Synopsis:

The health insurance system has failed America. Most of the blame lies with state and especially federal government intervention. Lawmakers have increasingly abandoned long-standing actuarial principles, culminating in the Affordable Care Act. The result is insurers are increasingly covering small and routine health expenditures and exposing patients to very expensive costs, turning the principle of health insurance upside down. Short of repealing Obamacare, Congress should give insurers enough flexibility to operate outside of the current restrictions.

Introduction:

The health insurance system has failed America. While health insurers played a role in that failure, most of the blame lies with federal and state government intervention and micromanagement—and arguably mismanagement. In essence, the more federal and state politicians and bureaucrats tried to improve access to quality, affordable health insurance, the less access people had—with the final blow coming from President Obama’s misnamed Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act.

Can the health insurance system be fixed? Maybe, but only if politicians are willing to let it function like real insurance rather than using it as a social justice tool to achieve their vision of “fairness”—and their chances of reelection.

How Insurance Is Supposed to Work—and Why

The principle behind any type of insurance is simple: People or businesses face a risk and want to avoid the full cost of that risk if it occurs. So, for example, individuals who want to limit the financial risk of death may buy life insurance. Those who want to reduce the risk of financial loss if their homes are robbed or destroyed buy property insurance.

In each case the applicant applies for coverage and the insurer assesses the risk the applicant brings to the insurance pool and charges a premium based on that risk—or declines to offer coverage if the risk is too high.

That’s why young people, who have a lower statistical risk of death, will typically have a lower life insurance premium than older people. On the other hand, older adults may face lower auto insurance premiums than younger people, especially males, who tend to be more aggressive drivers.

Underwriting insurance policies has been a very successful model backed by centuries of experience. Insurers’ ability to decline coverage or charge high-risk applicants more encourages individuals and companies to enter the insurance pool before an unforeseen incident occurs and avoid risky behaviors, both of which are essential for a stable insurance market.

Why Health Insurance No Longer Works

Most insurance markets—life, property, auto, etc.—still rely on standard actuarial principles. Not health insurance.

While health insurance pre-dated World War II, it began expanding during the war when employers, who couldn’t boost wages because of wage and price controls, began offering health coverage to attract good workers. That expansion gained momentum when the IRS ruled in 1943 that employer spending on coverage would be tax-free to the employee—a “tax exclusion” because the money spent on coverage is excluded from income.

That coverage was essentially hospital coverage, which represented the primary financial risk in health care. But because employer-provided health insurance is excluded from personal income tax, and because workers (incorrectly) believe the cost of coverage comes out of the employers’ pocket rather than their own, workers and their unions wanted more of it. The result is, over time, employer-provided coverage became more and more comprehensive, increasingly insulating employees from the cost of care.

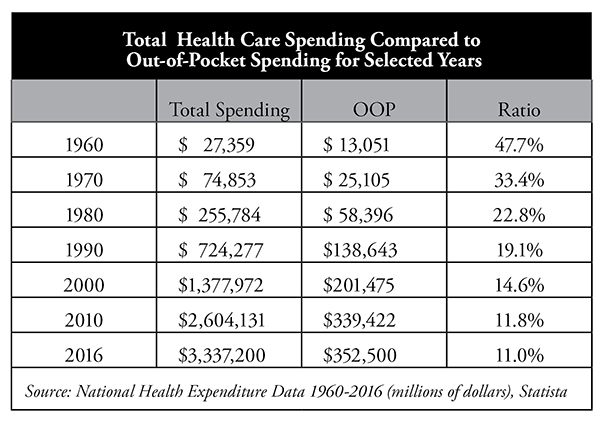

As the table shows, in 1960 patients paid nearly 48 percent of all health care spending out of pocket (OOP). By 2016, total out-of-pocket spending had declined to about 11 percent. However, after the implementation of the Affordable Care Act in 2014, with its very high (and growing higher) deductibles—especially for bronze-level plans—and other coverage changes, out-of-pocket spending is likely to rise again.

