One of President George W. Bush’s most important and controversial campaign proposals was to let workers place a portion of their Social Security payroll tax into Personal Retirement Accounts (PRAs). That seemed to many people like a great idea when the stock market was reaching new heights. But recent market volatility—the market having lost, by some estimates, about $4 trillion in value1 —has forced the public, the media and members of Congress to reconsider the wisdom of allowing workers to invest their Social Security retirement funds in the stock market.

Nevertheless, American workers want and need to make more than the roughly 2 percent or less interest they earn from their Social Security payroll tax contributions.2 And many are aware that Social Security is facing a financial day of reckoning—around the year 2016, according to the 2001 Social Security trustees report.3 The Social Security trust fund may be in good financial shape today—but it won’t be for long.

But how are we to create a Personal Retirement Account option that will ensure a better return on workers’ savings—thereby providing a better and more financially secure retirement—while insulating account-holders from the risk often associated with the stock market? The answer is to shift our thinking about Personal Retirement Accounts from an “IRA model” to a “banking model,” or, to put it another way, from an “investing model” to a “savings model”—what will henceforth be referred to as a Retirement Savings Account (RSA). Can such a model work? It already does. In fact, thousands of Americans have had Retirement Savings Accounts based on a banking model for 20 years—and they have never lost a dime.

The Need for Social Security Reform

A recent law passed by Congress requires the Social Security Administration to mail to most Americans a statement indicating their taxed Social Security earnings over the years and how much they can expect to receive at retirement at their “current earnings rate.”4 However, the letter may be misleading in that it conveys the impression that there is a pool of money set aside for each worker’s retirement. Unfortunately, that’s just not the case.

A Pay-As-You-Go System

Social Security is based on a pay-as-you-go system. Payroll taxes paid by workers today are sent out to cover current retirees’ benefits. According to the Social Security trustees’ “intermediate assumptions,” both the Old Age Survivors Insurance (OASI) and the Disability Insurance (DI) programs will maintain a surplus until the year 2016.5 That means workers will be paying in more than is paid out to current retirees for approximately 15 more years. After 2016, however, the federal government will have to make up the deficit between trust-fund income and payout. While it is true that the trust fund also holds IOUs from the federal government, which borrowed—and spent—past trust fund surpluses, the only way the federal government can repay those IOUs after the surplus is gone is by borrowing the money, printing it, raising taxes and/or redirecting dollars from other parts of the budget. Thus, those who argue that the trust fund is solvent until 2038—the year the trustees say the IOUs for the OASDI programs officially run out—are being disingenuous. The federal government has no real assets to pay those IOUs when the trust fund starts needing money in 2016.

Demographic Realities

When the Social Security program was created in 1935, it was based on certain demographic facts that are no longer true.

• People lived shorter life spans, with the average life expectancy in 1940 being only 64 years; and there were only 9 million people over the age of 65.6

• The rate of population growth, and therefore the numberof workers, was rising, reaching 3.7 children per couple in 1957.

• The ratio of workers to retirees was high, about 42 to 1;

• And, thus the payroll tax was low—1 percent each from the employer and employee up to $3,000 in income, for a maximum of $60 per year per employee.

Today, things are very different. By 1999 there were 31 million retired workers and dependents drawing on Social Security, along with 6.5 million disabled workers and 7 million survivors of deceased workers.7 And the average life expectancy is currently more than 75 years and rising. 8

In 1998 there were three workers per retiree; by 2025 there will be only two workers per retiree.9 And workers currently pay a payroll tax of 12.4 percent of their income— 6.2 percent each from the employer and employee—up to $80,400, a number that grows annually. That makes a maximum annual contribution in 2001 of just under $10,000, or about a 1,600 percent increase since the program’s beginning.

Tax Increases in Our Future?

However, not even a $10,000 per worker maximum contribution will save the program in the future. According to the trustees’ report, the growing deficit means bringing Social Security into short-term actuarial balance could be achieved by either a 13 percent reduction in benefits or a 15 percent increase in the payroll tax, or some combination of the two.10 In order to ensure solvency for the next 75 years, a 50 percent increase would be necessary, to 18.5 percent of payroll.11

The IRA Model

One solution to the Social Security trust fund’s financial troubles is to allow workers to “pre-fund” their retirement needs by making contributions to a Personal Retirement Account. Indeed, many countries have already taken a step in this direction, with positive results.12

Americans Already Invest Their Retirement Money

Currently, some 42 million Americans manage most or all of their personal retirement savings through an IRA, or Individual Retirement Account. The law gives account holders wide discretion to invest their money in stocks, bonds, treasury notes, CDs or other financial instruments. While most Americans invest those funds fairly conservatively, such as in mutual or index funds that reduce their risk, even those funds took a financial beating over the past year.

Although the market may begin an upward trend soon, albeit at a slower pace than it rose at the end of the 1990s, the sharp market downturn raised concerns that market volatility may make Personal Retirement Accounts less politically popular.

Are Retirement Savings Accounts a “Risky Scheme”?

