One of the most pressing issues currently facing the Internet is whether and how to tax it. According to one estimate, 64.2 million adult Americans go online each month.1 Millions of Americans access the Internet daily for information, to make purchases and even gamble. As a result, businesses across the country have been looking for ways to respond to or incorporate the Internet into their business plans. For example, information is so widespread on the Internet today that Encyclopedia Brittanica recently decided to put its volumes of information on the Internet for free, thereby largely eliminating its business model. Should access to that information on the Internet be taxed?

Another growing issue is Internet sales.

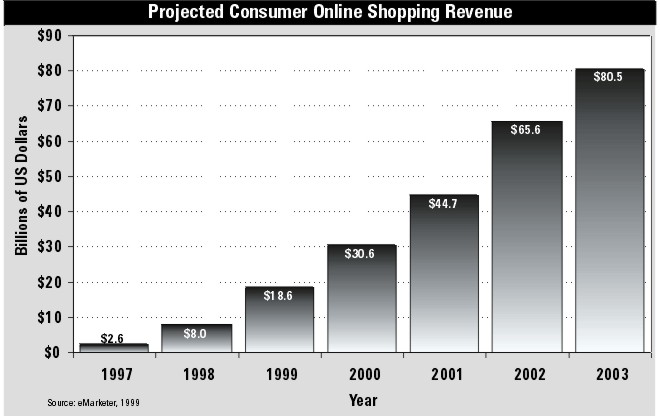

- Although business-to-consumer sales are currently only about 2 percent of the $2.7 trillion retail industry, that figure is expected to grow to $108 billion, or 6 percent of retail sales, by 2003.2

- Business-to-business e-commerce is expected to grow to $1.3 trillion by 2003, though only a portion of that amount may be subject to a sales tax.3

Should that commerce be taxed? If so, then how? If not, doesn’t that create an unfair advantage for businesses that sell on the Internet? According to a coalition of government-oriented associations such as the National Governors’ Association and the U.S. Conference of Mayors, not taxing e-commerce would cost state and local governments between $9 billion and $11 billion in lost revenue by 2004.4

While deciding not to tax the Internet raises several problems, so does imposing a tax. How will businesses ensure the privacy of purchasers? Would government keep a record of those purchases? Would an Internet sales tax slow the growth in e-commerce, and would e-tailers flee U.S. shores in order to avoid the tax?

Before Congress or state legislatures push forward on taxing the Internet, policymakers need to take a close look at the issues and the impact taxes would have on the new e.conomy.

Growth of the New e.conomy

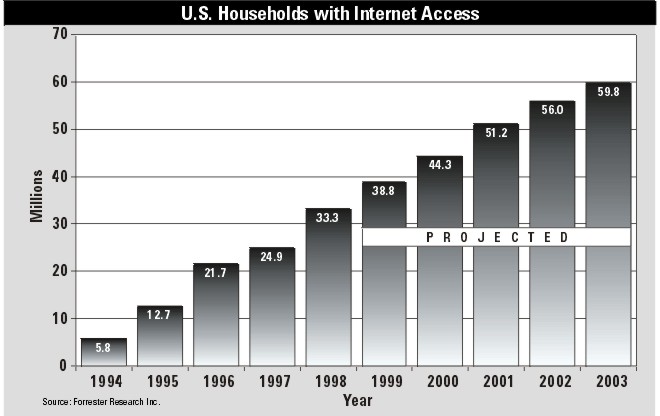

E-commerce is growing at a phenomenal rate. According to Forrester Research: 5

- 17 million households shopped online by the end of 1999, spending an average of $1,167 per household.

- By 2004, that number is expected to grow to 49 million households spending an average of $3,738 each.

However, business-to-consumer sales are only part of the economic activity generated by the Internet. Companies hire consultants to help them with their web sites, pay to get their Internet service and many other expenses. According to the University of Texas’ Center for Research in Electronic Commerce, the Internet economy—i.e., commerce directly and indirectly a result of the Internet—created $301.4 billion in 1998 and was responsible for 1.2 million jobs nationwide. About a third of that amount, $102 billion, was a direct result of Internet commerce.7

The growth in Internet activity and sales has politicians and bureaucrats at the federal, state and local levels considering several new ways to tax e-commerce. However, states’ attempts to tax the Internet have met with resistance, most notably from Congress. Before states plunge into creating new Internet tax schemes, they should consider their options and whether imposing new taxes, enhancing collection efforts under their current taxing authority, or leaving the Internet tax free is the best economic and tax policy to adopt.

Can States Tax the Internet?

Some states already tax the Internet. For example, several states have imposed a tax on the cost of using an Internet service provider (ISP) such as America Online. But many don’t want to stop there.

Federal, state and local governments have the constitutional or statutory authority to collect taxes—such as sales and use taxes and taxes on business income—when people and businesses fall within the governmental body’s jurisdiction. That includes traditional retail sales, catalogue sales and sales made over the Internet.

The rationale behind the current taxing system is that a customer living within the state’s boundaries benefits from the highways, police and other public services funded by the sales tax. Therefore, the customer has an obligation to pay the tax. People living outside the state’s boundaries are unlikely to benefit from that state’s public services and so should not be obligated to pay the tax.

However, a number of caveats exist. If a customer buys a product subject to a sales tax in a retail store, the vendor collects the tax at the point of sale and passes it on to the state. If retail vendors take an order over the phone, they are supposed to charge that sales tax if the purchaser lives within the same state. If the customer lives in a different state, vendors do not collect a sales tax. However, unbeknown to most people, the customer may still be obligated to pay a “use” tax to his home state. But the fact is that almost no one does that; for that matter, almost no one knows they’re supposed to.