That decades-long trend toward lower OOP spending fundamentally changed the nature of health insurance and the way people consume health care. Patients simply had little reason to worry about health care prices or how much they were spending.

The Government Gets Involved

Historically, insurance was regulated at the state level, yet states initially refrained from imposing a heavy thumb on health insurance. However, over time patients and providers representing a wide range of medical conditions and services began lobbying their state elected officials to cover their special interests. The effort worked.

States increasingly began to mandate that health insurance cover specific providers or medical conditions. That list of mandates grew from a handful in the 1960s to 2,271 by 2012, the last year the Council for Affordable Health Insurance published its state mandate tracker.1

Those mandates covered all types of providers and services from the most important to the marginal. For example, three states required the coverage of “oriental medicine,” two states mandated “port wine stain elimination,” three covered “athletic trainers,” and four “naturopaths.” Thirty-four states required the coverage of “drug abuse treatment,” even for teetotalers.

While there is nothing wrong with patients wanting or using these services, insurers typically did not cover them. State governments forced them to do so, which began pushing up the cost of health insurance and creating an unintended problem: increasingly unaffordable coverage.

However, even as the states were increasing their regulatory efforts, the federal government largely steered clear of health insurance regulation. The Employee Retirement and Income Security Act of 1974 (ERISA) gave the federal government some say in the regulation of employer-provided health insurance. Importantly, ERISA also allowed large employers that self-insure—i.e., the employer rather than insurers bears the claims risk—to avoid nearly all state-imposed health insurance regulations.

Everything began to change when President Bill Clinton tried to pass comprehensive health care reform in 1993, referred to as ClintonCare. The legislation failed, but the effort opened the door for Congress to become increasingly involved in health insurance. In 1996 Congress passed its own federal health insurance mandate: the Newborns’ and Mothers’ Health Protection Act, which restricted health insurers from limiting how long a mother having just given birth could stay in a hospital.

Congress also passed in 1996 the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA), which imposed numerous restrictions on health insurance, established certain privacy practices and created Medical Savings Accounts (the forerunner of Health Savings Accounts).

In short, the gate for federal health insurance regulation was pushed wide open. By the time President Obama and Democrats began drafting the Affordable Care Act, Democrats in Congress not only considered it appropriate to micromanage the health insurance system, they saw it as imperative.

Perverse Economic Incentives Drive the System

Today, health insurance and the health care system are driven by perverse economic incentives. The people who deliver the care aren’t, in most cases, paid by the patients who receive that care. They’re paid by a third party (insurers, employers or the government), which has a greater interest in the cost than the quality of care. Patients have very little incentive to ask how much their care will cost, and providers likely couldn’t tell them anyway—because they don’t know.

The third parties paying the bills have every economic incentive to closely monitor the cost of care, and they often impose restrictive guidelines on health care providers to keep costs down. In addition, insurers keep reducing the number of providers that patients are allowed to see, disrupting the doctor-patient relationship.

Since the payers are primarily concerned with containing costs, middlemen such as pharmacy benefit managers (PBMs) have emerged, claiming they can negotiate steep discounts and squeeze out savings. Unsurprisingly, the middlemen apparently keep much of those “savings” for themselves.2

The way hospitals price care has also become another major point of contention. The government’s Medicare and Medicaid programs essentially dictate what they will pay hospitals for specific procedures and products, including prescription drugs and medical devices. That reimbursement is typically much lower than hospitals’ “list price.”

Wanting in on the discount action, insurers and managed care organizations began negotiating their own discounts off the hospitals’ list price. Hospitals responded by increasing their prices so they could negotiate from a higher number and by consolidating to increase their market strength, a trend greatly exacerbated by Obamacare.