President Bush, most Republicans and some Democrats have called for a gradual transition from the current pay-as-you-go Social Security system to one centered around pre-funded accounts. Although polls show that the American public supports such a transition, recent stock market volatility has led PRA opponents to call them a “risky scheme.”13 That’s because virtually all plans to shift to PRAs are based on the IRA model which gives workers and retirees some discretion in how their retirement funds are invested. [See Figure 1.]

Figure 1

Although some PRA proposals would allow workers and seniors to make specific decisions about which stocks, bonds, mutual or index funds to invest in, others would restrict investment options to certain approved fund managers who would invest in broad-based index funds. But up until now, virtually all proposals for shifting Social Security to a system of Personal Retirement Accounts have assumed some form of direct market investment.

The Market Isn’t Risky, but Certain Years Are

Of course, there is nothing inherently wrong with the IRA model. Numerous economists have clearly demonstrated that stock market losses are offset by much larger gains. 14 Some years may be down, but as the U.S. economy grows, so will the stock market. Thus any strategy that envisions market investment over a worker’s life will see significant returns on the deposits.

However, PRA opponents have exploited the current market downturn as a way to incite public fear that a system of Personal Retirement Accounts would leave the retirement savings of workers and seniors vulnerable to catastrophic loss. Their efforts have led to a situation in which PRAs based on an IRA model may be doomed politically—at least for the foreseeable future. But is there a new model that provides good returns with virtually no risk? Yes, and it’s been around for 20 years.

The Galveston Model

In the late 1970s, officials in Galveston County, Texas, wanted to explore the possibility of leaving the Social Security system. Municipalities were not included in the original Social Security legislation in 1935. However, Congress passed legislation in the 1950s that let them join Social Security if they chose to do so.

Currently, about 5 million municipal employees (including those working for state, county and city governments and public school teachers) have their own retirement systems separate from Social Security. However, nearly all of them are defined-benefit plans similar to Social Security—although most of them are in much better financial shape—that pay retirees based on a promised benefit rather than on how much the employee contributed.15

Galveston County Judge Ray Holbrook contacted Rick Gornto, who worked in insurance and retirement planning, and asked him to devise a retirement plan that would replace Social Security. If Social Security were only a retirement plan, then creating an alternative that would provide better retirement income would have been fairly simple. However, Social Security is a system of social insurance that provides disability income and survivors’ benefits. From the outset, Mr. Gornto’s goal was to create a private alternative to Social Security that essentially mirrored Social Security’s covered areas but provided better benefits.

Employees of Galveston County believed he succeeded and in 1981 voted by a margin of 72 percent to 28 percent to leave the Social Security system and move to pre-funded, personally owned accounts. In 1982 Matagorda and Brazoria Counties followed suit. But in 1983 Congress removed the provision, meaning no more municipalities could opt out.16

Not Your Father’s Social Security

Workers in the Galveston County plan, which is referred to as the “ Alternate Plan,” pre-fund their retirement accounts.17 The money they deposit grows with interest over their working careers. When they retire they get the money in the account, not a monthly allotment based on some government-created formula as those who receive traditional Social Security do. If workers die before they retire, money in the account becomes part of their estate. In addition, workers are covered with life insurance and disability insurance—similar to Social Security, only much better.18

Currently, there are about 2,740 full-time employees participating in the Galveston Model, or Alternate Plan. Originally, participating employees and employers contributed the same 12.4 percent of income (6.2 percent each from the employee and employer) that other workers pay in Social Security payroll taxes. However, over the years Galveston County has increased its contribution by about 1.5 percentage points so that its employees will have even more in retirement savings.

Of course, no company would do that for employees who are in traditional Social Security because those employees wouldn’t receive the additional money. For the three Texas counties, an increase in the employer contribution is equivalent to a pay raise or an increase to the employees’ pension plan.

More Retirement Money and Better Benefits

In Galveston employees contribute 6.13 percent of their income while the county pays 7.785 percent (though it only has to pay 6.2 percent). The combined 13.915 percent is dispersed as follows:

• Retirement Annuity 9.737%

• Survivorship Benefit 2.850%

• Long-term Disability 1.180%

• Waiver of Premium 0.148%

But while the money taken from the employee and employer is essentially the same as in Social Security, the benefits are dramatically different.19

Retirement Annuity

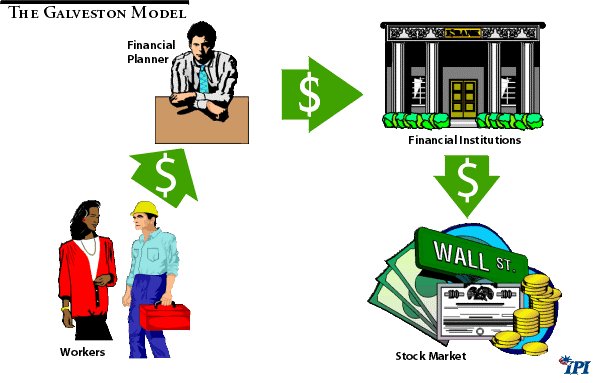

Workers contribute 9.737 percent of their income toward retirement savings. The company that manages the Alternate Plan, First Financial Benefits, pools the money from all of the employees and loans it to a top-rated financial institution for a guaranteed interest rate. [See Figure 2.] Those rates have varied from around 5 percent up to 15.5 percent, but average in the 7.5 percent to 8 percent range.20 Thus, employees bear virtually no risk; they get their interest whether the stock market goes up or down—and they have done so for 20 years. Nor are employees making investment decisions. Professional money managers do that for them. This process works much more like a bank than an investment brokerage. And, for all intents and purposes, the money is as safe as if it were in a bank.

