- Lawmakers from both parties are decrying energy companies’ “price gouging” of gasoline and have suggested price controls might make gas more affordable.

- The Washington, DC, city council has passed price-control legislation on pharmaceutical manufacturers; the price of brand name drugs sold in the district can’t be more than 30 percent higher than those drugs are selling in Europe.

And there are more examples. So maybe it’s time to refresh legislators’ memories about what has been well understood by most economists for years: price controls don’t work.

A Price Is Information. The most important thing to understand about a price is that it is a powerful conveyor of information, both from the seller to the buyer, and from the buyer to the seller.

If buyers are resistant to a price, vendors have to lower it to a point where consumers are willing to pay. If there isn’t such a price point, the vendor will have to change its business plan or fail.

For example, both Ford and GM have to significantly discount many of their vehicles to attract buyers. Indeed, the “list price” on most brands has been ignored for years.

With some products and services, however, consumers may be willing to pay significantly more than the list price for highly desirable or limited-availability goods, such as Microsoft’s new Xbox 360.

When government attempts to manipulate prices through price controls, it distorts the flow of information. The controlled price is what politicians or bureaucrats, not consumers, think it should be.

Price Controls Undermine Competition. Price controls are supposed to keep high prices from hurting working families, which presumably cannot afford a sharp increase in the price of certain essential goods and services.

But it is well known that price controls don’t always keep prices low. Sometimes they keep prices artificially high. For example, Congress routinely imposes price supports on milk and sugar, which deprive consumers of the benefit of lower-priced products. Almost everyone knows that if the price controls were removed from milk and sugar, competition would expand and prices would fall, making the products more affordable for everyone, but especially the poor.

That lack of competition—restraint of trade, actually—results in higher prices for everyone.

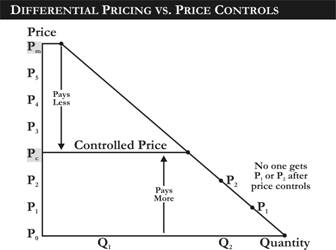

Price Controls Hurt the Poor. To understand why price controls hurt the poor, examine the price curve in the figure below.

Sellers set a price for their products or services that they believe will maximize revenue ( Pm ). That price may be higher than many people can or are willing to pay. However, sellers are also aware that by finding ways to discount their products or services, they can gain even more revenue. But the discounting—also referred to as “differential pricing”—has to be done in a way that doesn’t cut into their normal market.

For example, movie theaters have a set price for a movie if seen in the evening, the peak time for moviegoers. But they may provide small discounts for seniors and students, groups that are easy to identify and typically have less discretionary income. More importantly, the theater may provide a blanket discount to everyone who attends before a certain time (i.e., the matinee price). Those who aren’t willing or able to pay the full price now have an option, if they are flexible and can accommodate the earlier showing.

Retailers also engage in differential pricing. At the beginning of a season, new designer garments are marked at full retail price. Later in the season, or after holidays such as Christmas, retailers will discount items 25 percent, then 50 percent and maybe eventually 75 percent. At some point, the price is low enough that almost anyone can afford high-end clothing—if they are willing to wait.

Thus products and services actually move up and down a demand curve (P0 -P 5 ), and seldom hold at one set price.

When politicians decide to impose price controls (Pc ), they usually pick a level that is lower than the top price (Pm ) the seller would like to sell at, but higher than the lowest price (P 0 ) the seller may be willing to sell at under certain conditions. [Again, see the figure.]

As a result of government price controls, highly motivated consumers who were willing and able to pay the full price actually get a lower price, while less-motivated or less-able consumers must pay a higher price than they would otherwise have had to pay if prices were free to move.

Drug manufacturers set a price for their products, but they also engage in differential pricing. The companies and their trade associations have established nationwide programs that provide drugs for little or nothing to low-income people. They also deeply discount or give away their products to very poor countries. When the government sets the price—say, by telling drug manufacturers they cannot charge more than some percentage of what they charge in another country, or that a company must sell to every purchaser at the lowest price paid by any purchaser (a provision that passed the Senate a few years ago)—it is almost always above what the poorest had been paying for the drug. Drug manufacturers set a price for their products, but they also engage in differential pricing. The companies and their trade associations have established nationwide programs that provide drugs for little or nothing to low-income people. They also deeply discount or give away their products to very poor countries. When the government sets the price—say, by telling drug manufacturers they cannot charge more than some percentage of what they charge in another country, or that a company must sell to every purchaser at the lowest price paid by any purchaser (a provision that passed the Senate a few years ago)—it is almost always above what the poorest had been paying for the drug.

Price Controls Distort Markets. Because markets must have the free flow of price information, and because price controls distort that information, price controls distort markets.

Take Medicare, for example. In 1983 Congress passed legislation that imposed price controls on how much Medicare reimburses hospitals for services rendered. As a result, hospitals started charging private sector health insurers more (i.e., cost shifting) to offset their losses from Medicare price controls. HMOs then entered the picture by negotiating huge discounts off of the inflated private sector prices. Today, consumers pay widely divergent prices for hospital services based solely on their particular insurance situation. It is a dysfunctional market, and the primary reason is Medicare price controls.

Price Controls Undermine Accountability. In a normal market, consumers determine prices by their willingness to pay; when the government controls the price, the consumer becomes irrelevant. That’s because the government becomes the customer, and prices are then determined by which company or industry has the best lobbyists, not which ones provide the best value for the consumer’s dollar.

Price Controls Destroy Innovation. For decades states created and supported a monopoly in the landline telephone system, and controlled the prices telecom companies charged consumers. Consumers could only choose from one vendor, were told what they had to pay, and could have any color telephone they wanted—as long as it was black. With no competition, but especially with no pricing flexibility, little innovation made its way to the consumer. Phone companies were in the business of negotiating rates from government entities, not the innovation business.

By contrast, wireless phone companies were not subject to price controls and certain other regulations. The result was an explosion in consumer choice, immediate access anywhere, and an array of new types of phones. In this largely non-price-controlled arena, more innovation and lower prices are commonplace. Today, the lessons learned from the wireless industry are finally resulting in more pricing flexibility for the landline phone business.

Conclusion. We have been down the price control path so many times with so many products and services that you’d think the politicians would have come to realize that price controls—whether direct or indirect—stifle competition, keep prices artificially high and destroy innovation. It’s time the politicians learn that lesson for good.