For example, Wall Street Journal reporter Anna Wilde Matthews recently wrote:3

Dominant hospital systems use an array of secret contract terms to protect their turf and block efforts to curb health-care costs. As part of these deals, hospitals can demand insurers include them in every plan and discourage use of less-expensive rivals. Other terms allow hospitals to mask prices from consumers, limit audits of claims, add extra fees and block efforts to exclude health-care providers based on quality or cost.

Today, many hospital prices bear no relation to what it costs the hospital to actually provide the service. The list price for the same procedure can vary widely from hospital to hospital, and it can easily be five times or more than what a Medicare or privately insured patient will actually pay.

And the worst part is that an uninsured person will likely be hit with the full, undiscounted price (or close to it), even though the uninsured are usually the least able to afford it.

Obamacare Doubles Down on Bad Economic Incentives

The Affordable Care Act doubled down on the decades-long trend of insulating patients from the cost of care. It requires health insurers to cover even the most routine and discretionary of costs, such as standard physicals and all forms of birth control, with no out-of-pocket charge to the patient.

But that’s not all. Obamacare also ignored standard actuarial principles by eliminating underwriting in the individual health insurance market. Health insurers are now required to accept anyone (guaranteed issue), regardless of a preexisting condition, and cannot charge them a higher premium based on their illness (community rating).

The result? The uninsured who were sick quickly applied for coverage, while the young and healthy would be more likely to remain uninsured until they are sick. Premiums must rise to cover the additional number of sick, which drives out more young and healthy people, which pushes premiums even higher. Insurers refer to this process as “adverse selection,” when the insurance pool has a disproportionately high number of sick people.

Most in the health insurance industry had long opposed guaranteed issue and community rating, because insurers knew those mandates would undermine the individual health insurance market. But during the Obamacare debate, the head of the health insurers’ largest trade association, a longtime Democrat, led insurers in supporting the legislation.

Obamacare’s drafters tried to mitigate the adverse-selection potential by (1) mandating people have coverage; (2) imposing a penalty (i.e., tax) if they didn’t; (3) limiting the times a person could enroll to just a few weeks a year; and (4) providing hundreds of billions of dollars in subsidies, making insurance “free,” or nearly so, for millions of people.

But to be effective, the penalty would have to be very large and the ability to receive an exemption very limited. Neither was the case. The penalty was relatively small compared to the cost of coverage, and bureaucrats created numerous penalty exemptions. As a result, only about a quarter of the 29 million uninsured had to pay the tax.4

Obamacare never attracted the number of young and healthy people government analysts predicted, which meant the pool was smaller and sicker, leading to significant premium increases to cover the costs.5 The only thing that may prevent the exchanges from collapsing completely is the subsidies. Why would an Obamacare enrollee care how much their premiums are if taxpayers are covering most or all of the costs?

These developments were completely predictable; indeed, experts predicted them. Many of the largest insurers began pulling out of the Obamacare exchanges within just a few years. Others began adjusting their coverage options and limiting provider networks in a desperate effort to save money.

Health Insurers Limit Care

Most people spend little or nothing on health care in a given year; a relatively small number spend a lot. Insurers make money on the former and lose it on the latter. Since under Obamacare insurers cannot charge more to those with high expected costs, they have every incentive to discourage the sickest patients from enrolling—or encourage them to leave if they’re already in.

How would insurers do that since Obamacare prohibits them from canceling those policies or denying coverage? Adjust insurance coverage options so that certain unprofitable patients have to pay more out of pocket—especially those with expensive and chronic care needs.

For example, insurers may claim that certain diagnostic tests are not actually diagnostic tests, and therefore not covered. Or they may impose prohibitive cost-sharing on very expensive prescription drugs. In years past, insurers charged one copay for a generic drug, say $10, and a slightly higher copay for a brand name drug, such as $20 or $25.

No more. Health insurers moved to three tiers and then four tiers and some to five tiers. The generic might still require a $10 copay and a brand name $25. But some drugs may be placed in a third tier, with a copay between $50 and $250.