Figure 2

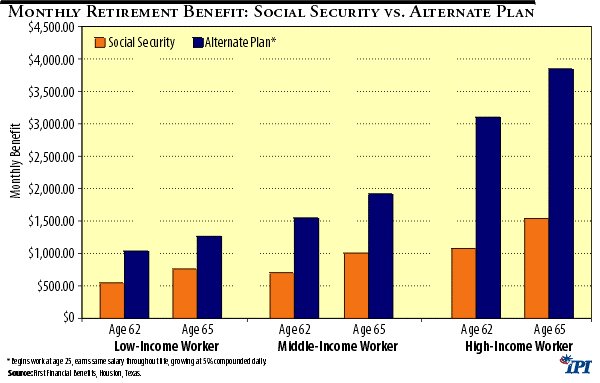

Even so, the Alternate Plan has proven to be very rewarding financially. As Chart 1 shows, even if employees’ deposits only grow at 5 percent (most years they have had higher interest rates), they can expect to get about twice as much in retirement as they could expect from Social Security, according to First Financial:

Chart 1

• A low-income worker ($17,124) retiring at age 62 could expect to receive about $547 per month from Social Security versus $1,035 per month from the Alternate Plan. Someone retiring at age 65 would get $782 per month from Social Security, but $1,285 from the Alternate Plan.

• A middle-income worker ($25,596) retiring at 65 can expect $1,007 a month from Social Security, or $1,920 from the Alternate Plan.

• And the high-income worker ($51,263) at 65 will get $1,540 from Social Security versus $3,846.21

Upon retirement, workers can take their money in a lump sum or purchase a variety of annuities that will pay them a guaranteed income for life.22 It’s their money, so it’s their choice.

Moreover, since the accounts and the funds therein actually belong to the employees, they become part of their estate regardless of when they die. Workers in traditional Social Security who die before retirement lose virtually all of their contributions.

Survivorship Benefit

Upon death, Social Security pays a surviving spouse a one-time death benefit of $255. The Galveston Model includes a life insurance policy that pays three times a worker’s salary, between a minimum of $50,000 and a maximum of $150,000—and the policy pays double if the worker dies accidentally. The insurance payout declines after retirement, but the plan still pays more than most survivors would get under Social Security.

By contrast, Social Security will pay survivors’ benefits under specific conditions such as a spouse who only qualified for Social Security by virtue of being married to a deceased worker, and then only after 60 years of age. But the spouse must remain unmarried to qualify.

Under which plan, Galveston or Social Security, will survivors do better? That depends.

Consider, for example, a 40-year-old married male with two children, both age 10, who worked for the county since he was 22. The family of a $30,000/year employee who died at 40 could expect to receive a death benefit or $60,000 (three times his salary) and his account balance of approximately $57,285, according to First Financial Benefits. Were that money combined and placed in an 8-year annuity (paying until the children reached age 18, as under Social Security), the family could expect to receive about $2,162 per month. According to the Social Security Administration, the average monthly survivorship benefit for a widow/widower with two children is $1,696 per month.

However, the family of a low-income worker who had not been with the county very long and with very young children would likely do better under Social Security.

Long-Term Disability

Workers who have participated for 20 quarters (i.e., a total of five years) in the traditional Social Security system and become disabled are allowed to draw disability benefits until they return to work or reach retirement age.23

By contrast, a worker under the Alternate Plan is eligible for disability benefits the first day on the job (though workers under both plans have to wait 180 days after becoming disabled to receive benefits).24

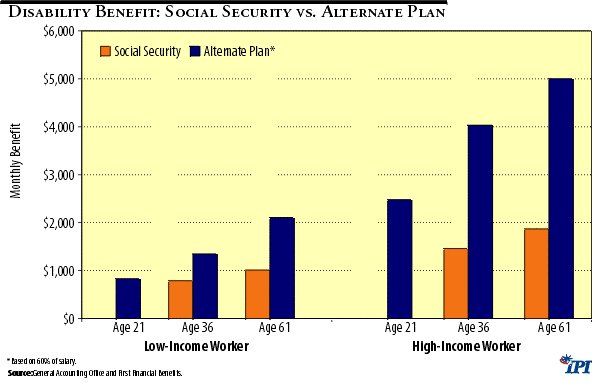

Moreover, according to the General Accounting Office (GAO), workers in the Alternate Plan can expect to draw significantly more money than those who must rely on Social Security disability benefits. Under the Alternate Plan, workers will receive 60 percent of their salary up to a maximum of $5,000 a month until they return to work or turn age 65. According to the GAO:25

• A 21-year-old, low-income disabled worker on Social Security would get no disability benefits, while a worker in the Alternate Plan would get $829 a month. A 36-year-old low-income disabled worker would get $788 from Social Security versus $1,346 from the Alternate Plan. And a 61-year-old could expect $1,013 a month from Social Security as opposed to $2,106 under the Alternate Plan.

