefits plus the payroll tax can boost the implicit marginal tax rates on wage income in excess of the thresholds to roughly 55 to 65 percent. For wage income that is also subject to the Social Security earnings test, the combined federal income tax rates and loss of benefits can cost retirees 109 percent of their added income, even before state income taxes. These terrible tax rates could be avoided if some benefits were exempted from tax to protect people with low incomes and the rest were simply added to taxable income without reference to other income received by the taxpayer.

The so-called tax on Social Security retirement and disability benefits is really a tax on other, private income — interest, dividends, pensions, and wages — received by individuals collecting Social Security benefits. The taxation of benefits is triggered as other retirement income exceeds a set of thresholds, not by any change in one’s Social Security benefits, which are set by a formula beyond an individual’s control. Consequently, it is the other retirement income that bears the additional tax, not the benefits. The result is a tax on other income at super-statutory rates, resulting in a sharp disincentive for private retirement saving or continued work. The tax poisoning of private retirement saving sends a terrible message to savers of all ages: “Congress does not want you to save for retirement.” The super-normal tax rates on wages sends a terrible message to older workers: “We don’t want your brains, skills, or experience in the work force.”

Under current law, benefits start to be taxed when modified adjusted gross income (MAGI) — the sum of a beneficiary’s ordinary adjusted gross income (wages, interest, pensions, dividends, etc.), tax-exempt bond income, and half of Social Security benefits — exceeds $32,000 for a married couple filing jointly and $25,000 for a single taxpayer. For each dollar by which MAGI exceeds the exempt amounts, $0.50 of the taxpayer’s Social Security benefits becomes taxable income, up to half of benefits.

As benefits become taxable, earning another dollar of taxable interest, dividends, pensions, or wages increases taxable income by $1.50, effectively raising the marginal tax rate on the added dollar of income to 1.5 times the statutory rate, e.g., from 15 percent to 22.5 percent or from 28 percent to 42 percent. An added dollar of otherwise tax exempt interest raises taxable income by $0.50, subjecting the otherwise untaxed interest to de facto marginal tax rates of 7.5 percent for taxpayers in the 15 percent bracket and 14 percent for taxpayers in the 28 percent bracket. Once half of benefits have become taxable, additional earnings again face normal marginal tax rates. (The 31 percent and higher tax rates are not affected. Half of benefits become taxable before a taxpayer’s income exceeds the 28 percent tax bracket.)

In 1993, Congress increased the amount of Social Security retirement and disability benefits subject to income tax to 85 percent for married couples with MAGI above $44,000 and for single beneficiaries with income above $34,000. Affected beneficiaries have to add $0.85 of benefits to taxable income for each dollar of MAGI over these thresholds until 85 percent of benefits become taxable. This increases the marginal tax rate spike to 1.85 times normal rates. The 15 percent marginal income tax rate becomes 27.8 percent, and the 28 percent marginal income tax rate jumps to 51.8 percent.

Congress should do more than repeal the 1993 increase in the amount of Social Security benefits subject to tax. Congress should remove both the 50 percent and 85 percent phase-ins by decoupling the taxation of Social Security benefits from the amount of a taxpayer’s other income. That is the only way to eliminate the resulting spike in marginal tax rates on interest, dividends, pensions, wages, and other privately provided retirement income.

For example, benefits above some exempt amounts, up to half of total benefits, would simply be added to ordinary taxable income. The exempt amounts, say, $6,000 for a single retiree, $9,000 for a couple using the 50 percent spousal benefit, and up to $12,000 for a two-worker couple each receiving his or her own benefits, could be adjusted to produce the same, higher, or lower revenue than current law, as desired. (Including no more than half of total benefits is suggested because it will roughly correspond to the half of the payroll tax paid by the employee, for which no income tax deduction was allowed, and which was, therefore, already taxed.)

Of course, Social Security affects national saving in another way. The payroll tax hits wage income a second time, adding 15.3 percent to the tax rate on labor compensation. The resulting reduction in work and hiring incentives reduces employment. With less labor to work with, capital is less productive, which discourages saving and investment. The payroll tax also reduces the ability to save by cutting income, and the promise of Social Security benefits, if believed, reduces the perceived need to save. The cure is to privatize retirement saving, eliminate the payroll tax, and allow individuals to put the money into their own personal retirement plans.