However, it’s the fourth and fifth tiers that may be unaffordable for most patients if an insurer requires co-insurance of, say, 20 percent to 40 percent of a drug’s cost. For example, if a drug costs $5,000 a month—and some cancer drugs cost that much or more—40 percent co-insurance could cost the patient several thousand dollars a month. And that comes on top of other health care-related expenses and premium costs.

Some groups have complained when they discovered insurers engaging in what they believe are disease-discrimination practices, because such practices undermine Obamacare’s guaranteed issue provision. What good is having “comprehensive health coverage” if targeted patients face thousands of dollars a month in out-of-pocket expenses?

According to Kaiser Health News:6

- In 2016, Harvard Law School’s Center for Health Law and Policy Innovation filed complaints with the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services’ Office for Civil Rights alleging that health plans “offered by seven insurers in eight states are discriminatory because they don’t cover drugs that are essential to the treatment of HIV or require high out-of-pocket spending by patients for covered drugs.”

- In 2014 the AIDS Institute and the National Health Law Program filed complaints against four Florida health insurers alleging “the insurers placed all the HIV drugs in the highest cost-sharing tier.” The Florida insurance commissioner eventually reached an agreement with the health plans to put the drugs in generic tiers.

- Consulting company Avalere Health found that several insurers’ silver plans had been adversely targeting some of the sickest populations with higher drug costs. “An analysis found that in the case of five classes of drugs that treat cancer, HIV and multiple sclerosis, fewer silver plans in 2016 placed all the drugs in the class in the top tier with the highest cost sharing or charged patients more than 40 percent of the cost for each drug in the class.” Notice that while Avalere suggests some insurers had abandoned the practice, many had not.

Charging some of the sickest patients much more for prescription drugs helps health insurers in at least two ways: It saves health insurers money and it encourages the targeted patients to drop their current insurer during open enrollment and switch to an insurer with a more generous—or rather, less onerous—drug benefit.

Insurers Restructure Coverage Options

While President Obama promised health insurance premiums for a family would decline by $2,500 a year, no knowledgeable health policy person believed that. It was very clear his abandonment of actuarial standards would lead to premiums rising substantially, which is exactly what happened.

In an effort to control those runaway costs, health insurers began restructuring their policies, including increasing OOP costs and adjusting coverage options—all within Obamacare’s “actuarial values.” They also began limiting the number of approved providers—the so-called “skinny networks”—perhaps because those providers agreed to be paid less, may have practiced more “conservatively,” or were more willing to follow insurers’ guidelines.

Several insurers even went to “exclusive provider networks,” meaning the health insurer would not reimburse a patient for care received outside of the insurer’s provider network. And some insurers have refused to cover emergency room visits the insurer considered “avoidable.”

For example, the New York Times reported in July that Anthem Blue Cross “initially rolled out the policy in three states, sending letters to its members warning them that, if their emergency room visits were for minor ailments, they might not be covered. Last year, Anthem denied more than 12,000 claims on the grounds that the visits were ‘avoidable’…"7

How an untrained person is supposed to know when an emergency room visit is “avoidable” is left unexplained.

In fairness to the insurers, had they not begun making significant coverage adjustments, health insurance premiums would have risen significantly higher than they have. But it also means that insurers are abandoning their primary function: protecting patients from catastrophic losses. The whole idea of insurance has been turned upside down.

Attracting the Healthy

It’s not just finding ways to discourage the sick from enrolling; insurers have an economic incentive to encourage the healthy to enroll. That’s not an easy task in the age of Obamacare, in which traditional underwriting is outlawed, because insurers can’t offer the healthy lower premiums. But they might add benefits, such as a free gym membership, intended to attract healthy people.