• A 21-year-old, high-income disabled worker on Social Security would get no disability benefits, while a worker in the Alternate Plan would get $2,479 a month. A 36-year-old high-income disabled worker would get $1,459 from Social Security versus $4,030 from the Alternate Plan. And a 61-year-old could expect $1,869 a month from Social Security as opposed to $5,000 under the Alternate Plan. [See Chart 2.]

Chart 2

In addition to receiving more income, disabled workers in the Alternate Plan can use the money in their retirement accounts if needed. Social Security has no equivalent benefit.

But wouldn’t drawing down the cash in the account leave a disabled worker broke at retirement? Creators of the Galveston Model figured out a way to address that problem.

Waiver of Premium

For those who become disabled and cannot contribute to their accounts, the Alternate Plan includes a waiver-of-premium insurance policy that picks up employees’ deposits to their retirement accounts.

Is Everyone Better Off in the Alternate Plan?

Rick Gornto’s goal in devising the Alternate Plan was to create a program that substantially matched what Social Security covered, while providing better benefits. Although some differences remain, he achieved that goal.

Is everyone better off in the Alternate Plan than in Social Security? Not necessarily. Certain people in certain circumstances might be better off in the current Social Security system.26 For example, Social Security provides a lifetime annuity to a surviving spouse after age 60 or until children reach the age of 16.27 By contrast, the beneficiary (a spouse and/or children) of someone in the Alternate Plan can take a lump-sum distribution of the account or purchase an annuity, essentially mirroring Social Security’s monthly payments. Under certain circumstances—such as living a very long time—it is possible that a surviving spouse would get more money under Social Security.

In other words, critics of Retirement Savings Accounts will doubtless be able to contrive scenarios in which an individual would be better off in traditional Social Security, in part because of the various qualifications and restrictions that are part of both plans. But in the vast majority of circumstances people will be markedly better off under the Alternate Plan than under Social Security.

The Need to Protect Savings against Risk

Critics of Personal Retirement Accounts constantly raise the accusation that letting people manage their retirement savings would be a “risky scheme.” They imply that people would be “day-trading” with their retirement savings, investing them in high-risk stocks or relying on rumors in hopes of huge gains.

While there are some people who would do that if given the option, virtually no serious IRA model reform proposal would give account holders that degree of freedom. More likely, workers would be restricted to approved index funds or fund managers.

In fact, there is a growing concern that many Americans managing their own 401(k) retirement funds may be getting sub-optimal returns not because they are too aggressive, but because they allocate their assets too conservatively. 28 There are countless investment options and strategies. Knowing when and how much to invest are not easy decisions, which means there is lots of room for bad decisions. To the extent that untrained workers and retirees control asset allocation in their personal accounts, they could well see their accounts decline instead of increase.

Is there a solution to avoiding this risk? Yes. One way is to make sure that PRA funds go into broad-based index funds that grow—and occasionally shrink—with the economy. Another way is to set aside the “investment model” that envisions direct market investment and shift to a “ banking model” that functions more like a savings account—hence, a Retirement Savings Account rather than a Personal Retirement Account.

The Banking Model

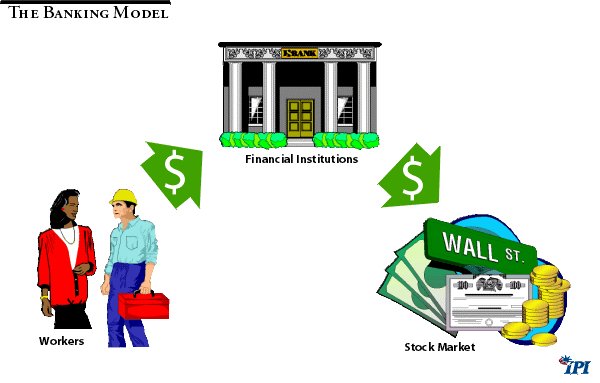

The three Texas counties that have had Retirement Savings Accounts for 20 years have a successful retirement program based on a banking model rather than an investment model. As Figure 3 shows, workers are not required to make decisions about where to invest their funds; that decision is made by professional money managers. And because the financial institution that borrows the money guarantees a minimum return, workers don’t lose money when the stock market goes down. If the market slides, the financial institution bears the loss, not the employees.

Figure 3

Can the Galveston Model, which has provided near-market returns for 20 years, be adapted to a national plan? The answer is yes.

Let Banks Be Banks

There is nothing new about Americans entrusting their savings to financial institutions that guarantee them a fixed return. That is, in essence, what the three Texas counties do, relying on First Financial Benefits to act as a middleman to bring together all the necessary ingredients: life and disability insurance and the highest available interest rate.

However, if the Galveston Model were expanded nationwide, some elements of the model would no longer be necessary. For example, there would be no need for an intermediary to bring together all the elements. Banks and other financial institutions themselves could create a retirement package that included life and disability insurance, along with a guaranteed interest rate. Instead of using a financial manager to pool the funds, individuals could take their money directly to the financial institution of their choice.