Catalogue Sales

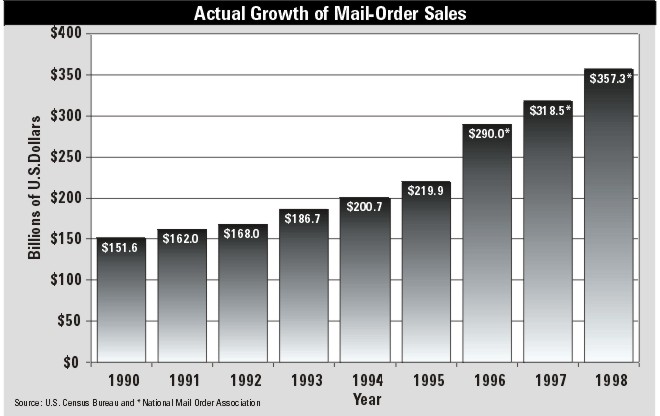

Issues surrounding taxing the Internet are not new; they are the same ones that have plagued catalogue sales for years. This year, about 15 billion catalogues will be delivered to people’s homes.8 That works out to about 50 catalogues for every American. And consumers will spend an estimated $57 billion buying those products. Long before the Internet became the focus of discussion, interstate catalogue sales raised the same questions about sales taxes.

States and local communities see their inability to tax interstate sales as a loophole that costs them revenue, and they have gone to the courts in order to force companies to collect the tax for them.

In Quill Corp. v. North Dakota , the U.S. Supreme Court ruled in 1992 that the Commerce Clause barred the states from requiring an out-of-state mail-order company to collect taxes on sales made to customers inside the state unless the company had a substantial presence (referred to as “nexus”) within the state. Since Quill had no outlets or sales representatives or other significant presence within the state of North Dakota, it did not have to collect the tax.9

Thus, while states have the right to collect taxes, that authority stops at their borders. However, the states are currently doing their best to change that fact. A number of groups including the National Governors’ Association, National League of Cities, National Association of Counties, U.S. Conference of Mayors, National Conference of State Legislators, Council of State Governments and the International City/Council Management Association are backing a proposal that they claim would simplify state sales tax assessments and collections, making it easier to collect taxes on interstate mail-order or online purchases. If successful, the net effect of their proposal would be to bypass Quill.

As Figures 2 and 3 show, Internet sales are still relatively small compared to catalogue sales, but tax advocates see the potential for e-commerce growth as a major source of lost revenue in the future. As a result, states are considering their options for new or more aggressive tax-gathering efforts.

Internet Tax Options

Internet tax proponents have suggested a number of ways to raise tax money from the Internet. Some would be much easier to monitor and collect than others. Some would have a more derogatory economic effect than others. What tax ideas are on the table?

Sales Taxes

The primary focus of attention for Internet tax proponents is an e-commerce sales tax that would require vendors to collect a sales tax when someone purchases something online. Whether some items such as food or prescription drugs would be excluded, as many states currently exclude them under the states’ sales taxes, is still up for debate. In addition, it isn’t clear whether services such as legal, medical or financial services sold over the Internet would or should be taxed.

Sales tax proponents are currently considering two basic approaches. One approach—a version of which has been proposed by Sen. Ernest Hollings (D-S.C.)—would impose a uniform Internet sales tax nationwide so that all vendors operating within the U.S. would have to collect the tax on all qualified sales.

There are several advantages to this type of approach. Currently, there are some 7,548 taxing jurisdictions within the United States.10 Knowing which tax level to apply to whom and on which purchases—since states can vary on what items they tax—could be difficult. In addition, there is a growing interest among states, especially in light of so many states having budget surpluses, in exempting for limited periods of time certain items that would normally be taxed—that is, vendors do not collect sales taxes either on certain days or on certain items. For example, the state of Texas recently implemented legislation that bans sales taxes on certain back-to-school items on designated days in August.

A uniform federal sales tax would solve the problem of multiple jurisdictions and the limitations placed on states by the Commerce Clause. Congress would have to set the level of the tax and determine what would and would not be taxed. The sales tax money collected by the businesses could either be sent to Washington, which would redistribute it based on some formula, or could be sent directly to the state or other taxing authority in which the vendor resided.

The downside of this approach is that it would create a huge new opening for the federal government to oversee and regulate taxes at the state level, imposing a real threat to federalism. The states should think very carefully about giving up that much power and control.

The other and more popular approach would require online vendors to collect sales taxes based on the residence of the purchaser, not the vendor.

This approach has the advantage of simply using the existing tax structures within the states and local communities. Congress would not be creating a new tax. However, it would require some type of waiver in the Commerce Clause which currently prohibits requiring such collections, or it would require some type of mutual agreement among the states, similar to the one the NGA is proposing, that did not run afoul of Article I, Section 10 of the Constitution which says “No state shall, without the consent of Congress,…enter into any agreement or compact with another State . . . .”

One problem is that it would create an administrative nightmare knowing how much to tax whom. Proponents of the tax argue that the software that would calculate the correct tax based upon a purchaser’s residence is already available and can be purchased for as little as $1,000.11 However, even if software can immediately determine which tax is appropriate for each sale, actually getting the money to the taxing jurisdictions would be difficult. Can you imagine, say, 20 million vendors trying to transfer money to 7,500 different taxing jurisdictions?

Perhaps more importantly is the privacy concern—the sales tax would require some method of collecting the information about the purchaser and what he purchased. If a purchaser buys something in a retail store, there is little need for the vendor to get personal information such as where the customer lives, unless the customer is having the product shipped to his home. And even that is largely non-problematic, since outside entities don’t have access to that information. As a result, there is little possibility of someone examining people’s purchasing habits—especially by the government—or for that information to be used against the purchaser at some time in the future. Although credit cards leave a trail, that information can be difficult to access without going through the proper channels.

