When the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) came into effect, the U.S. economy was already more dependent on innovation than upon traditional manufacturing. That’s one reason why NAFTA was the first free trade agreement to include protections for intellectual property (IP). And in the 25 years since, that trend has only continued. Today, the U.S. is a creators’ economy; we patent new inventions, copyright new creative works, and trademark strong new brands.

These industries, identified as the “IP-intensive” industries by the Commerce Department, are responsible for nearly one-third of all U.S. jobs and for more than 38.2 percent of U.S. gross domestic product. So there’s a good chance you or someone close to you works in these industries such as software, music and book publishing, movies and entertainment, pharmaceuticals, chemicals and enzymes, patented and hybridized plants and seeds, microchip design or aircraft manufacturing.

Today, in what appears to be the end-stage of NAFTA renegotiation, it is critical that any revision of NAFTA includes strong, updated protections for IP goods and services. While NAFTA has been a better deal for the U.S. than President Donald Trump has claimed, revisiting NAFTA provides an opportunity to materially improve the agreement for all parties involved, including updating its IP protections.

If a new NAFTA doesn’t improve IP protections, it’s not a better deal.

IP Goods Dominate U.S. Exports

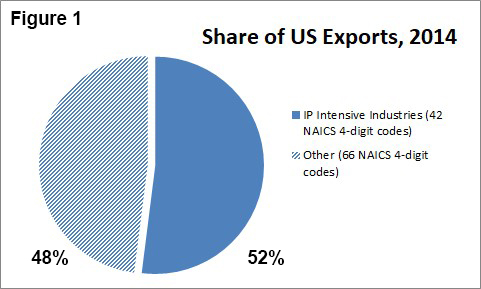

An examination of the data demonstrates that the IP industries are the largest category of U.S. exports.

The Department of Commerce has identified what it calls the IP-intensive industries. Using the North American Industry Classification System (NAICS), the Commerce Department determined that 42 of the high level (4 digit) NAICS codes comprise the IP-intensive industries, leaving 66 non-IP-intensive industry categories. Using the most recent data (2014), Figure 1 shows that, when U.S. exports are allocated according to these two divisions, 52 percent of U.S. exports are from the IP-intensive industries. Over the past decade, the IP-intensive industries have always represented greater than 50 percent of U.S. exports, and in 2010 represented fully 60 percent of U.S. exports.

In other words, IP goods and services dominate U.S. exports. Not to put too fine a point on it, but trade discussions have tended to prioritize agriculture and heavy manufacturing, and have treated the IP industries as an afterthought. But in view of the fact that IP goods and services comprise the majority of U.S. exports, to not prioritize IP protections in trade agreements is trade malpractice.

This dominance of IP goods over other categories of U.S. exports underscores the fact that the world buys from the United States the products of our innovation and creativity—and those products tend to be protected by some form of intellectual property. Creativity and innovation is the American competitive advantage.

The U.S. Economy Depends on IP

The contribution of the IP industries to the overall U.S. economy is significant. According to a 2016 Department of Commerce study using 2014 data, the IP-intensive industries:1

- Directly account for 27.9 million jobs, or 18.2 percent of all employment;

- Indirectly support 17.6 million additional jobs, totaling 45.5 million jobs or 30 percent of total employment;

- Account for $6.6 trillion in value added, or 38.2 percent of U.S. GDP; and

- Account for 52 percent of total U.S. exports.

It is clearly in U.S. interests to include strong IP protections in trade agreements. Indeed, for the U.S., IP protection is central to trade.

Specific IP Issues in NAFTA 2.0

There are several key areas where NAFTA 2.0 must enhance or update IP protections.

First, while Mexico is a signatory to the WIPO Internet Treaties, which set international norms for the protection of copyright, Mexico has yet to implement the treaties through domestic legislation. The U.S. should insist that Mexico implement the WIPO Internet Treaties and adopt other basic protections for copyright, such as making camcording in movie theaters illegal.

In other copyright areas, while no one is completely happy with the attempt to balance interests in the notice and takedown system for online infringement in the U.S., any country with a free-trade agreement with the United States should be required to implement or improve protections against online infringement, which inevitably ends up involving limited safe harbors on the front end but also statutory damages for infringement.

Efforts to write specific fair use exceptions and limitation into NAFTA 2.0 should be resisted. Whatever fair use exceptions are appropriate for a particular country should be determined by domestic law, not international treaty. The international IP system purposely contains sufficient flexibilities for countries to adopt whatever fair use exceptions are appropriate.

On patents, Canada has been purposely undermining the patents of U.S. companies as a matter of national strategy. NAFTA 2.0 is an excellent opportunity to insist that our trading partners respect and appropriately value the products of American innovation.

In the pharmaceutical area, while cutting-edge biologic drugs have 12 years of data protection in the U.S., Canada only allows eight years of data protection, and Mexico hardly protects biologics at all. NAFTA 2.0 should insist on 12 years of data protection for biologics, consistent with U.S. law.

Further, almost all of our trading partners around the world have price controls on prescription drugs, which means those countries don’t bear an appropriate share of funding pharmaceutical innovation. That leaves Americans stuck with the bill. The only way to reduce the cost of drugs to Americans without stifling innovation is to reduce our trading partners’ free-riding on American innovation. NAFTA 2.0 should include provisions designed to encourage both Mexico and Canada to bear more of the cost of the pharmaceutical innovation that they enjoy, and should demand government pricing decisions be determined through a transparent process.

A new NAFTA should also insist on stronger protections against IP theft and against policies that discourage trade in digital goods and data. NAFTA signatory countries should be prohibited from enacting data localization requirements, customs duties on data transmissions, and from requiring companies to surrender proprietary information like encryption keys, software code, etc.

Conclusion

The U.S. economy is increasingly dependent on the products of innovation, creativity and invention, and so policies that support innovation and creativity should be priorities for the U.S. government, especially in trade agreements.

President Trump is not wrong that NAFTA can and should be improved, and that those improvements would benefit U.S. workers and consumers. But U.S. negotiators must insist on stronger IP protections, or what is likely to happen is some tweaks around the edges of NAFTA without dramatic improvements in the IP chapter. Such a new NAFTA will be a missed opportunity and a failure to deliver on a key campaign promise.

Endnote

1. Department of Commerce, “Intellectual Property and the U.S. Economy: Industries in Focus” (April 2016, based on 2014 data).