Let Other Financial Institutions Be Banks

Although the Galveston Model is a banking model, that doesn’t mean that banks should be the only financial institutions allowed to participate. Insurance companies, brokerages and investment firms also should be included. Any financial entity that meets certain federal government standards should have the opportunity to compete for workers’ and retirees’ RSAs.

Near-Market Rates of Return

The stock market exploded in the late 1990s, but that was not the normal pattern. Between 1950 and 1995, the average annual return on the stock market was 12.42 percent and 4.14 percent for bonds. 29 Between 1900 and 1995, it was 13 percent for stocks and 11.34 percent for bonds.30 RSAs will not get that type of return, but in a competitive environment they might get relatively close. The Alternate Plan has often negotiated 8 percent or more—very high considering there is almost no risk of participants losing their principal.

Let the Competition Begin

Consider the competition that would ensue from the banking model. RSAs would be large, illiquid pools of money—several hundreds of thousands of dollars for older workers—that would be extremely attractive to financial institutions. Participating institutions should be allowed to attract new accounts by offering the highest interest rate possible—and those that are most efficient and successful at managing their funds would likely offer the highest interest rates. While account holders would not be able to withdraw portions of their funds, they should be allowed to move them to another financial institution.31 And, of course, financial institutions should be allowed to offer higher interest rates in return for a guarantee to leave the funds with the institution for a specified period of time.

Administrative costs imposed on RSAs under this approach would be minimal and would likely be absorbed by the financial institution, just as there are no fees on most checking accounts that maintain a minimum balance. Banks are willing to waive those fees in order to have the money in the bank. That would be even more true with RSAs.

What Would Be the Role of Government?

The federal government would likely play a regulatory role in RSAs just as it does with banks. That role should include setting basic minimums on insurance coverage. It might also set certain institutional minimums such as reserve requirements, and it might require certain accounting standards and other process-oriented minimums. Finally, the government would likely have to guarantee deposits, just as it does for banks through the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC).

But the federal and state governments already handle these functions today with banks and savings and loans. Those regulations might have to be tweaked to fit RSAs. But the point is our economy and financial institutions have a long history of successfully addressing these concerns.

However, while the government may need to set minimums, it should not set maximums. Interest rates and insurance coverage should be allowed to go as high as the market and efficient financial institutions can provide.

Why a Banking Model Addresses Concerns about RSAs

Critics of Personal Retirement Accounts based on an IRA model have raised a number of concerns over the years. Some of those concerns are valid, others aren’t. However, Retirement Savings Accounts based on a banking model would satisfy almost all of the objections.

It Is Not a “Risky Scheme”

Critics of PRAs paint a picture of daytraders “gambling” with their retirement savings. Although that concern has always been overblown, it is true that under some IRA model proposals people would be making some allocation decisions. It is also true that the vast majority of Americans are relatively unsophisticated investors and are reluctant to take the time to learn more about it.

More importantly, a shift from traditional Social Security to RSAs should not force people who have neither the desire nor the skills to become investors. By moving from an investing model to a savings model, we remove that problem. People would decide where to put their money, but professional money managers would handle all investments.

Administrative Costs Would Be Low

The debate over the cost of administering PRAs has also been extensive. According to Social Security’s trustees, the cost of administering the OASI program was 0.6 percent of total expenditures, while DI’s administrative cost was 2.9 percent of expenditures.32 Critics have claimed that private-sector administrative cost would be much higher—a notion that has been aggressively challenged by PRA supporters. 33

However, in most cases banks internalize administrative costs rather than pass them on to the consumer. Banks make their money on the spread between what they pay on a deposit and what they can make investing that money, and in most cases they cover their administrative costs out of that spread. That approach would likely apply to RSAs based on a banking model.

Accounts Would Spur Competition to Provide the Highest Guaranteed Interest Rate

Since banks offer fairly low interest rates on CDs and other “safe” investments—about 3 to 3.5 percent—wouldn’t that rate be too low to provide the kind of growth future retirees need?34

That’s why it is necessary for financial institutions other than banks to participate. First Financial Benefits has successfully secured much higher interest rates for Alternate Plan participants than one would expect from a CD by letting companies compete for the money. Financial institutions want large pools of illiquid money, and they would have an incentive to bid up the interest rates as high as possible to get that money.

In fact, that shift is already occurring. The New York Times recently reported that banks are becoming more competitive. “Banks, after years of neglecting small savers, are trying a number of gimmicks to win back such customers. Some are offering free checking or higher rates on money market accounts. Others are pushing more convenient hours and better service.” 35 It should be noted that offering “higher rates” is not a gimmick as the Times states, but if banks are willing to compete for small savers, think what they will do for RSAs.

Furthermore, although the banking model as presented here envisions financial institutions trying to lure individual account holders, nothing should prohibit an employer or financial planner from working with financial institutions to create larger pools of people—such as members of a credit union, association or fraternal organization—which might spur even better interest rates.