Not so with online purchases subject to a sales tax. Not only will vendors need an address in order to know where to ship the item, they need an address to know which of the 7,500 taxing jurisdictions the customer lives in so they know how much tax to charge. Were vendors able to send the appropriate government bodies a check for the tax as discussed above, that might create an administrative headache, but not a real privacy problem. But high-sales companies could end up writing tax reimbursement checks to all 7,500 jurisdictions. As a result, proponents of this approach are looking for a third party that would receive the tax money from vendors who would in turn distribute it to the taxing jurisdictions. Databases created by such third parties are a real source of privacy concerns—someone, including the government, will know who you are and what you buy.

Of course, if all states decided to tax Internet sales at the same rate, many of the accounting problems would be solved.

One seldom-discussed solution to the problem of the multiple-taxing authorities would be to require online vendors to impose the sales tax appropriate for its place of business, rather than the residence of the purchaser. That is, an online vendor located or incorporated in Texas would charge Texas’ sales tax on all sales, regardless of the location of the buyer. And each vendor would turn those taxes over to its respective state. This is, in effect, the way the sales tax works when someone from one state purchases something while in another state. In this case the nexus applies to the seller rather than the buyer, just as when a customer travels to another state and purchases something from a retail outlet (as discussed by Dean Andal below). If Smith purchases something while in another state, the vendor charges Smith the state’s sales tax. The vendor doesn’t ask or care whether Smith is from another state or not.

This method of taxing Internet sales might also require statutory changes to deal with the Commerce Clause, but at least it simplifies the method of taxation and eliminates the concern that the government would be gathering information on customers and their purchases.

Use Taxes

A use tax applies to the location where a purchaser “uses” something he purchased, and is generally considered the flip side of the retail sales tax. If a resident of one state purchases something in another state, that doesn’t necessarily mean he can avoid paying a tax on the item purchased. The state of residence can impose a use tax on the item.

Case Study #1:

Texas State Land Commissioner David Dewhurst was recently hit unexpectedly with a tax bill from the Texas comptroller’s office. According to a news account, Dewhurst could have to pay up to $82,500 in taxes for purchasing between $750,000 and $1.3 million in furniture, art and other items out of state.12

The comptroller’s office learned about Dewhurst and 300 other Texans from the U.S. Customs Office. They now have to pay an 8.25 percent excise tax on the value of the purchases. Dewhurst was caught unaware, according to the story, but that is not surprising since almost no one knows about the law. And had the comptrollers office not received notification from the Customs Office, the tax never would have been levied.

Case Study #2:

The state of California recently sent 3,200 residents a tax bill for cigarettes purchased out of state. According to the Orange County Register, thousands of Californians are buying cigarettes online because they can get them cheaper and pay no state tax.13 However, the out-of-state seller is required by federal law to report the name and address of the buyer to the buyer’s state of residence.

Use taxes can be very difficult to implement and monitor. As Dean Andal, vice president of the California State Board of Equalization and a member of the Advisory Commission on Electric Commerce, says:

Unlike the bricks and mortar business that state and local governments so often argue are being discriminated against, the out-of-state retailer is asked to do that which the in-state retailer is not: determine the place of use for each of its customers. For example, the brick and mortar retailer doesn’t ask if I’m taking my purchase and going back to my home which is in a different taxing jurisdiction. They don’t care. The sales tax treats the place of purchase as the place of consumption. However, if the same transaction occurred online, via the company’s web page, different standards would apply. If the store is in my home state, most likely the sales tax would once again apply but the seller would first have to determine the destination of the sale. If the seller was in a different state, the use tax applies and the seller would have to identify the destination of the sale and collect and remit based on the rules and rates for that local jurisdiction assuming the company has nexus (reliance on zip codes is not legally sufficient as many zip codes cross taxing jurisdictions). In the purely digital world, where both the consumption of the agreement and the exchange of the product or service occurs online, location is not just irrelevant; it can be impossible to determine. The use tax is not a surrogate consumption tax as some would suggest. It was a device conceived to protect in-state merchants.14

Access Taxes

The Internet Tax Freedom Act prohibits states from imposing new taxes on the Internet, but taxes that were already in effect were permitted to remain. One type of tax that several states had turned to was the “access tax,” which taxes access to the Internet by imposing a tax on the fees charged by Internet service providers such as America Online.

For example, according to the National Conference of State Legislatures, by March 1998, 10 states, Washington D.C. and several local governments were taxing Internet access.15 However, several of those states have since eliminated or suspended the access tax.

Utah Gov. Michael Leavitt has devised a variation of the access tax. As the demand for high-speed Internet access explodes, cable companies are expanding to meet that demand. In 1999, the state’s Rights of Way Task Force recommended a one-time, $500-per-mile charge when cable firms lay cable along the right-of-way strips next to interstate highways.16 That tax would eventually be passed on to cable users, thus indirectly taxing high-speed Internet access.

While access taxes are fair, in that they tax everyone at the same rate, they have fallen out of favor with many people because they, in effect, impose a tax on information. As Table 2 shows, the vast majority of people who use the Internet do so for information.

As a result, there seems to be a growing consensus that access taxes, while fair, are not a good policy option for raising revenue.

Delivery Taxes

Most of the products people buy online have to be delivered to their home or place of business. As a result, some have proposed requiring delivery services such as railroad, airline or trucking firms to collect a tax for their services, thereby indirectly taxing Internet sales. One way to achieve this is to impose the delivery tax at the time of purchase, since collecting it at the door would be very difficult and slow down delivery drivers.

Miscellaneous Taxes

There are a number of other ways that proponents are envisioning taxing the Internet. For example, states or cities might impose a tax when a home installs a second phone line. Although such a line could be used for conversation, the operating assumption behind this proposal is that the new line would be used for computer access to the Internet. High-speed access lines might also be targeted as good subjects for a tax.