The Las Vegas Review-Journal ran a story in 2016 about benefits you might not know your health plan included. “Fitness tracking and management is one increasingly popular benefit …. And some companies are going beyond merely offering deals or reimbursements for gym memberships.”8

Analyst Kathryn Hawkins notes that several health insurers are offering free or discounted gym memberships, and adds, “Covering gym membership is a plus for health insurance providers, too: By advertising the perk in their marketing materials, insurance providers are likely to attract a healthier segment of the population, which will lead to lower claim rates.”9

Back in the 1990s, I spoke with the person in charge of managing the Federal Employees Health Benefits Program (FEHBP), the health insurance program available to federal employees and their dependents. Like Obamacare—in fact, the FEHBP was something of a model for the Obamacare exchanges—federal employees could change plans annually during what’s called “Open Season.”

The FEHBP administrator told me that one of the participating health insurers began offering free pediatric dental care as part of the coverage package, which seemed like a nice benefit. But he ordered the insurer to end that coverage immediately. He claimed it was a thinly vailed attempt to attract families with young children, who would tend to be younger and therefore better risks.

The point is, when insurers are forced to accept anyone—and FEHBP-participating insurers must accept any qualified federal employee who applies—they may look for subtle ways to attract a healthier population and avoid the sickest.

The Height of Hypocrisy

While it may be understandable why health insurers need to take steps to reduce their costs, targeting some of the sickest patients in the hope they will leave the plan, or never join in the first place, represents the height of hypocrisy.

Health insurers were well aware that guaranteed issue and community rating would lead to adverse selection—because they had so long warned about that danger. Yet they decided to embrace Obamacare anyway. Thus they should cease and desist any efforts to discretely cherry-pick the better risks.

Health Insurance That Is No Longer Insurance

Here’s the irony: The purpose of health insurance has been flipped on its head.

Health insurance (like any insurance) is supposed to protect us from catastrophic losses. Under Obamacare’s regulatory onslaught, insurance increasingly protects patients from costs they could easily pay, while exposing them to costs they could never afford—on top of the sky-high premiums.

Obamacare requires that all contraceptives be available free, even though most of them are inexpensive and could be easily paid for out of pocket by the vast majority of women. But if someone is diagnosed with cancer and the doctor prescribes an amazing new drug that will cost several thousand dollars a month, cancer patients may find their insurance leaves them exposed to very high costs.

Ultimately, consumers are paying more and more for less and less. They are more exposed to high out-of-pocket costs, both in deductibles and co-insurance, than ever before. Health insurance, especially in the individual market, which is largely dominated by the Obamacare exchanges, has failed America.

Is There a Solution?

Republicans have failed to repeal Obamacare, and it seems unlikely at this point a successful repeal-and-replace effort will be mounted. Indeed, many if not most Republicans now support the guaranteed issue provision in Obamacare.

There is a better way of providing access to affordable coverage for uninsured individuals with preexisting conditions—a high risk pool, whether run by individual states or by the federal government, based on best practices. However, it appears unlikely guaranteed issue and community rating will be repealed, which leaves us with tweaking the current system.

President Trump has taken several positive steps to try and mitigate the damage. He has asked the Department of Health and Human Services to consider ways to provide insurers and states more flexibility in plan design. He has encouraged the development of association health plans and expansion of short-term policies. And Congress eliminated the penalty for not having Obamacare-qualified coverage beginning in 2019.

Those are positive steps, but more can and should be done.

Short-Term Policies

The Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) is restoring, and even expanding, so-called “short-term, limited-duration plans” to their pre-Obamacare days. People will be able to buy the policies, which tend to be very basic, and retain them longer. That’s a good step.

Now insurers need to step up and develop short-term plans that are more comprehensive than currently being offered. Prior to Obamacare, the plans were very limited, which was fine because consumers had access to a wide range of health insurance options. No longer. Obamacare prohibits insurers from offering any type of comprehensive coverage that isn’t Obamacare-qualified.

However, short-term policies are exempt from Obamacare coverage mandates. And in many cases they are exempt from state mandates, most of which remain in effect. With a little tweaking by the insurers, short-term policies could become the basic health insurance option that most people buying their own coverage need and want.