It Would Increase the Savings Rate

We frequently hear laments of how little Americans save. For example, according to a recent report, the U.S. savings rate went in the negative range (-0.1 percent) for the first time since 1933.36 It was at its highest in 1945, when it was 20.6 percent.37

In a sense those concerns are disingenuous since the government is taking 12.4 percent of workers’ earnings to provide a minimal level of retirement income. But that money isn’t considered “savings” since Social Security is a social insurance program, not a savings account. However, if that payroll tax were deposited in a savings account that actually belonged to the worker, it would then be part of the savings rate. More importantly, these savings would be “real” savings—real wealth accumulation, not a promised government entitlement.

Accounts Would Be Personal Property

Because Social Security is a social insurance program rather than an investment or savings account, people have no private-property right in the account, according to the U.S. Supreme Court.38 Although it would be politically difficult to do, Congress could eliminate benefits or cancel the program altogether.

RSAs, by contrast, would belong to each worker and retiree. Workers would have a private-property right in the account and no one could take it from them without due process of law.

Unspent Balances Would Pass to Heirs

Because workers would have a private-property right in their accounts, unspent balances would become part of their estate at death. The importance of this point cannot be overstated. Although Social Security provides survivorship benefits under specific conditions, in most cases workers who die before the age of 65 get virtually nothing from their lifetime of continuous contributions. A number of studies have demonstrated that this provision adversely affects groups that tend to have shorter life spans, such as black and Hispanic males.39 Regardless of when a worker or retiree dies under the Alternate Plan, any balance in the RSA goes to the heirs.

Plan Would Include Life and Disability Insurance

Most proposals for personal accounts do not include a life or disability insurance provision. They would only allow people to set aside a portion— in most cases, a relatively small portion—of their payroll tax. While these accounts would surely help workers set more money aside for retirement, they are not an alternative to Social Security because they don’t match the benefits. In effect, these accounts are an add-on to the Social Security program, not a substitution for it.

When Rick Gornto created the Alternate Plan, he thought it should mirror the Social Security program, only with more generous benefits. Any proposal to create RSAs on a national scale should do the same, which is why an RSA based on a banking model is the best approach. Financial institutions such as Prudential, Fidelity, Merrill Lynch and Bank of America might well go into partnerships with New York Life or Mutual of Omaha in order to create a package product that mirrors the Social Security program.40

Participation Would Be Optional

When Galveston County employees voted to leave Social Security, they had to leave as a group. However, under a nationwide program participation should be optional. Those who want to remain in traditional Social Security should be allowed to stay.

No Penalty for Early Retirement

In 2000, Congress took an important step for both seniors and the economy: it voted unanimously, in both the House and Senate, to end the Social Security earnings limit for seniors age 65 and older. The earnings limit penalizes retirees who earn more income than the government allows by withholding a portion of their Social Security benefits.

However, workers age 62 through 64 who decide to take early retirement are still penalized with an earnings limit tax that is even more onerous than the one Congress eliminated. Early retirees who continue to work will have their Social Security benefits reduced $1 for every $2 they make above the $10,680 limit in 2001—an effective 50 percent marginal tax rate.41

Because Social Security is a pay-as-you-go program, the timing of a worker’ ;s retirement is not only a personal decision but a political issue: retirement incurs an economic liability on the rest of society, which must provide the promised benefits.

Under a system of RSAs, by contrast, workers would be free to retire whenever they choose—or when they are forced to do so by an employer who pushes them into early retirement—without being penalized. If retirees fund their retirement from their own accounts, who cares when people retire?

Participating Financial Institutions Would Have Federal Backing and Oversight

Banks, insurers and other types of financial institutions operate under a government regulatory framework meant to protect consumers and their money. A system of RSAs would likely operate under a similar framework. For example, the federal government requires banks to purchase insurance from the FDIC to cover depositors’ losses in case of a bank failure. A similar type of guarantee, either through the FDIC or another organization, would be both politically and economically necessary for those shifting to RSAs.

Addressing the Transition Costs

One of the most important questions facing Social Security reform is the cost of transitioning from a pay-as-you-go system to a pre-funded system. Projecting that cost is extremely difficult because it depends on how many people switch to RSAs and the conditions under which they switch.

Transition costs weren’t a factor for the three Texas counties; they just switched. Those who had paid into Social Security would get part of those benefits, along with their RSA balances. But transition costs are a common denominator of any pre-funded account, not just a banking model. While this paper takes no position on how the transition should be funded, it is clear that once an RSA approach has been determined, we will have to have a healthy public policy debate on the best way to pay for the transition.

Wait Now, Pay Later

Several things can be said about transition costs with some certainty. First, the cost of transition only grows the longer we wait. If it will be costly today, it will be even more costly tomorrow. Nothing is gained economically by waiting.

Second, both the Social Security trust fund and general revenues are facing surpluses for the next several years. That opens a window of opportunity to begin the transition to RSAs and to fund the transition costs with either the Social Security surplus or general revenues.

The Surplus for Us

Will the surplus be enough to fund the transition costs? Perhaps, but it depends on several factors. For example, under legislation proposed by Rep. Pete Sessions (R-Texas), those who chose to shift to RSAs would give up 20 percent of their claim to benefits due them for each year they are in the private system. Thus, in five years an RSA holder would have no further claim on payroll taxes already paid into Social Security. According to the number of people choosing RSAs under that proposal, it could have a significant impact on Social Security’s future obligations.