Internet Tax Proposals

The growing demand for access to and use of the Internet has spawned a number of schemes meant to increase tax revenues. In some cases, those schemes have become formal proposals or legislative language.

Sen. Hollings’ Federal Internet Sales Tax

Last year, Sen. Ernest Hollings (D-S.C.) introduced his “Sales Tax Safety Net and Teacher Funding Act” (S. 1433), which would impose a 5 percent sales tax on all retail sales over the Internet and through mail order. Money collected from the tax would be sent to the U.S. Treasury and deposited in the “Sales Tax Safety Net Trust Fund.” That money would ultimately be distributed to the states based on a formula and used primarily to increase teachers’ salaries. If salaries were already high in the state, the funds could go for other educational purposes.

Hollings’ proposal in its current form is visible and taxes all sales at the same rate. It has minimal privacy problems because the buyer’s residence is irrelevant; the customer pays the same tax irrespective of his residence or the vendor’s location. As a result, little or no information is needed about the buyer, except for shipping purposes.

However, the Hollings bill would represent a new and unprecedented federal incursion into state activities. Apparently, the states would be unable to collect any sales or use taxes on merchandise bought online or through mail order. Thus it is unlikely that a state could collect use taxes from one of its citizens who had bought cigarettes over the Internet in order to avoid the state’s taxes. While states don’t collect a lot of money through use taxes, the Hollings bill may undermine any future attempts to do so, costing the states revenue.

But wouldn’t those losses be more than made up when the states receive their share of the tax? Probably, but that money comes with strings attached. It must be used on education, and so would not be available for general revenues.

National Governors’ Association

The National Governors’ Association (NGA) has gone far beyond the issue of whether or how to tax Internet access and sales. It envisions restructuring the states’ sales tax systems nationwide.17 By so doing, it hopes to make collecting taxes on mail-order and Internet sales much easier. According to the NGA, “The proposal’s key tenet is to achieve significant simplification of sales tax systems to match the rapid evolution of the information economy and global trade.”18 Some of the main components of the plan are:

- Eliminate the burden placed on firms to collect state and local sales taxes;

- Keep the current definition of nexus;

- Enact this system at the state level, without federal involvement;

- Phase in the system on a voluntary basis;

- Eliminate monitoring, record keeping and compliance costs for businesses.

Stated briefly, the plan would simplify the way states collect sales and use taxes by making them more uniform. States would contract with “trusted third parties” (TTPs), independent organizations created to process sales taxes, which would monitor their client organizations’ sales, collect the taxes paid by purchasers and distribute the appropriate amount to the various municipalities. In other words, the TTP is supposed to become a middleman, handling all of the tax collections and distributions, making life easy for both retailers and state governments.19

The key to the NGA proposal is software. The NGA believes that retailers, states and the TTPs will have access to software that will analyze the consumer’s address, compute the appropriate tax to charge and inform the TTP, which would bill the business for the tax. Software would do it all— including ensuring consumer privacy. Under the NGA proposal, the software would compute the tax based on the residence of the purchaser but would not transfer that information to the TTP. Between simplifying the states’ sales tax systems and using the software to process the information, the NGA envisions a whole new era in tax collection. Indeed, the NGA calls its proposal a “ Streamlined Sales Tax System for the 21st Century.”

One troubling aspect of the NGA proposal arises when the question is asked, What if a state doesn’t want to adopt the NGA’s “voluntary” proposal. The NGA writes, “Ultimately the voluntary system will be extended to all states and localities as well as for all remote sellers, ending the inequity of the current system. In order to collect sales and use taxes, states will have to conform to the uniform, nationwide system. States that do not adopt this approach and mechanism by a fixed date will be denied the ability to collect taxes on remote sales until they adopt the uniform system.”20 So much for a voluntary system.

Another problem appears to plague the NGA’s proposal—it’s anti-competitive. Historically, the states have competed against each other in a variety of ways. For example, some state legislatures try to create a business-friendly climate by keeping corporate taxes low, minimizing regulations or offering tax breaks if certain types of businesses move to the state (or city, in some cases). That competition is healthy and spurs economic development. Four states have no sales tax and seven have no state income tax. That’s the type of diversity that comes with real federalism.

While the NGA’s desire to simplify the sales tax system is laudable, there may be an underlying motive to eliminate competition. The NGA knows there is still a question about how to determine a company’s nexus if its corporate headquarters is in one state, the online operations in another and the server in a third. Uniform sales taxes, if that is what the proposal would produce, could be construed as price fixing. As a result, there would be no incentive for a company to look to another state for a better deal. In other words, simplification could just be collusion with a friendly face.

Advisory Commission

The Advisory Commission on Electronic Commerce (ACEC) is a 19-member, congressionally appointed committee charged with undertaking “A thorough study of federal, state and local, and international taxation and tariff treatment of transactions using the Internet and Internet access and other comparable intrastate, interstate and international sales activities.” 21

The commission has held several meetings around the country and has taken testimony and comments from interested parties. Because Congress is looking to the commission for recommendations, its findings will likely have a significant impact on the Internet tax debate. It is scheduled to release its report and recommendations to Congress in April 2000. However, a draft report has been circulated that provides some insight into what the commission will be proposing, though so far most of the recommendations are mostly platitudes without much specific guidance. For example, the commission supports policies that:22

· Establish an environment that continues to foster innovation and technological advancement in the development of the Internet and electronic commerce;

· Are respectful of the sovereignty of state and local jurisdictions;

· Simplify current sales and use tax systems;

· Create a system that is efficient and fair and can remain viable in the 21st century.

Interestingly, the draft specifically states that “At this time, it does not appear that there is any compelling reason to impose taxes exclusively targeted at electronic commerce,” and that “Governments should keep tax burdens on American consumers and businesses as low as possible.”