Why the Tax Treatment of Saving and Investment Matters, and Why We Need Reform

These tax biases are real and so are their consequences. They have discouraged several trillion dollars in saving and investment, considerably retarding the growth of productivity, wages, and employment, and slowing the growth of individual income and wealth. It is no exaggeration to suggest that the level of income in the United States could be at least 10 to 15 percent higher than it is today if these biases did not exist. The missing income has simply been thrown away to no good purpose. The current system also cripples people’s ability and incentive to save for retirement, leaving people with less retirement income than they need to be financially secure and increasing their dependence on government programs or their children in old age.

The tax bias against investment restricts the amount of capital formation in the United States, which depresses productivity, wages, and employment. Some tax proposals would improve the tax treatment of personal saving but would do nothing to encourage businesses to use the saving to expand their operations in the United States. In that event, the added saving might go into foreign securities or global mutual funds, substitute for some foreign money flowing into U.S. financial markets, or be borrowed by businesses to expand operations abroad. If we want U.S. workers as well as savers to benefit from tax reform, we need to encourage domestic investment as well as saving.

Fundamental Reform

All the major fundamental tax reform proposals eliminate the multiple taxation of saving and investment inherent in the broad-based income tax, and all provide a neutral tax system. The national sales tax and the individual portion of the USA Tax (Nunn-Domenici) are, in effect, saving-deferred taxes. The Armey Flat Tax is a returns-exempt tax for individuals, and a saving/investment-deferred tax for businesses. A simple, single rate saving-deferred cash flow tax for individuals would be another possibility, and the clearest way to show taxpayers what they are paying for government. 14

One way or another, we need to reform this inequitable, inefficient, and unproductive tax system. A single rate tax, unbiased against saving, with no double taxation of business income and no tax on estates, could eliminate these hidden, high marginal tax rates. Moving to neutral tax treatment of saving and investment could add 25 to 30 percent to the stock of capital, boost productivity and wages, and raise national income by 10 to 15 percent over about 15 years. That would boost the average family income by $4,000 to $6,000 a year during their working lives. It also would guarantee a far more secure retirement for future generations by encouraging additional asset accumulation. Fundamental tax reform would work hand-in-glove with the privatization of Social Security to benefit people during their working and their retirement years. In short, fundamental tax reform would reward people for improving their situations and would expand economic and political freedom for the new millennium.

Endnotes

1 http://www.ssa.gov/OACT/TR/TR01/lr3B5-a.html

2 The price of an asset is the value that people put on the future income the asset will generate after taxes. The current price of the asset will rise if there is an increase in the asset’s expected future after-tax income, and there will be a capital gain if the asset is sold. The asset’s higher future income will be counted — and taxed — as part of national income in future years, when it is earned. Counting the rise in the asset’ s current value in this year’s national income would be double-counting that future income. Similarly, including capital gains in taxable income is double-counting and double taxation; that is why the correct tax rate for capital gains is zero

3 The Budget and Economic Outlook: Fiscal Years 2002-2011 , (Congressional Budget Office, January 2001, Table 3-6, p. 60.)

4 “The Contribution of Mutual Funds to Taxable Capital Gains,” Congressional Budget Office, October 1999.

5 For a description of a simple saving/consumption neutral tax system, see “ The Inflow-Outflow Tax,” available from the Institute for Research on the Economics of Taxation (IRET), www.iret.org.

6 Department of the Treasury, Integration of the Individual and Corporate Income Tax Systems, Taxing Business Income Once , Washington, D.C., Jan. 6, 1992. In the introduction, p. 13, the study states: “Integration should distort as little as possible the choice between retaining and distributing earnings. The U.S. corporate system discourages the payment of dividends and encourages corporations to retain earnings...” Also see the section entitled “Bias against Corporate Dividends Distributions,” pp. 116–18.

7 Suppose Corporation B owns shares in Corporation A. When Corporation A earns money, it pays tax. Then Corporation B, the recipient, pays tax when it receives a dividend from A or sells its shares in A. Corporation B obtains some relief if it is paid in dividends: the dividends-received deduction excludes from tax 70 percent of inter-corporate dividends. (The exclusion becomes 80 percent if B owns at least 80 percent of A and 100 percent if the companies are affiliated.) Corporation B obtains no relief, though, if it is paid via capital gains; it is then taxed at the full corporate tax rate, which is 35 percent for large companies. To lessen the multiple taxation of income at the corporate level, the corporate capital gains tax rate should be reduced and/or corporate capital gains realized when one company sells shares in another should qualify for an exclusion analogous to the dividends-received deduction. Also, the dividends-received deduction should be increased.