Introduction

The state-by-state regime of insurance regulation in the United States has been stuck in New Deal amber for the past six decades. Two outdated economic presumptions left over from the New Deal continue to underpin and bedevil the regulation of insurance:

- Markets are fragile, constantly failing and forever harming consumers. Therefore, markets are in continuous need of government fine tuning and restriction lest they do immeasurable harm to society; and

- The insurance busin ess is so sensitive to variable local conditions and circumstances that a national regulatory regime cannot possibly serve consumers ’ interests adequately.

These two New Deal presuppositions, on which our extensive and highly decentralized system for regulating the insurance industry rests, not only have been proved demonstrably false in case after case but have been supplanted since the end of World War II by more realistic (and principled) paradigms: in the case of virtually every industry other than insurance.

Both of the old New Deal assumptions ignore the dramatic change in economic circumstances that characterizes the past 20 years. Since the fall of communism, markets are flourishing around the world, and the global economy has become electronically networked and tightly integrated. Capital flows across international boundaries at will. Business transactions occur at the speed of light without regard to the location of the parties.

Despite these revolutionary changes to the manner in which firms do business and customers make purchases, regulatory bureaucracies have been very, very reluctant to adapt. While businesses and consumers operate in a networked, global environment, they must purchase risk management products from businesses that remain heavily regulated by 50 state bureaucracies, each of which varies widely in scope and method of implementing its regulatory vision.

The Debate Over Insurance Regulation: Where Deliberations Stand Today

As the divergence between these erroneous assumptions about markets (and insurance markets in particular) and actual economic reality grows ever greater, the need for regulatory reform, relief and modernization of the insurance industry is becoming evermore self evident. For example:

I. The United States Treasury Department currently is conducting a review of the regulatory structure for all financial services, including insurance in particular. It is asking many of the right questions. Specifically:

- What are the costs and benefits of state-based regulation of the insurance industry?

- What are the key federal interests for establishing a presence or greater involvement in insurance regulation? What regulatory structure would best achieve these goals/interests?

- Should the states continue to have a role (or the sole role) in insurance regulation? Insurance regulation is already somewhat bifurcated between retail and wholesale companies (e.g., surplus lines carriers). Does the current structure work? How could that structure be improved?

IPI recently submitted comments to the Treasury as part of the Department’ s review.1

II. The National Association of Insurance Commissioners (NAIC) is preparing to release a report and recommendations offering state regulators ’ views on changes to the regulatory structure they believe are warranted to the regulatory framework that governs the conduct of business for Property and Casualty Insurance. IPI also submitted comments on the draft NAIC report. 2

III. In October 2007, the House Committee on Financial Services held several days of hearings —the first in what promises to be a series of hearings— on the question of reforming the way insurance is regulated. Subcommittee chairman Paul Kanjorski (Subcommittee o n Capital Markets, Insurance and GSEs) summarized the situation: 3

The insurance regulatory structure has remained relatively constant throughout our Nation ’ s history, but nearly all interested parties now agree that some sort of regulatory reform is appro priate given global competitiveness, market pressures, and consumer demands. This hearing will explore why there is a need for insurance regulatory reform.

IPI has submitted testimony to the Committee for inclusion in the record of the next committee hearing.

The Debate Over Insurance Regulation: An Economic Perspective

This world runs on unintended consequences. No matter how noble your intentions, there ’s a good chance that in solving one problem, you’ ll screw something else up. —Rand Beers, Member of the National Security Council of four presidents

Speaking at a recent IPI briefing, guest speaker William McCartney of USAA argued that the growing interest in reform is being driven by two basic facts:

- U.S. insurers wishing to operate on the world stage are hampered by restrictive regulation that their international competitors do not face; and

- The flow of new capital in the insurance industry is moving in one direction —offshore to jurisdictions with more rational regulatory systems.

In this sense, the need for regulatory reform of the insurance industry is being driven by the same forces of global competition that compel us to reconsider the Internal Revenue Code and other regulatory structures that affect the ability of American busi nesses and workers to be as efficient and competitive as possible in today’ s global environment.

In addition, the necessity of a comprehensive regulatory review is becoming more obvious as states such as Florida begin using unfettered state regulatory powers in a predatory fashion to transfer risk and financial exposure from one group of local consumers and state treasuries to federal taxpayers, as well as the taxpayers of their own state(s) who are not at comparable risk. When Florida clamped down stringent price controls on property and casualty insurance policies, insurance companies responded by canceling many property and casualty policies and in some cases leaving the Florida insurance market altogether.

