The Republicans in the House, however, would not touch the measure, and it never became law. But in the 1986 elections, Democratic challengers ran ad after ad against the Republicans who had voted for it. The vote had seemed so reasonable in the summer of ’85, when all the economists were telling the Republican senators it was economically sound to make the change. But in the heat of political battle a year later, the issue was quite different. The Republicans lost eight Senate seats that year reducing their numbers from 53 to 45 and losing control of the Senate after first winning it in the Reagan landslide of 1980.

Today, the President is suggesting a much larger benefit adjustment than the 1985 Senate COLA reforms. A coalition of business lobbyists, think tank analysts, and even the Bush Administration is urging a switch in the calculation of basic Social Security benefits from a wage-indexed to a price-indexed basis. But is this either economically or politically a wise move?

A Huge Cut in Future Promised Benefits

Under the current system, during a taxpayer’s working years, the future benefits that are to be paid to the worker increase each year at the rate of growth of wages. As a result, with both income and Social Security benefits growing with wages, the Social Security replacement rate, or the percent of pre-retirement income replaced by So Under the current system, during a taxpayer’s working years, the future benefits that are to be paid to the worker increase each year at the rate of growth of wages. As a result, with both income and Social Security benefits growing with wages, the Social Security replacement rate, or the percent of pre-retirement income replaced by Social Security, remains the same over time. Currently, Social Security replaces about 40% of pre-retirement income for average income workers, and 28 percent for higher-income workers.

Price indexing would change the calculation of future Social Security benefits, so while a taxpayer is working, the future benefits to be paid to the worker would increase only at the rate of growth of prices. This would freeze Social Security benefits at today’s levels in real terms. It would be a massive reduction in the Social Security benefits that would be paid in the future under current law, so massive that it would be enough by itself to eliminate the long-term Social Security deficit entirely.

For today’s young workers, future Social Security benefits promised under current law would be reduced by 30 percent to 40 percent from the levels that otherwise are scheduled to be paid. As time goes on, and as benefits continue to grow more slowly than wages, this cut from currently promised benefit levels would become larger and larger, eventually reaching 50 percent, and continuing on even higher.

Some argue that this cut is appropriate. According to them, since wages grow about 1 percent more than prices each year, current law linking benefits to wage growth provides for an unjustified increase in real benefits over time, an increase of 40 percent by the time today’s young workers retire. Advocates of this approach argue that with huge future deficits in the program, this scheduled increase is irresponsible and unfair to future workers. But this argument is not fully informed, and, therefore, misleading.

For one thing, payroll taxes grow at the rate of growth of wages over time, as do other taxes. Is it unjustified or unfair to expect benefits to at least grow at the rate of growth of wages as well?

Even with benefits growing along with wages as under current law, the rate of return Social Security pays is still meager and inadequate. It is the current, wage-indexed benefits of the current system that advocates of personal accounts have long criticized as providing inadequate, below-market returns. Even with the current wage indexed benefits, Social Security’s rate of return for most workers today is 1 to 1.5 percent or less. For many it is zero or even negative. 1

But under price indexing, with taxes growing at the rate of growth of wages and benefits growing only at the rate of growth of prices, the rate of return paid by Social Security would decline each and every year in perpetuity! Workers would all be forced down into the negative range, and then deeper and deeper into that range, over time. This would be grossly unfair to future workers. Consequently, price indexing is not a solution to the current system’s problems. It only makes those problems worse, by making the program even more of a bad deal than it already is.

In addition, under price indexing, with incomes naturally growing with wages but benefits only growing with prices, the Social Security replacement rate would decline each and every year again in perpetuity! The replacement rate would decline to 30 percent, then 25 percent, then 20 percent by the time today’s young workers retire. It would then continue to decline, to 10 percent, to 5 percent, over time asymptotically approaching zero.

This is why at a recent conference in Washington, Cato Institute Social Security analyst Jagadesh Gokhale was asked by the moderator, “Isn’t it true that under price indexing Social Security benefits are eventually reduced to insignificance?” Gokhale being both intelligent and honest gave a completely accurate one-word answer, “Yes.”

Of course, all of this shows that price indexing, already unnecessary from a policy standpoint, will ultimately be politically indefensible as well. Reducing Social Security benefits to insignificance is not a good theme for the reformers. What may seem reasonable in the fever swamps fostered by chest-thumping Washington analysts today will likely seem ridiculous on the campaign trail in 2006.