Arguments for and Against Taxing the Internet

There are two primary arguments used to support new or expanded Internet taxation: fairness and lost state revenue. Although tax proponents stress both arguments, it is clear each argument has a constituency. State, county and local elected officials are most concerned about the loss of revenue if untaxed Internet sales continue to grow. Retailers, who have had to deal with sales taxes for years, turn more to the fairness argument. Both arguments have some merit, but is it enough to justify taxing Internet sales? Or are there other solutions that might satisfy the fairness argument without taxing e-commerce?

Would States Lose Revenue?

When consumers choose to buy a product or service online rather than in a retail outlet, in most cases they avoid any applicable sales taxes, which means a state loses that revenue. A retailer selling a $1,000 computer might have to charge a purchaser, say, $80 in sales tax, while that same customer might be able to buy the computer tax free over the Internet—thus saving the customer $80, less shipping costs, and costing the state $80 in revenue.

Tax proponents contend that over time and as e-commerce grows, states will lose significant amounts of revenue, threatening essential services that the public has come to want and expect. For example:

· Economist Henry J. Aaron of the Brookings Institution has written, “ Whatever its strengths, however, e-commerce hasn’t eliminated the need for schools, fire departments, police forces, parks, libraries, health care and other government services and for the revenue to maintain them.” The implication, of course, is that without an Internet sales tax, these services would be threatened.23

· Joseph Brooks, a councilman for the city of Richmond, Virginia, speaking on behalf of the National League of Cities, National Association of Counties, U.S. Conference of Mayors, National Conference of State Legislators, National Governors’ Association, Council of State Governments and International City/Council Management Association, has said: “We believe the lost revenue from tax-free online shopping will be significant—between $9 and $11 billion by 2004. If our sales taxes shrink dramatically or even disappear because of tax-free online shopping, we will be forced to raise taxes in other areas to provide essential public services like police and fire protection and public education.”24

· “None of us wants to pay taxes,” Dallas Mayor Ron Kirk, a member of the Advisory Commission, has said with regard to taxing the Internet, “but you certainly don’t want the phone to go unanswered when you have a fire, or when you have a need for police.”25

Answering the Lost Revenue Argument

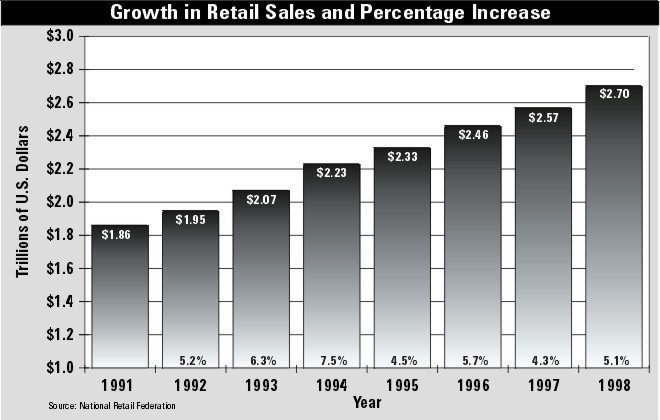

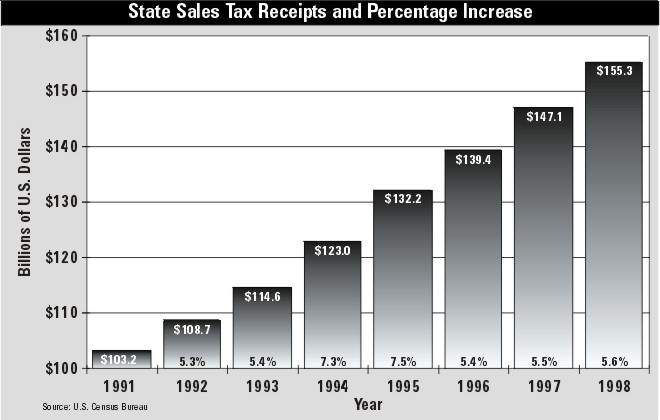

The assumption behind this argument is that if online sales increase, state revenues will decrease. That is not necessarily true. As Figure 4 and 5 show, both retail sales and state sales tax receipts have continued to grow during the decade of the 1990s, even with the growth of Internet sales.

How can sales tax revenues continue to grow while more people buy online? Several reasons.

1. First, although people like to point to aggregate online sales, many of these purchases would not be taxed if bought in-state. For example, online pharmaceutical sales have been growing rapidly, but prescription drugs are not generally subject to the sales tax. In addition, many people purchase such items as airline tickets online, which are not typically subject to state sales taxes.

2. States have various ways of collecting at least some of the sales and use taxes for out-of-state mail order and online purchases. As discussed above, California is collecting taxes on out-of-state cigarette purchases. And Texas collected $1 billion in use taxes in the last budget year, according to the state comptroller’s office.26

3. There is an assumption that there is a direct trade-off between an online purchase and a lost retail sale. However, online consumers are just as subject to impulse buying as those shopping retail—perhaps moreso in certain areas such as technology products. They might never have bought the product if they had to get in a car and go to the store. In other words, a retail outlet didn’t necessarily lose the sale because the consumer had no intention of going to a retail store to buy it.

4. Finally, online sales have a “multiplier effect” that spurs sales both online and in retail stores, and thus spurs economic growth. For example, online sales are helping to keep inflation down which generates more economic activity. Economists Ethan S. Harris and Joseph T. Abate of Lehman Brothers found that Internet prices average 13 percent lower than retail stores even with the shipping costs. In addition:27

- Prescription drugs, which would not be subject to sales taxes, averaged 28 percent cheaper online;

- Alcohol and tobacco are 28 percent cheaper, but states have ways to collect those taxes;

- The savings for electronic products was only 4 percent;

- While toys and hardware actually cost more online than in retail stores.