As a consequence, the State of Florida tried to pick up that coverage at below-market premiums through the state-run Citizens Property Insurance Company, thus shifting financial exposure away from those specific homeowners at risk of wind damage onto state taxpayers in general. This practice resulte d in the State of Florida ’ s assumption of actuarially unsound risk, which left Florida taxpayers exposed to enormous unfunded contingent liability claims. 4

Members of Congress from Florida, joined by Members from other at-risk states then began agitating for federal legislation to further transfer some of that risk from Florida taxpayers to taxpayers across the entire nation —a classic instance of rent seeking. 5 They succeeded in convincing the U.S. House of Representatives to pass legislation (“Homeowners ’ Defense Act of 2007”) that presumes to ease the provision (and cost) of home insurance in so-called “disaster-prone” areas (i.e., floods plains, geological fault lines, hurricane zones and wild-fire ranges). This legislation is supposed to empower Flori da and other states similarly situated (risk-prone and averse to letting market forces do their job) pool their collective risks as backing for marketable bonds and reinsurance. Those instruments would get federal (i.e., American-taxpayer) guarantees to ba ck them up—call it “Subprime Insurance.” 6

These pressures for regulatory reform and modernization are heightened with regard to insurance because unlike other areas of the economy, which have gone through extensive regulatory reform since the New Deal, t he regulatory framework of the insurance industry has changed hardly at all since the end of World War II. There is a compelling need to modernize today ’s outdated and dysfunctional state insurance regulatory system.

In addition to the work on insurance reform done at IPI, other national think tanks also have documented in considerable detail the problems and inefficiencies created by the current dysfunctional regulatory regime governing insurance. 7 A vivid and disturbing picture of the central problem with insurance regulation emerges from the research:

The insurance industry in the United States is regulated under an elaborately decentralized system of price controls imposed on a state-by-state basis. As the imposition of price controls distorts price signals and disrupts markets, serious ancillary problems arise. Each state regulatory bureaucracy responds in turn by devising its own elaborate web of regulations, subsidies and rationing in ill-fated attempts to mitigate the scarcities, higher cost, risk shifting/rent seeking and government-induced moral hazard that inevitably result whenever government drives a wedge into the marketplace with price controls.

Regulators as Predacious Do Gooders

Many people want the government to protect the consumer. A much more urgent problem is to protect the consumer from the government.—Milton Friedman

Experience demonstrates that whether it’ s gasoline, bread, prescription drugs or insurance, government price controls don ’ t work and end up causing many problems worse than the problem they were designed to remedy. It ’s a vicious cycle.

The regulatory industry (and it is an industry) has become sensitive to the mounting empirical evidence that they are engaged in a fool ’ s errand. In response, the regulatory industry goes to great lengths to distinguish between so-called “rate regulation” and price controls, but that is a false distinction without a difference. 8

The entire system of “rate regulation,” which provides the foundation of the insurance regulation industry, rests on an unwarranted and unsubstantiated assertion that markets cannot do more than approximate the “right” price of insurance. If markets were left free to operate on their own, regulators insist, consumers would be “over charged” and “underinsured.”

How the political process, and the technocratic regulators who are its product, can discern the “right” price is left unexplained. Moreover, rate-regulating bureaucrats fail to explain how exactly they better than markets can determine what the “right price” of insurance is or by what standards or principles that price is to be arrived at; or, indeed, how and why markets fail to deliver price information superior to what their regulatory schemes can provide.

The empirical evidence, however, is unambiguous. 9 Whenever regulators attempt to set the price of a good or service through price controls, shortages emerge, black markets develop, the real price (as opposed to the posted statutory price) of the good or service rises, which then compels government regulators and legislators to intervene yet again with an extensive regulatory police apparatus in an ill-fated effort to squelch black markets and solve the new set of problems created by the price controls. Thus, there are never-ending problems for regulators to grapple with, all self created and all redounding to the detriment of consumers.