The HSA Option

There has been a small but important health care trend countering the long-term effort to expand insurance and reduce out-of-pocket spending. For several years some insurers and employers have offered high deductible health insurance policies, often combined with a Health Savings Account (HSA), i.e., tax-free funds used to pay for qualified health care expenses.10 In other words, there has been a movement to return health insurance to real insurance, which covered unforeseen, catastrophic medical events while individuals paid routine costs out of their tax-free HSAs.

According to the Employee Benefit Research Institute, about 80 percent of large employers and 25 percent of small employers offered an HSA or Health Reimbursement Arrangement (HRA) option in 2016.11 That increased access has led to larger take-up rates. There were some 800,000 HSA accounts in 2011. By the end of 2016 there were about 5.5 million HSAs, holding some $11.4 billion.

There are efforts to expand HSAs so anyone with high deductible coverage would be qualified to have one, and provide more flexibility for their usage. And the Cato Institute supports an idea called “large HSAs,” which would allow employers to put the money they are spending on health insurance into a tax-free HSA for employees, who could spend the money both on insurance (including the employer’s plan) and health care.12

Direct Pay

There is also a small but growing movement to allow “direct pay.” While the specifics can vary, it generally means paying doctors directly and bypassing most or all insurance. That option removes health insurance, including its restrictions and administrative costs, from the vast majority of most people’s health care decisions.

And it addresses another problem identified in this paper: access to real pricing information. As the Wall Street Journal recently pointed out, patients often have no idea how much their care—including doctors’ charges, labs and diagnostic tests, hospital care and prescription drugs—will cost them. Stranger yet, neither do most health care providers. That’s one of the major failings of the current health insurance system. However, direct-pay practices generally do have clearly stated prices, allowing patients to become value-conscious consumers.

Promote Supplemental Coverage

Because individuals can be exposed to very high out-of-pocket health care costs, they may want something to cover those expenses. Many life insurance companies sell term policies with an accelerated benefit in case of a major accident or critical illness. Essentially, the insurer writes a check to the insured if a major medical condition occurs. Doing so reduces the value of the policy or cancels it—depending on how much the insured receives.13

If the insured never draws on the life insurance policy—and most people likely wouldn’t—the amount of life insurance would remain in effect until death or until the person drops the policy.

But if the insured is diagnosed with, say, cancer and some of the newest cancer-fighting drugs might help, the patient could draw on his or her life insurance benefits to help cover those costs.

While life insurance policies with an accelerated-benefit option have been available for some time, most people are unaware of them. Insurers need to start marketing such policies as a safety net for those who face high out-of-pocket costs.

Block Grant ACA Money to the States

Conservatives and many Republicans have long called for block granting federal Medicaid money to the states and giving them the flexibility to experiment and innovate within the program. And Republicans included that provision in their repeal-and-replace proposals.

However, a new proposal suggests going a step further, block granting to the states both federal Medicaid expansion money and the funds spent on Obamacare subsidies.14 Since Washington has done such a terrible job trying to fix the health insurance system, maybe it’s time to give the states a chance. How much worse could they do?

Of course, it is likely that some states would do a good job and others not so much. But that’s one way to find out what does and doesn’t work. What we know is health insurance under the Affordable Care Act has been a dismal failure for millions of individuals buying coverage on the Obamacare exchanges.

Conclusion

The health insurance system has failed America. Premiums are outrageously high. There is virtually no transparency in the system. And it is almost impossible for patients to find out how much a health care procedure will cost them.

Health insurance isn’t the only failure. Hospitals are also a problem. Many charge outrageously inflated prices, especially to the uninsured. Most insured patients receive a steep discount, which only makes the pricing schemes appear contrived and artificial.

President Donald Trump is trying to address these problems. Nominating Dr. Scott Gottlieb, who has a long history of advocating for free markets, competition and transparency, to head the Food and Drug Administration was a good start. And the president’s efforts, backed by Health and Human Services Secretary Alex Azar, to provide health insurers with more flexibility is also helpful.