Indeed, people expect to find lower prices online. According to KPMG, 60 percent of online shoppers expect to pay less when they buy something online than if they buy it in a retail store. Only 37 percent expect to pay about the same.28

The price competition created by Internet sales is keeping prices down for both retail and online sales, and that spurs economic growth. Of course, this type of competition might be short-lived, and there is some evidence that online and retail sales prices might be converging.29 But without that competition, prices would be higher and sales would be lower—which would cost the states money.

The Fairness Argument

The other primary argument heard from sales tax proponents is the fairness argument. Requiring brick-and-mortar businesses to collect a sales tax that online retailers don’t have to collect is discriminatory, they say. Brick-and-mortar businesses must charge a price that is effectively between 3 percent and 7 percent more than online businesses—and that doesn’t include local sales taxes. From an economic efficiency standpoint, the increased price is not a result of price gouging or poor efficiency, since it is simply added on to the price of the item. Thus, that price increase gives customers a strong incentive to do their shopping on the Internet—or through mail order—rather than in the stores, and effectively penalizes traditional retailers through no fault of their own.

Answering the Fairness Argument

The fairness argument is the most compelling because it is based on principle, and it is the most difficult to answer because people are divided over what makes a tax “fair.” Is a fair tax one that requires everyone to pay the same rate? If so, then the Hollings proposal discussed above is fair. However, others argue that a tax is only fair if it is based on the ability to pay, so that middle- and upper-income families pay taxes, but not lower-income families.

But the fairness question is not restricted just to those who must pay the tax. A tax or tariff can affect the sales of those who must charge a tax, since a tax or tariff raises the effective price of one product or service relative to another, and is therefore considered discriminatory.

With respect to Internet sales, states and retailers say that imposing a sales tax on retail sales and not e-tail sales discriminates against retail sales and thus violates the principle of fairness. States complain that as a result they are losing revenue from Internet sales, which may ultimately affect the level of services states will be able to provide in the future.

While the argument for fairness is compelling, it loses some of its force when states try to tie it to state revenues, since state sales tax revenues continue to grow and most of the states have budget surpluses. Indeed, as discussed below, many of the states have been cutting taxes or otherwise returning some of their budget surpluses to the taxpayers.

The problem with the fairness argument within the debate over taxing online sales is that it only wants to go one way—increasing taxes—which makes fairness-argument proponents appear to be less than honest. Another way to create the level tax playing field they want would be to lower sales taxes on retailers as some states have already done. But no one, and especially not government officials, appears to be taking that approach as a solution to the Internet tax issue.

If fairness were really the issue, then retailers would be indifferent as to whether state and local governments imposed an equal sales tax rate on e-tailers, eliminated sales taxes on retail stores, or somehow split the difference (i.e., lowering the sales tax rate on retailers while imposing a small sales tax on e-tailers). For example, under the fairness argument, retailers might support eliminating the sales tax and replacing it with a larger corporate income tax, as long as e-tailers were paying the same tax as their retail counterparts. Since businesses simply pass any kind of corporate income tax on to consumers in the form of higher prices—just as consumers pay the sales tax—retailers should be indifferent to the way the tax is collected as long as both retailers and e-tailers pay the same tax.30 But again, no one is making that argument.

As for government officials, although they also make the fairness argument, it is clear that their real concern is revenue—increased revenue. Government officials are not looking at lowering the sales tax on retailers to make things more fair. Nor are they looking at other options, such as going to a larger corporate income tax. They only look at how to add taxes to the Internet and e-commerce.

Duplicity Among Fairness Proponents

If fairness really were the issue, you would expect those who make the argument to be consistent with regard to other businesses. If it is unfair to tax retail sales and not online sales, then fairness proponents should oppose other schemes that give tax breaks to one business and not another, or to one type of business and not another. But that’s not the case. Indeed, some fairness proponents support discriminatory tax breaks.

Case Study: Mayor Ron Kirk.

Dallas Mayor Ron Kirk has been one of the most outspoken of the fairness proponents. Taxing brick-and-mortar sales and not Internet sales would provide a competitive advantage to Internet businesses. Yet, Mayor Kirk has also been a proponent of tax breaks that create a competitive disadvantage. For example:

· In 1998 the Dallas City Council voted 10 to five, with the mayor’s support, to give the downtown Dallas Hyatt Regency Hotel a nearly $3 million tax break to pay for expansion. “In a perfect world, we’d love not to have to abate anything,” the Dallas Morning News quotes the mayor as saying. “But in the real world, we’re in a war for jobs, businesses, development and families. This is a good deal.” It was an even better deal for the Hyatt’s primary downtown rival for large convention business, the Adam’s Mark Hotel, which had already received a $5.3 million tax break for renovations.31 However, hundreds of Dallas-area hotels and motels did not enjoy that tax break.

· Not only does Mayor Kirk hand out tax breaks to help business, he likes to ask for them. In the summer of 1997, Kirk and other urban leaders joined Vice President Al Gore to urge Congress to pass President Clinton’s proposal to provide cities with a number of different tax breaks. The president was asking for $858 million in tax incentives to help struggling areas, $41 million to encourage investment in financial institutions, and $331 million in tax credits for employers who hire people moving from welfare-to-work.32

While it’s possible to conclude that these breaks are reasonable and beneficial, Kirk’s support of them indicates that he is not motivated by the fairness argument alone. It isn’t whether someone gets a tax break, but who gets a tax break that is important to him.

The Economic Impact of Taxing the Internet

“Ideas have consequences,” said scholar Richard M. Weaver in a book by the same name; so do taxes. When government taxes a product or service, it raises the price and fewer people buy it. How much the new tax affects demand depends on a number of factors such as the size of the tax, the elasticity of the product (i.e., how willing people are to substitute a different product), and general economic conditions.