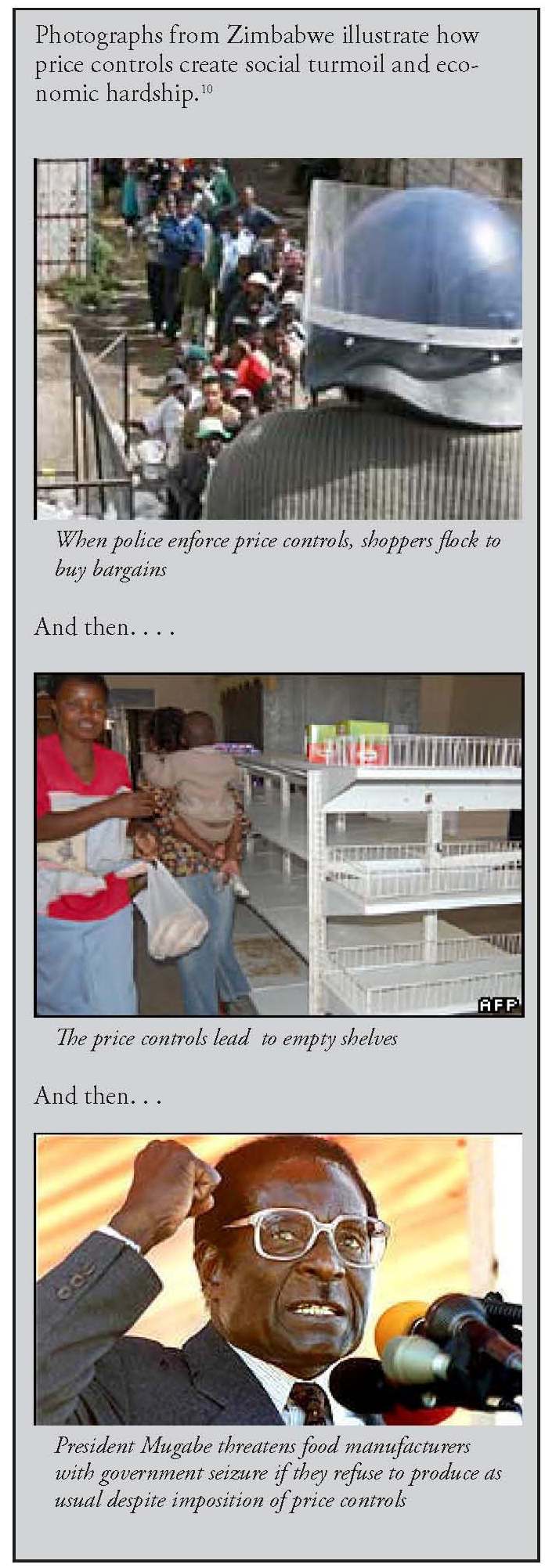

For example, this summer in Zimbabwe as price controls dried up the supply of food and emptied grocery store shelves, president Robert Mugabe threatened manufacturers that if they refused to carry on with normal production despite the official price freeze, he would order the government to

seize firms that stopped producing basic goods.

The State of Florida again illustrates the same viscous cycle when regulators act like predatory do gooders. When property and casualty insurance carriers raised rates in 2006 in Florida after the heavy wind damage that occurred in 2004 and 2005, homeowners squealed, and the state insurance commission and legislators responded. By mid-2007, the State of Florida had required private insurers to reduce premiums by approximately 25 percent and had allowed the unfunded contingent liability for wind damage to be spread among all Florida taxpayers by allowing homeowners to purchase insurance from a publicly owned company that could not come anywhere close to covering expected claims through premiums and investment income.

Insurance companies in Florida reacted t o the government’ s price fixing of insurance premiums exactly the way food producers reacted to price controls in Zimbabwe. By illustration, in July, 2007, State Farm Insurance Company (the largest provider of homeowners insurance in the State of Florida w ith more than one million homeowner policies) notified Florida’ s Office of Insurance Regulation of its plans to drop about 50,000 home-owners policies in 2008 in coastal areas it considers being of high risk to wind damage. The company said such policy can cellations were necessary if it were to continue doing business in Florida under current stringent price controls. 11

When food producers in Zimbabwe chose to stop producing food rather than continue to do so at prices that would not cover their costs of production and distribution, President Robert Mugabe threatened outright to seize their companies. American insurance regulators and state politicians are not so crude.

Instead, politicians and bureaucrats typically resort to a form of extortion, threat ening, for example, to rescind companies’ rights to offer other lines of insurance in the state if the firm refuses to offer homeowners insurance in the state. At the same time, state regulators and legislators frequently use publicly-owned insurance companies as a cat ’ s paw to engage in predatory pricing, which if conducted by a private firm would be subject to prosecution under the antitrust laws of most states. 12

In Florida, for example, the legislature required the state-owned Citizens Insurance Compan In Florida, for example, the legislature required the state-owned Citizens Insurance Compan y to match the rates private insurers are mandated to charge under Florida price controls. Hence, rather than seizing insurance companies who don ’ t play ball, Florida simply threatens to drive them out of business with predatory practices reminiscent of the Age of the Robber Barons prior to anti-trust legislation. Politicians like to call this kind of practice “harnessing the market to achieve public purposes.” In fact it is a form of uncompensated regulatory “taking” performed under the color of “state interest.” 13

In this way, government-owned insurance firms such as Florida’ s Citizens Insurance Company, initially justified as an “insurer of last resort” to cover risk private companies would not touch, increasingly will become the insurer of “first” re sort. Perversely, such publicly owned companies will do even more business at the state-mandated, actuarially unjustifiable rates.