One for You; Two for Them

Another question is whether people who switch to RSAs would continue to pay into the traditional system. Previous proposals by Sen. Phil Gramm (R-Texas) and former Rep. Bill Archer (R-Texas) allowed people to place only 2 or 3 percentage points of their payroll tax into RSAs. Thus, about 9 to 10 percentage points would still go to fund traditional Social Security, including the disability and survivorship provisions of the program.

Two for You; One for Them

Were the Galveston Model expanded nationwide, most of the payroll tax should go to the employees’ RSAs, especially since both the disability and life insurance provisions would be funded out of the workers’ contributions.

One way to address the problem of transition costs is to vary the Social Security contributions of those who opt out of the system. For example, those just entering the workforce might be required to put several percentage points—say, 5 percentage points—into the old system to help keep it solvent for future retirees. Those in early middle age—say, 35 to 45 years of age—could be required to contribute perhaps 2 or 3 percentage points. And a middle-age worker opting for RSAs might not be required to contribute anything to maintaining the current Social Security system—especially if they give up their claim on previous deposits as discussed above. A recent study by economists Martin Feldstein and Elena Ranguelova found that given a 5.5 percent rate of return, only 3.1 percent of payroll would be needed to fund the “benchmark” benefits (i.e., equivalent to the current system). 42

All of these factors will play a role in who would switch to RSAs and who would remain. It is possible, depending on the legislation and how people react to it, that the surplus will fund the transition. But even if it doesn’t or can’t, Congress should commit itself to funding whatever is necessary to make the transition work—even if that means borrowing the money to meet the shortfall.43

Conclusion

For several years the debate over reforming Social Security has centered on an IRA model, in which people’s contributions rise or fall with the stock market—or even individual stocks. That model works in other countries and it can work here. However, stock market volatility and political posturing may make that option politically impossible.

Fortunately, there is an alternative. Thousands of Texans have had Retirement Savings Accounts for 20 years and never lost a dime. Today, they are retiring with thousands of dollars more than they would have had had they remained in Social Security all of their working lives.

Can RSAs work? They already do. We have a model with an excellent track record. It is time to stop looking at those three Texas counties with envy, and look at them as a model for no-risk Retirement Savings Accounts for every American.

Endnotes

1. David Wessel, “The Wealth Effect Goes into Reverse,” Wall Street Journal, May 24, 2001.

2. Estimates vary on what Social Security’s rate of return is and depend on a number of assumptions. See the discussion in William W. Beach and Gareth Davis, “Social Security’s Rate of Return,” Heritage Foundation, A Report of the Heritage Center for Data Analysis, No. 98–01, January 15, 1998. The authors estimate that “Social Security’s inflation adjusted rate of return is only 1.23 percent for an average household of two 30-year-old earners with children in which each parent made just under $26,000 in 1996.”

3. John L. Pabner and Thomas R. Saving, “The 2001 OASDI Trustees Report,” ; Social Security Administration, March 19, 2001.

4. See David C. John, “The Social Security Right to Know Act: Telling the Truth About the Future,” Heritage Foundation Backgrounder No. 1371, May 19, 2000.

5. Pabner and Saving, “The 2001 OASDI Trustees Report.”

6. Peter J. Ferrara and Michael Tanner, A New Deal for Social Security, Washington, DC, Cato Institute, 1998, p. 38; and Commission to Strengthen Social Security, "Bringing Scoial Security into the 21st Century," Draft, July 18, 2001.

7. “Fast Facts and Figures about Social Security,” Social Security Administration, August 2000, p. 14.

8. Ferrara and Tanner, p. 39.

9. Ibid., p. 41.

10. Pabner and Saving, “The 2001 OASDI Trustees Report.”

11. Ibid., p. 44.

12. See Ferrara and Tanner, Ch. 7.

13. See Thomas Sowell, “Social Security – A ‘Risky Scheme,’ ” Capitalism Magazine, October 26, 2000; and Lawrence B. Lindsey, “Gore’s Risky Social Security Scheme,” Wall Street Journal, July 13, 2000.

14. See Jeremy Siegel, Stocks for the Long Run, Chicago, Irwin Professional Publishing, 1994; and Ferrara and Tanner, Ch. 4.

15. See Carrie Lips, “State and Local Government Retirement Plans: Lessons in Alternatives to Social Security,” Cato Institute, SSP No. 16, March 17, 1999.

16. That doesn’t mean that other municipalities wouldn’t like to opt out. Rick Gornto has had numerous contacts over the years from other government entities that would like out of Social Security.

17. It was called the “Alternate Plan” at its inception because it was an alternative to traditional Social Security.

18. For a summary of benefits, see, “A Summary of the Alternate Plan for Galveston County Employees,” First Financial Benefits, Inc., revised 2001.

19. Because the Alternate Plan comes under pension law, the maximum annual contribution is $8,500.

20. When the General Accounting Office examined the Alternate Plan in 1999, it concluded that interest rates “ranged widely” but “currently are around 6 percent in nominal terms.” “Social Security Reform: Experience of the Alternate Plans of Texas,” General Accounting Office, GAO/HEHS-99–31, February 1999, p. 9.