Whether the Trump administration’s incremental changes will be enough to allow a well-functioning health insurance system, at least in the individual market, to emerge is yet to be seen. But we know the current system has failed, and the primary reason is the government’s desire to ensure everyone had access to affordable coverage.

It is time for health insurers to devise new options, such as expanding short-term policies’ coverages, so Americans can once again have affordable coverage that actually protects them from catastrophic health care costs.

Endnotes

1. “CAHI Identifies 2,271 State Health Insurance Mandates,” PR Newswire, April 9, 2013. https://www.prnewswire.com/news-releases/cahi-identifies-2271-state-health-insurance-mandates-202179231.html

2. See, for example, Merrill Matthews and Peter Pitts, “Selective Transparency: Transparency Efforts Obscure Real Health Care Pricing Issues,” Institute for Policy Innovation, Issue Brief, May 2017.

https://www.ipi.org/docLib/20180517_Selective_Transparency.pdf

3. Anna Wilde Matthews, “Behind Your Rising Health-Care Bills: Secret Hospital Deals That Squelch Competition,” The Wall Street Journal, September 18, 2018. https://www.wsj.com/articles/behind-your-rising-health-care-bills-secret-hospital-deals-that-squelch-competition-1537281963

4. K.K. Rebecca Lai and Alicia Parlapiano, “Millions Pay the Obamacare Penalty Instead of Buying Insurance. Who Are They?” New York Times, November 28, 2017. https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2017/11/28/us/politics/obamacare-individual-mandate-penalty-maps.html

5. “Health Insurance Exchanges 2018 Open Enrollment Period Final Report,” Department of Health and Human Services, April 3, 2018. https://www.cms.gov/newsroom/fact-sheets/health-insurance-exchanges-2018-open-enrollment-period-final-report

6. Michelle Andrews, “7 Insurers Alleged to Use Skimpy Drug Coverage to Discourage HIV Patients,” Kaiser Health News, October 18, 2016. https://khn.org/news/7-insurers-alleged-to-use-skimpy-drug-coverage-to-discourage-hiv-patients/

7. Margot Sanger-Katz and Reed Abelson, “A Health Insurer Tells Patients It Won’t Pay Their E.R. Bills, but Then Pays Them Anyway,” New York Times, July 19, 2018. https://www.nytimes.com/2018/07/19/upshot/anthem-emergency-room-bills.html

8. Carolyn Benton, “10 Benefits You Didn’t Know Most Health Plans Cover,” Las Vegan Review-Journal, February 26, 2016. https://www.reviewjournal.com/business/10-benefits-you-didnt-know-most-health-plans-cover/

9. Kathryn Hawkins, “Does Health Insurance Pay for a Gym Membership?”, Insurance Quotes, May 6, 2013. https://www.insurancequotes.com/health/health-insurance-gym-membership

10. Known as a Medical Savings Account prior to the 2003 Medicare Modernization Act, which reformed MSAs into HSAs.

11. Paul Fronstin,” Trends in Health Savings Account Balances, Contributions, Distributions, and Investments, 2011‒2016,” Employee Benefit Research Institute, No. 434, July 11, 2017. https://www.ebri.org/pdf/briefspdf/EBRI_IB_434_HSAs.11July17.pdf

12. Michael F. Cannon, "Members of Congress Introduce Cato's 'Large HSA's' Concept, June 2, 2016.https://www.cato.org/blog/five-things-you-need-know-about-bicameral-legislation-creating-large-hsas

13. Merrill Matthews, "A Viable, Affordable Alternative to Obamacare," Forbes.com, October 14, 2015.https://www.forbes.com/sites/merrillmatthews/2015/10/14/a-viable-affordable-alternative-to-obamacare/#5aa796ea42fe

14. Health Policy Consensus Group, "The Health Care Choices Proposal: Policy Recommendations to Congress, June 19, 2018.https://www.healthcarereform2018.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/06/Proposal-06-19-18.pdf