New Twist, More Problems

In recognition of the validity of the above criticisms, the policy discussion has now shifted to giving the bad deal of price-indexing only to middle- and upper-income workers, or “progressive price indexing.” Under this proposal, the current wage indexing system would continue to apply to workers making less than $25,000 per year. The full price indexing system described above would apply to all workers making over $113,000 per year. For workers between $25,000 and $113,000 per year, a mix of wage indexing and price indexing would apply, with more price indexing and less wage indexing as income rose.

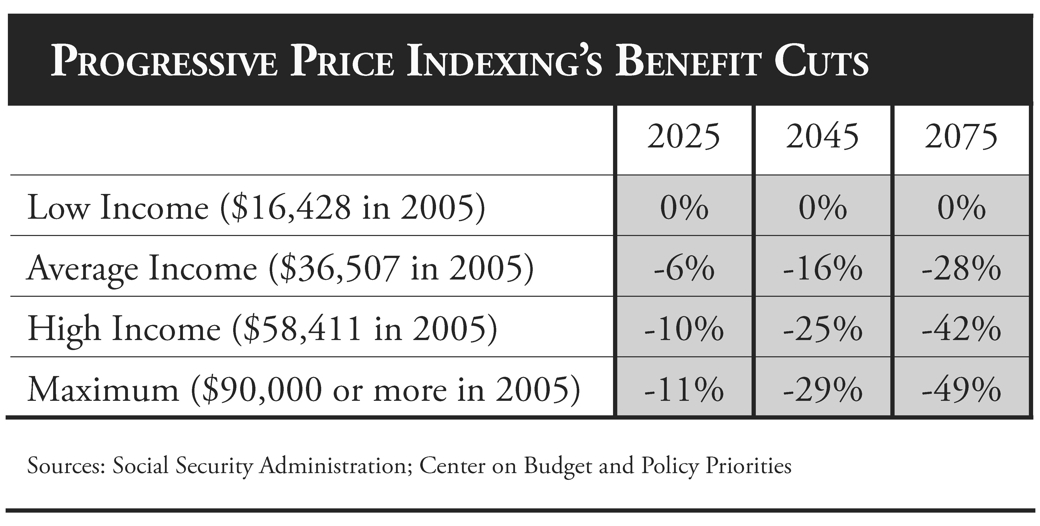

But all of the previous criticisms of price indexing would continue to apply for everyone making over $25,000 per year. The impact would just be phased in more slowly for workers earning between $25,000 and $113,000 per year. But their benefits would still be growing more slowly than their taxes, reducing the rate of return each and every year. Their benefits would also still be growing more slowly than their incomes, reducing the replacement rate each and every year. The same long-term cut in the current promised level of benefits would still eventually be reached for everyone earning above $25,000. The table below, based on data from the Social Security Administration, shows how big the cuts would be.

|

In addition, there are further intractable political problems any time we wade into trying to cut future promised benefits. Opponents of Social Security reform will respond to any such benefit cut proposals by insisting that “we can’t close the long-term Social Security financing gaps by dealing only with the benefit side.” They will insist that the package has to involve tax increases to go with the benefit changes. Republicans in Congress will want to have bipartisan support for the reductions in future promised benefits. To get that, they will go along with the tax increases. So anyone who supports adding cuts in future promised benefits to personal account reform is, in effect, supporting or at least paving the way for the tax increases that would inevitably have to go along with benefit cuts.

Once we are in the swamp of benefit cuts and tax increases, the personal accounts will become a bargaining chip that Republicans will probably give up in the end to get Democrat cover for the package. The Democrats have insisted that they will never support personal accounts that substitute for part of the current Social Security system. They have said they will support only add-on accounts that operate with contributions and benefits outside of and on top of the current system.

Such add-on accounts, however, do nothing to solve the problems of Social Security. Workers would still be suffering the bad deal and low returns and benefits the current Social Security system offers them, made all the worse if taxes are also raised and future benefits cut. Moreover, add-on accounts do nothing to eliminate the long-term deficits of Social Security, as real accounts would do as described below. Finally, real accounts offer an historic opportunity for massive reductions in taxes and government spending, all while making workers better off. The add-on accounts, however, have no such effects, and so fumble away this historic opportunity.