21. While $51,000 a year will not seem to many people like a “high-income worker,” these are county (government) employees. The income levels were established by the GAO report.

22. Of course, if retirees decide to purchase an annuity, they can keep any balance over the cost of the annuity.

23. If a disabled worker is under age 31, he must have had earnings in at least half of the quarters since turning 21.

24. For a discussion of the qualification criteria, see “Social Security Reform: Experience of the Alternate Plans of Texas,” p. 12.

25. “Social Security Reform: Experience of the Alternate Plans of Texas,” p. 24.

26. The GAO study concluded: “Our simulations of how workers for the three Texas counties and their dependents might fare under the two systems revealed that outcomes depend generally on individual circumstances and conditions. In general, we found that certain features of Social Security, such as the progressive benefit formula and the allowance for spousal benefits, are important factors in providing larger benefits than the Alternate Plans for low-wage earners, single-earner couples, and individuals with dependents.” “Social Security Reform: Experience of the Alternate Plans of Texas,” ; p. 3. However, Rick Gornto felt the GAO study did not give sufficient weight to certain elements of the Alternate Plan and wrote a response to the GAO study. See “First Financial Benefits Responses to Individual Provisions in the GAO and Social Security Briefs,” January 15, 1999.

27. “Social Security Reform: Experience of the Alternate Plans of Texas,” p. 12.

28. See, for example, Bill Deener, “Market Reveals 401(k) Naivete,” Dallas Morning News, May 14, 2001; and Bill Deener, “Workers Choose 401(k) Managers,” Dallas Morning News, May 21, 2001.

29. Ferrara and Tanner, A New Deal for Social Security, p. 74.

30. Ibid.

31. Some restrictions may need to apply because of the life and disability insurance components so as to minimize or avoid adverse selection, in which one plan gets a disproportionate number of bad risks.

32. Pabner and Saving, “The 2001 OASDI Trustees Report.”

33. See Robert Genetski, “Administration Costs and the Relative Efficiency of Public and Private Social Security Systems,” Cato Institute, SSP No. 15, March 9, 1999.

34. At this writing, 3-month Treasuries are offering 3.59 percent and bank CDs are at 3.30. However, 5-year brokered CDs are at 5.74 percent. See Scott Burns, “Credit Unions a Good Option for Investment Income,” Dallas Morning News, May 29, 2001.

35. Riva D. Atlas, “Many Banks Think the Time Is Ripe to Lure Savers,” New York Times, May 4, 2001.

36. K. C. Swanson, “Why Is the Personal Savings Rate Negative for the First Time Since 1933?,” TheStreet.com, February 28, 2001. See also Stephen J. Entin, "Fixing the Saving Problem: How the System Depresses Saving, and What to Do About It," Institution for Policy Innovation, in conjunction with the Institute for Research on the Economics of Taxation, Policy Report No. 156, May 2001.

37. Ibid.

38. See Charles E. Rounds Jr., “Property Rights: The Hidden Issue of Social Security Reform,” Cato Institute, SSP No. 19, April 19, 2000.

39. See W. Constantijn, A. Panis and Lee Lillard, “Socioeconomic Differentials in the Return of Social Security,” RAND Corporation Working Paper Series No. 96.05, February 1996, and Beach and Davis, “Social Security’s Rate of Return.”

40. If including both life and disability insurance for those who opt out is too big a step initially, RSAs should at least include life insurance to cover the survivor’s provision. That would leave the current Social Security program as the disability safety net.

41. See Merrill Matthews Jr., “Ending the Social Security Earnings Limit— for Everyone,” Institute for Policy Innovation Issue Brief, April 3, 2001.

42. Martin Feldstein and Elena Ranguelova, “Individual Risk in an Investment-Based Social Security System” National Bureau of Economic Research, Working Paper 8074, January 2001.

43. For a discussion of why borrowing money to cover the transition costs is a good option, see Lawrence A. Hunter and Steve Conover, "Who's Afraid of the National Debt?: The Virtues of Borrowing as a Tool of National Greatness," Institute for Policy Innovation, Policy Report No. 159, July 2001.

About the Author

Merrill Matthews Jr., Ph.D., is a public policy analyst specializing in health care, Social Security and other domestic policy issues, and has published numerous studies addressing those issues both at the national and state levels. He is past president of the Health Economics Roundtable for the National Association for Business Economics, the trade association for business economists, and a health policy advisor for the American Legislative Exchange Council, a bipartisan association of state legislators.

Dr. Matthews serves as the medical ethicist for the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center’s Institutional Review Board for Human Experimentation and has contributed chapters to two recently published books: Physician Assisted Suicide: Expanding the Debate (Routledge, 1998) and The 21st Century Health Care Leader (Josey-Bass, 1998).

He is a Brain Trust columnist for Investor’s Business Daily and has been published in numerous scholarly journals and newspapers, including the Wall Street Journal, Barrons and the Washington Times . He is the political analyst for the USA Radio Network and a frequent commentator for National Public Radio.

Dr. Matthews received his Ph.D. in philosophy and humanities from the University of Texas at Dallas.