Access Taxes

Several states have imposed access taxes on Internet service providers. The size of the access tax has been relatively small—generally 5 percent or 6 percent, plus some local communities tacked on an additional 1 percent to 2 percent. Since ISP service charges are not expensive in most cases—America Online will run about $22 a month—the amount each consumer pays in tax is relatively small, probably less than $1.50 a month.

Would a tax of that size discourage people from signing up with an ISP in order to access the Internet, exacerbating the problem known as the “digital divide” (i.e., the already occurring situation in which higher-income and more educated people have computers and access to the Internet, while lower-income and those with less education don’t)?

While access taxes may discourage some lower-income people from accessing the Internet, buying the equipment and signing up with an ISP are much more daunting costs. Those whose incomes are so low that one or two dollars a month would make a difference probably are not buying new and powerful, Internet-capable computers in the first place.

One positive aspect of the access tax is that it is dispersed—charging a lot of people a relatively little amount of money. An access tax also is visible and predictable, meaning you know how much the tax will cost you each time, unlike sales taxes that can vary with the item and the location of its purchase.

How much revenue would an access tax produce? If 50 million households are online and paying an average of, say, $1.50 per month, or $18.00 per year, government would take in $900 million annually. However, that is only about .6 percent of total 1998 state sales tax revenues ($155.3 billion). So if the states are really concerned about losing revenue through Internet sales, taxing access will not recover much money.

Fortunately, there appears to be a growing recognition that the Internet’s primary value is as a source of information, and that taxing information, or access to information, is wrong in principle. As a result, several states that had imposed an access tax have suspended the law that implemented the tax, and there seems to be little desire to make it the Internet tax of choice.

Sales Taxes

Assessing the economic impact of taxing Internet sales is a daunting task because there is very little to compare it to and almost no previous scholarly analysis. Fortunately, Austan Goolsbee of the University of Chicago’s Graduate School of Business and the National Bureau of Economic Research has managed to make an assessment of the economic impact of Internet taxes.33

Goolsbee’s first task was to determine the consumers’ tax sensitivity (i.e., how willing they are to substitute an item with little or no tax for one with a higher tax). This type of work has already been done in border regions, where people have the opportunity to easily cross a border, say, into the next state, in order to pay a lower sales tax. Research has shown that people living in border areas are highly sensitive to taxes, according to Goolsbee.

The next step was to look at online sales in high-tax areas. “Controlling for individual characteristics, people who live in high sales tax locations are significantly more likely to buy over the Internet . . . . The estimated tax price elasticities of Internet commerce are large and resemble those found in previous studies of taxes in geographical border areas. The magnitudes suggest that enforcing existing sales taxes on Internet purchases could reduce the number of online buyers by as much as 24 percent.”34

Thus, Goolsbee thinks effectively imposing the current state sales and use taxes on Internet purchases could slow e-commerce by a quarter. Based on the projection that business-to-consumer sales, left unhindered, are predicted to reach about $108 billion by 2003, that would mean a reduction of $27 billion in the economy. And remember, people may not necessarily go to a brick-and-mortar store to buy the product if they can’t get a good price on the Internet. Some of that $27 billion will be lost economic growth.

Should the Internet Be Taxed?

While a consistent view of federalism and state sovereignty would acknowledge that states have the right—albeit limited by the Constitution and the courts—to tax Internet access, sales and perhaps other elements, that doesn’t mean they should. There is currently no economic reason for taxing the Internet nor is there a fairness reason.

States Are Financially Prosperous

According to the National Conference of State Legislatures, based on responses provided by 44 states:35

“ Conservative revenue forecasting and prudent fiscal management have left states in their best financial condition in decades.”

“ At the end of state fiscal year 1999, aggregate state ending balances were $33.4 billion.…Thirty-two of the reporting states ended FY 1999 with a balance exceeding 5 percent, the level Wall Street analysts recommend as prudent. Seventeen of these states ended with balances exceeding 10 percent.”

In addition:

· 17 states made deposits to their rainy day funds or other reserve funds;

· 20 states cut taxes specifically to reduce excess revenues;

· 13 states targeted certain programs for extra funding increases; and

· 13 states channeled surplus revenues into capital construction projects.

And with regard to tax cuts, the NCSL says, “State legislatures in 1999 lowered taxes for the fifth consecutive year, approving a net reduction of:”

Finally, states varied on the type of tax cut they provided.

· 24 states cut personal income taxes;

· 14 states cut corporate and business taxes; and

· 21 states reduced sales and use taxes.

Were states struggling for revenue, Dallas Mayor Ron Kirk’s comment about no one to answer the telephones during a crisis might make sense. But states and state budgets are experiencing unprecedented revenue growth. Most are looking for ways to return that money to tax payers. What economic or political sense does it make to create a new tax while they are trying to cut and eliminate already existing taxes?

There Are No Fair Taxes.

Theoretically, it is possible to create a level tax playing field that does not discriminate against certain types of vendors, products, services or the way in which a vendor markets his product (i.e., in retail stores, on the street, through catalogues, etc.). In reality, there are no fair taxes. Special interests are constantly trying to find ways to protect their own interests and maximize profits by seeking a special deal. For example, new cars usually have a lower sales tax than other products, and food and prescription drugs aren’t usually taxed at all.

In addition, politicians are increasingly pushing sweetheart deals by giving one business a tax break and not its competitor. Or one industry, or one geographical region. In fact, Clinton’s $350 billion tax cut package proposed in his last State of the Union Address provides targeted tax cuts to a wide range of individuals, families, businesses, organizations and special interests. His proposal declares that we are in an age of tax favoritism, not tax fairness. For example, Clinton wants to provide more money for “ empowerment zones,” which give tax breaks to businesses that move into low-income areas. Is that fair to the businesses that may be just across the street from an empowerment zone? One business gets a tax break—with the potential for those savings to be passed on to consumers in the form of lower prices, which would also hurt the competitor—and another doesn’t simply because of location? Yet most federal, state and local elected officials from both parties favor such targeted tax breaks.