Nevertheless, Republicans would need bipartisan support for a package of large reductions in future promised benefits as well as large increases in taxes. So they will likely have to cave in on the real accounts to get Democrat support. That is where we will end up once we turn Social Security reform into the old game of negotiating a package of tax increases and benefit cuts.

The Graham Example

Indeed, this is exactly what is already happening. Senator Lindsey Graham’s public comments show precisely this, as they reflect what he has heard from Democrats. Graham started out falling for the idea that the way to get Democratic support for personal accounts was to include cuts in future promised benefits in the package, like price indexing. Just a month after the Social Security reform debate began in earnest last January, Graham came out supporting a tax increase, sharply raising the maximum taxable income for Social Security. Indeed, this is exactly what is already happening. Senator Lindsey Graham’s public comments show precisely this, as they reflect what he has heard from Democrats. Graham started out falling for the idea that the way to get Democratic support for personal accounts was to include cuts in future promised benefits in the package, like price indexing. Just a month after the Social Security reform debate began in earnest last January, Graham came out supporting a tax increase, sharply raising the maximum taxable income for Social Security.

About a month after that, Graham started saying the personal accounts were a “sideshow” and we should drop them and focus on achieving full solvency for Social Security with a package of tax increases and benefit cuts.

Small Accounts Mandate Price Indexing

Price indexing schemes are advanced by those who support only a small personal account option (allowing workers to shift to the account only about 2-3 percentage points of the total 12.4 percent payroll tax). Unlike large accounts, small accounts are not large enough to eliminate the long-term deficits of Social Security. So proponents of small accounts need to add the large future benefit reductions of price indexing to cobble together a package that can eliminate the long-term deficits of Social Security.

Problems with the Price Indexing Approach

Advocates of this approach argue that the small personal accounts earning market returns can make up for the future benefit reductions of price indexing, leaving workers overall with about the same benefits as promised by Social Security today.

But small personal account options of only 2 to 3 percentage points of the payroll tax probably cannot make up for the future benefit losses produced by full or progressive price indexing for all workers. The 3 percent accounts limited to $1,000 in contributions each year under Option 2 proposed by the President’s 2001 Social Security Reform Commission would not make up for the effects of price indexing for all workers at market rates of return on the accounts. The same appears to be true for the 2 percent accounts plus progressive price indexing proposed by Robert Pozen.

Remember, under these personal account options, workers who exercise them would give up additional benefits to be replaced by the accounts in addition to what they would lose under progressive price indexing. Much bigger accounts are needed to make up for all of these benefit changes.

Moreover, the current Social Security system already offers workers a bad deal with low returns and inadequate benefits. Achieving the current level of benefits with the same tax payments as today still leaves workers with this same net bad deal. In other words, the price indexing plus small accounts package simply adds additional risk while not addressing the problem of the poor returns and inadequate benefits under the current system. Indeed, with the transition financing needed for the small personal accounts, workers may end up paying more into the system under this reform, but getting no more in benefits, effectively reducing the rate of return even more.

Personal account reform was supposed to give workers a better deal as well as provide solvency. That held popular appeal. But how appealing is a reform that says if everything works out right with the accounts, you will get the same benefits as promised today? Moreover, if it is not clear that even this will be true for all workers, then everyone will wonder if they will be among the losers, eroding grassroots enthusiasm for the reform.

In addition, the Administration has not supported any kind of benefit guarantee for the personal accounts. Without a safety net guaranteeing current benefits, sub-par investment performance with the small accounts would leave workers with fewer benefits than promised under current law. If the new system cannot even assure people that they would get the current inadequate level of benefits, that too will dissipate any grassroots enthusiasm for the reform.

Another problem is that the personal accounts are supposed to be a voluntary choice. Workers are supposed to be free to stay with the current system and skip the personal accounts if they so desire. But with the price indexing in the package, workers who choose to stay in the current system will have their future benefits eviscerated as described above. This will not be seen by the public as a viable free choice, and personal account advocates will consequently lose the chance to make the argument that they are only offering a choice and workers are free to forego the personal accounts if they desire.

Indeed, Democrats and liberals will focus on what the price-indexing component of the plan would do to the current system, and force Republicans and reform advocates to respond. They will deride the personal account component as “too risky.” With much of the public not sure whether they really do want to exercise the personal account option, this approach will be highly effective, all the more so if the public cannot be assured that even with the accounts they will get at least the benefits promised under current law.

Democratic and liberal opponents of personal accounts, in fact, have already long argued that personal accounts would require massive cuts in future promised benefits. Democratic and liberal opponents of personal accounts, in fact, have already long argued that personal accounts would require massive cuts in future promised benefits. Reform advocates who say price indexing is essential to personal account reforms are effectively admitting that this devastating argument is correct. Democratic and liberal ads, and Democrat leaders on the Hill, are already saying that the President’s personal account plan would require 40 percent cuts in benefits, which is based on the price indexing component. With the price indexing in the plan, Republicans and reform advocates would not be able to deny this charge. It certainly would be true for those who exercise the supposed option to stay in the current system. A response of, “Well, yes, but if you do this, and if everything happens as we hope, then you won’t get cuts and will get roughly what is promised under current law,” will lose too many voters in the confusion, and look too uncertain to most who can follow all that. In other words, it is transparently a political loser.

Finally, combining price indexing with small personal accounts is not working to gain Democratic support in Congress, let alone Republican support. Rather, Democrats are responding exactly as previously suggested. They are insisting that the long-term deficit cannot be addressed on the benefit side alone and any reform plan has to include tax increases as well. They are also insisting that in any event they will not support real personal accounts that substitute for part of the current system. All they will support is add-on accounts that do not provide the great gains that are offered by real accounts. Because Republicans would not dare to try to vote through price-indexing cuts in future promised benefits on a partisan basis without Democratic cover, going down this road is leading us into a tax increase and no real accounts.

Mixing the political negatives of price indexing into the reform effort has already caused a loss of focus on the enormous political positives of personal accounts. It has transformed the debate into an argument over how to balance the Social Security budget with some combination of tax increases and benefit cuts, rather than how to achieve prosperity for workers, freedom of choice, and personal ownership and control through personal accounts. Reforming Social Security with a personal account option was already controversial enough. It can’t bear the political baggage of massive cuts in future promised benefits, and tax increases as well.

Large Personal Accounts Solve the Problem

A wiser course for reformers would be to avoid any benefit cuts or tax increases in the reform plan, and propose instead large personal accounts of just over 6 percentage points, or roughly the employee share of the payroll tax. This would provide workers with much better benefits than the current system promises, let alone what it can pay. So the “bad deal” problem—the problem of low returns and inadequate benefits of the current system—would be eliminated. And, as discussed below, these large accounts would also restore permanent solvency to Social Security.

This approach would keep the focus on the positives of personal accounts. We know reformers would win the issue framed this way, because they have done so over and over in numerous election campaigns over the last three election cycles. The many candidates who have won on personal accounts in these elections focused on the personal accounts alone. They never said anything about tax increases or benefit cuts. In every one of these elections, the pro-personal accounts candidate won.

Price indexing was advanced in the first place to achieve full solvency in Social Security with just small personal accounts. Price indexing is really the alternative to large personal accounts. This is why those who favor large personal accounts have been foolish to embrace price indexing as part of the reform plan. Indeed, as shown below, adding price indexing to a plan for large personal accounts would have little effect because by the time price indexing would start to build up to a significant impact, the large personal accounts would have already shifted so much in benefit obligations to the accounts that price indexing could no longer have much effect.

Better to argue on the Hill that the large personal accounts allow Social Security to be reformed and its problems solved without tax increases or benefit cuts. That is the most politically powerful argument for large personal accounts on the Hill. Those who have tried to embrace both price indexing and large personal accounts have thrown this argument away. They are well on their way instead to achieving a tax increase with no real accounts.

The mistake the Administration has made on Social Security is to send the President out to argue that (1) Social Security has a big problem and (2) personal accounts won’t solve the problem. This is not the way to sell personal accounts. That is why the more the President talks about personal accounts, the lower they go in the polls. With this message, he is not advancing personal accounts.

Large Personal Accounts are the Only Real Solution

Worst of all, it is absolutely untrue that personal accounts won’t solve the problem. In fact, only large accounts can solve all of Social Security’s problems. Tax increases and benefit cuts can’t solve the problem. Rather, they would make the problem worse because they would make Social Security an even worse deal, with lower returns and even less adequate benefits. Personal accounts would provide workers a better deal, and solve the solvency problem.