If Utah Gov. Mike Leavitt, Dallas Mayor Ron Kirk and all of the government-oriented associations such as the National Governors’ Association and the U.S. Conference of Mayors really want to achieve tax fairness, they would be supporting the adoption of a flat income tax and the elimination of all other taxes and tax breaks. They are doing just the opposite.

So the states don’t need the additional revenue and there is no fair tax. That being the case, there is no justification for taxing Internet access or sales.

Conclusion

While states may have the right under current law to levy taxes on Internet access, use and sales, most don’t. And that’s the way it should be. There are some reasons for taxing the Internet; there are a lot more reasons not to. States don’t need the money—they are having difficulty giving back all of the extra money they already have. And there is no consistency from them when it comes to tax fairness. So there is little reason to believe that the states will get an Internet tax fair. And considering the harm a tax is likely to do to the growth and development of the Internet, it makes sense for the states—at least for now—to see the Internet as a tax-free zone.

Endnotes

1. “64.2 Million U.S. Adults Regular Internet Users,” Mediamark Research Inc., January 6, 2000.

2. Paul A. Greenberg, “Retailers React to Pressure from Online Shopping,” ; E-Commerce Times , January 20, 2000; and “Principles for Making Electronic Commerce Fair and Modernizing States Tax Systems for the 21st Century,” a paper submitted to the Advisory Commission on Electronic Commerce by the Council on State Governments, et al., November 1999.

3. “Principles for Making Electronic Commerce Fair and Modernizing States Tax Systems for the 21st Century.”

4. Joseph Brooks, Statement delivered to the Advisory Commission on Electronic Commerce, New York, September 15, 1999.

5. “17 Million U.S. Households to Shop Online in ‘99,” Forrester Research, September 29, 1999.

6. Paul A. Greenberg, “Retailers React to Pressure from Online Shopping,” ; E-Commerce Times, January 20, 2000.

7. “The Internet Economy Indicators,” University of Texas’ Center for Research in Electronic Commerce,” September 29, 1999.

8. Jonathan B. Weinbach, “Mail-Order Madness,” Wall Street Journal, November 19, 1999.

9. For an extensive discussion on these issues see Karl A. Frieden and Michael E. Porter, “The Taxation of Cyberspace: State Tax Issues Related to the Internet and Electronic Commerce,” Arthur Andersen Worldwide S.C., December 1996.

10. Robert J. Cline and Thomas S. Neubig, “Masters of Complexity and Bearers of Great Burden: The Sales Tax System and Compliance Costs for Multistate Retailers,” Ernst & Young Economics Consulting and Quantitative Analysis, September 8, 1999, p. Ii.

11. “Collecting Sales Tax over the Internet,” U.S. Conference of Mayors, www.mayors.org.

12. George Kuempel, “Dewhurst Seeks Change in Tax Rule,” Dallas Morning News, January 14, 2000.

13. Anne C. Mulkern, “Smokers Burned by Net Buying,” Orange County Register, January 15, 2000.

14. Dean Andal, “A Uniform Jurisdictional Standard,” Paper presented to the U.S. Advisory Commission on Electronic Commerce, September 15, 1999.

15. “Which States Tax Internet Access?” National Conference of State Legislatures, March 25, 1998.

16. John Moore, “Will You Pay Internet Polls?” Sm@rt Reseller, September 27, 1999.

17. For an extensive discussion of the NGA proposal see Adam D. Thierer, “The NGA’s Misguided Plan to Tax the Internet and Create a New National Sales Tax,” Heritage Foundation Backgrounder No. 1343, February 4, 2000.

18. “Streamlined Sales Tax System for the 21st Century,” National Governors’ Association, www.nga.org., p.1.

19. Proponents of the NGA plan recently suggested that they would drop the trusted third party provision.

20.Ibid., p. 2.

21. “Issues and Policy Options Paper,” Advisory Commission on Electronic Commerce, www.ecommercecommission.org, December 3, 1999.

22. Advisory Commsiion on Electronic Commerce, Draft Proposal, January 31, 2000.

23. Henry J. Aaron, “E-commerce Has Unfair Advantage,” Dallas Morning News, December 20, 1999.

24. Joseph Brooks, Statement delivered to the Advisory Commission on Electronic Commerce.

25. Jim Landers, “Main Street vs. e-Street on the Information Superhighway,” Dallas Morning News, January 30, 2000.

26. Kuempel, “Dewhurst Seeks Changes in Tax Rules.”

27. Cited in Gene Koretz, “Inflation’s New Adversary,” Business Week, October 4, 1999.

28. Joseph Guinto, “Is the Internet Killing Inflation?” Investor’s Business Daily, January 19, 2000.

29.Ibid.

30. Of course, eliminating the sales tax and replacing it with a corporate income tax could lead to higher retail prices, but there would be no sales tax on that price. Nevertheless, shoppers might still be confused and think the vendor with the lower sale price is the better deal without considering the impact of the sales tax.

31. Robert Ingrassia, “Council OKs Tax Breaks for Expansion,” Dallas Morning News, August 27, 1998.

32. Susan Feeney, “Gore Calls for GOP to Fund Urban Projects,” Dallas Morning News, July 8, 1997.

33. Austan Goolsbee, “In a World Without Borders: The Impact of Taxes on Internet Commerce,” Revised: July 1999.

34.Ibid., pp. 2-3.

35. “State Budget and Tax Actions 1999: Preliminary Report,” National Conference of State Legislatures, July 25, 1999.