As workers exercise the personal accounts, the responsibility for paying a proportionate share of their future promised benefits shifts from the old Social Security framework to the accounts. With large accounts allowing workers to shift just over 6 percentage points of the payroll tax to the accounts, so much of the future benefit obligations of Social Security are shifted to the accounts through this process that Social Security is left in permanent solvency.

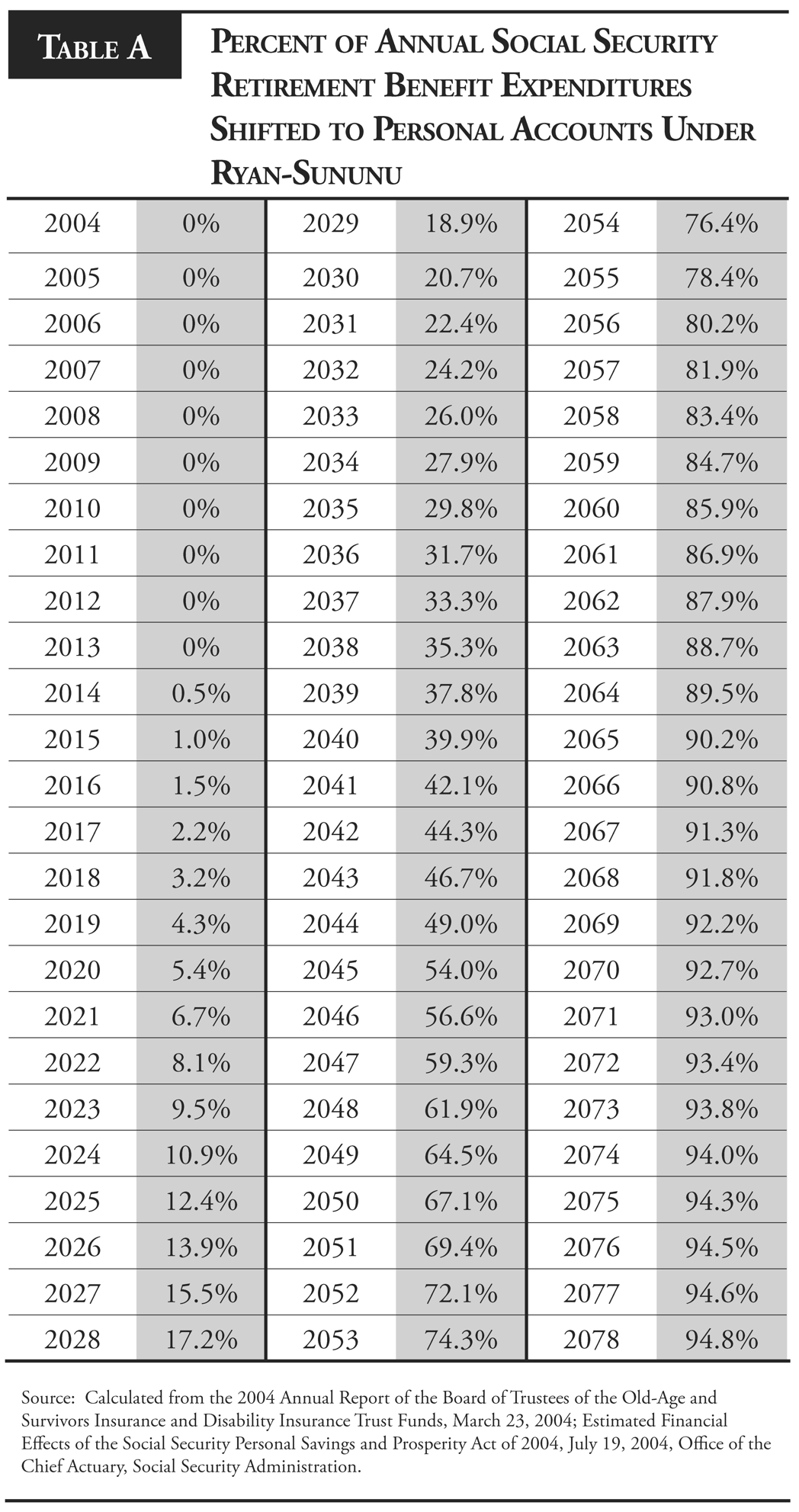

For example, under the legislation introduced by Rep. Paul Ryan (R-WI) and Sen. John Sununu (R-NH), workers are allowed to shift to the accounts on average 6.4 percentage points of the 12.4 percent payroll tax. Table A shows the effect this option would have in reducing future projected expenditures under Social Security for retirement benefits (again, with better benefits paid through the accounts). The table shows that the program’s currently projected expenditures would be reduced by 40 percent in 2040, 67 percent in 2050, 80 percent in 2056, and 95 percent by the end of the projection period. With almost half the payroll tax still going into Social Security, this puts the program into permanent surplus, which is why the Ryan-Sununu bill includes a payroll tax cut trigger that would eventually reduce the payroll tax when the surpluses reach a certain level.

In addition, the large personal accounts do not need to be adopted all at once to achieve these results. The large accounts can be phased in through two or more steps. That will delay the achievement of full solvency depending on how long the phase-in is. But the full solvency would still be achieved.

Therefore, members of Congress and of the Administration, including the President, are completely wrong when they say the personal accounts cannot achieve solvency in Social Security by themselves. Indeed, the Chief Actuary of Social Security has officially scored three other plans as eliminating Social Security’s financing problems and assuring payment of all benefit promises through the effects of personal accounts alone, without any tax increases or benefit cuts.

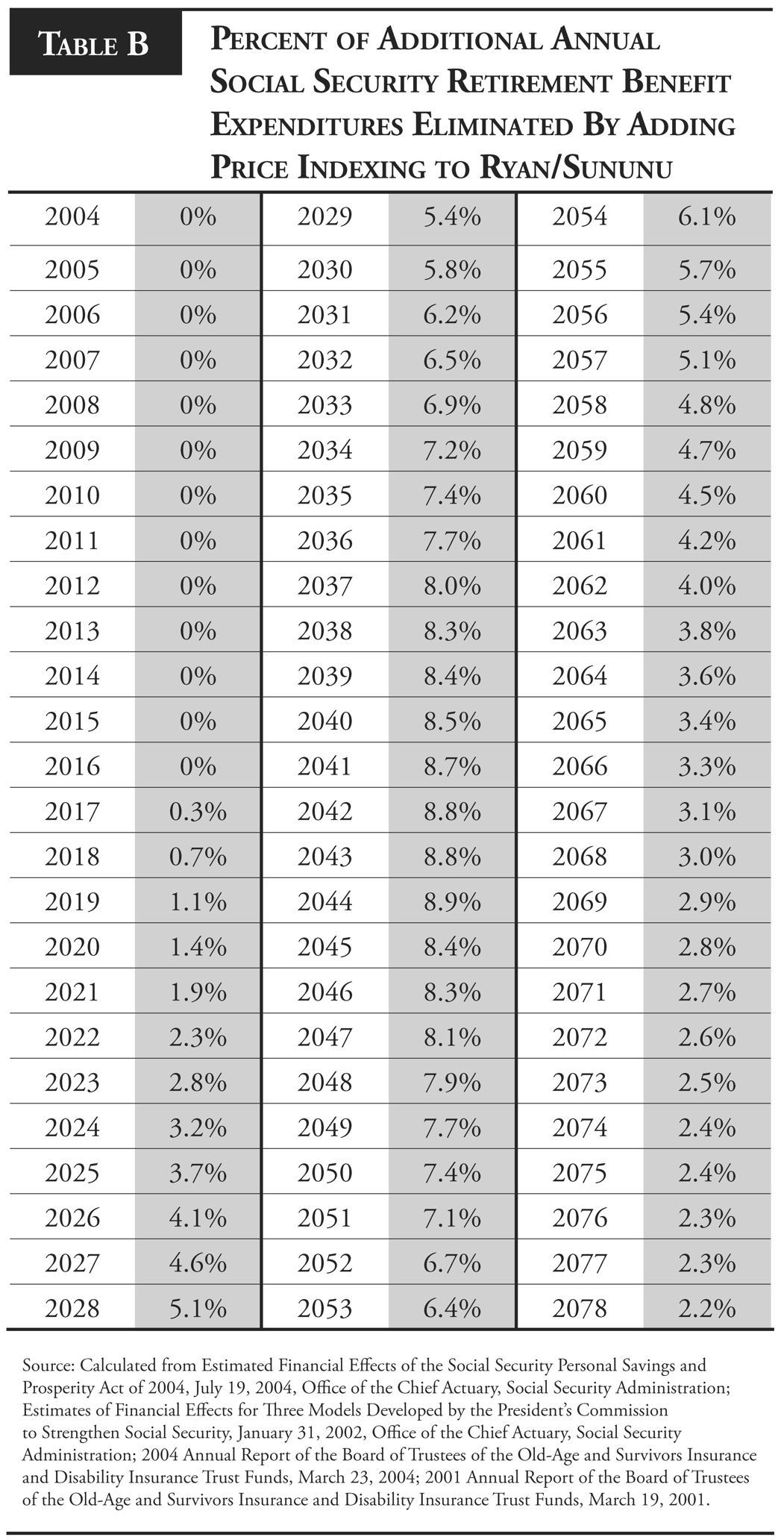

Table B shows the negligible effect price indexing would have if we tried to add it to a reform plan with large personal accounts like Ryan-Sununu. This is the effect of full price indexing for everyone under age 55. Progressive price indexing would have a substantially smaller effect. By 2030, the price indexing would only reduce projected Social Security expenditures by another 5.8 percent. The effect of price indexing peaks in 2044 at 8.9 percent, when the Ryan-Sununu personal accounts alone would be reducing projected Social Security retirement expenditures by about 50 percent. By the end of the projection period, price indexing is only reducing projected expenditures by an extra 2 percent, while the Ryan-Sununu accounts would have reduced those expenditures by 95 percent. This effect is so small because the effects of price indexing accumulate slowly at the start, and by the time the effect would start building up to a major amount, the large personal accounts would have shifted so much of Social Security retirement expenditures to the accounts that there is not much left for price indexing to cut.

The Administration and Republicans in Congress should just propose the largest personal account they think can be reasonably handled now. The proposal would include no cuts in future promised Social Security benefits and no tax increases. The policy would then be that we will start here and eventually solve all the problems of Social Security by expanding the accounts to the full Ryan-Sununu level.

Conclusion

Upon analysis, it becomes clear that price indexing is politically indefensible. Moreover, it cannot solve the biggest problems of the program, as it would make Social Security an even worse deal with even lower returns. Politically, it is likely to lead to a tax increase as well, and no real accounts, or just kill reform altogether.

With a large personal account option as in the Ryan-Sununu bill, price indexing is completely unnecessary. Such large accounts provide workers a much better deal than the current system, and restore Social Security to permanent solvency, eliminating all future deficits in the program. The Administration and Congress should consequently focus on reform involving large personal accounts alone, without tax increases or benefit cuts, as in the Ryan-Sununu bill, even if it has to be phased in over time.

Endnote

- Peter Ferrara and Michael Tanner, A New Deal for Social Security (Wash. DC: Cato Institute, 1998), Chapter 4. See also William W. Beach and Gareth G. Davis, Social Security’s Rate of Return, A Report of the Heritage Center for Data Analysis, Washington, DC, No. CDA98-01, January 15, 1998.

About the Authors

Tom Giovanetti is the President of the Institute for Policy Innovation.

Peter Ferrara is a Senior Research Fellow with the Institute for Policy Innovation and Director of the Social Security Project for the Free Enterprise Fund.

About the IPI Center for Economic Growth

Few public policy issues are as critical as sustained economic growth. Through the IPI Center for Economic Growth, the Institute for Policy Innovation pursues policy changes designed to increase levels of stable, predictable economic growth. The Center believes that critical lessons were learned during the 20 th Century (particularly during the 1980s and 1990s) about how private property, government regulation, tax policy and monetary policy contribute to or undermine economic growth, and seeks to apply those lessons to 21 st Century policy issues. The Center advocates protecting private property, deregulation, competition, innovation, entrepreneurship, stable currency, and lower tax rates as means to achieving sustained high levels of economic growth, and denies that there is any public policy downside to high levels of economic growth.

About the Institute for Policy Innovation

The Institute for Policy Innovation (IPI) is a nonprofit, non-partisan educational organization founded in 1987. IPI’s purposes are to conduct research, aid development, and widely promote innovative and nonpartisan solutions to today’s public policy problems. IPI is a public foundation, and is supported wholly by contributions from individuals, businesses, and other non-profit foundations. IPI neither solicits nor accepts contributions from any government agency.

IPI’s focus is on developing new approaches to governing that harness the strengths of individual choice, limited government, and free markets. IPI emphasizes getting its studies into the hands of the press and policy makers so that the ideas they contain can be applied to the challenges facing us today.