The great difference is that in the Age of Robber Barons, there were few legal barriers to entry, and eventually competitive forces would break up the monopolies and bring market discipline to bear to eliminate predatory pricing practices. When governments become the predators, however, the regulatory structure itself acts as one huge barrier to entry preventing competitors from entering the marketplace. A recent conference on insurance reform put on by the American Enterprise Institute illustrated how the balkanized system of insurance regulation throws up barriers to entry by international insurance companies who are not prepared to adjust their business models to accommodate 50 different systems of price controls and policy extortion. 14

In the face of premium price caps and other predatory actions by state governments and regulatory commissions, private insurers are turning increasingly to other insurance-policy requirements to pass the cost of the government regulatory mandates along to consumers and to bring their risk exposure into closer alignment with their premium income. For example, some insurers are more vigilantly inspecting homes before underwriting a home-owners policy and requiring policyholders to take certain precautionary actions to reduce the likelihood of certain types of losses.

In hurricane-prone areas in Eastern and Gulf states, such as Connecticut, some homeowner insurers began requiring homeowners to install storm-resistant window shutters to retain wind coverage. Connecticut promptly enacted a law baring insurers from requiring permanent shutters as a condition of insuring property in the state —and the vicious cycle continues.

Conclusion

When regulators act like predacious do gooders, consumers suffer.

Regulators who impose price controls and other coercive regulatory regimes have neither sound economic theory nor solid empirical basis on which to intervene in the marketplace. Rather, they simply presume what must be demonstrated to justify the social and economic dislocation they bring in their wake, namely that there exists a sound scientific case for why rate regulation, and particularly preemptive rate regulation, is economically justified either as a matter of principle, or as a means of providing consumers with better products and services.

The entire edifice of insurance premium regulation by state governments remains trapped in New Deal amber. There is no demonstrable justification for rate regulation nor is there even a measurable standard by which to determine if rate regulation historically has achieved even the goals set for it. Indeed, there is ample empirical evidence of just the opposite. 15

As one of the last remnants of unreconstructed intrusive pre-World War II government price fixing and excessive economic regulation, the bureaucratic apparatus that regulates the insurance industry in the United States today is in critical need of review, reform and modernization. One hopes that the revived interest in this issue will lead quickly to a systematic identification of needless rules and regulations that can be eliminated and in the process elucidate a range of market-based models that can provide the basis for more efficient regulation of the insurance industry in the 21 st century.

To the extent that insurance remains a heavily regulated industry, it will be all the more critical to examine alternative models of regulation that incorporate regulatory competition based on a Federalism model to provide a systemic check on regulatory over reach. Only such models can accommodate the three d istinguishing traits that characterize today’s global economy:

- Different forms of financial services compete one-on-one;

- There increasingly is tighter integration of markets for goods and services; and

- There is an ongoing revolution in telecommunications that affects all information-based products and services.

One option for reform that takes these three considerations into account would be an optional federal charter, which would allow insurance companies to choose between a state or federal regulator. Another Federalist approach to regulatory reform would be to consider a range of different interstate compact arrangements in which market-based reforms could be tested on a wide scale, with the goal, perhaps of encouraging model state legislation suitable for a 21 st century global market.

However insurance regulation is modernized, one conclusion is obvious: In today ’ s electronically networked, highly integrated global economy, regulatory provincialism has become not just an anachronism bu t also a dereliction of the best interests of the citizens of the several states.

Endnotes

- Pieler, George and Lawrence A. Hunter, Ph.D., Issue Brief, “Principles and Suggestions for the Review of Insurance Regulation,” Institute for Policy Innovati on, December 20, 2007.

- Pieler, George and Lawrence A. Hunter, Ph.D., Comments on, NAIC 8/28/07 Draft, “Personal Lines Regulatory Framework,” Institute for Policy Innovation, submitted September 27, 2007.

- Kanjorski, Paul, “The Need for Insurance Regulatory Reform,” Hearing before the Subcommittee on Capital Markets, Insurance, and Government Sponsored Enterprises of the House Committee on Financial Services, October 3, 2007.

- Pieler, George and Lawrence Hunter, “Avoiding a Stormy Future of State Insurance Regulation,” The Hill, September 25, 2007, and see also, http://www.policybytes.org/blog/PolicyBytes.nsf/dx/beware-of-politicians-spreading-the-risk.htm.

- http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Rent-seeking.

- Pieler, George and Lawrence Hu nter, “Great New Idea: Subprime Insurance,” Forbes Online, November 30, 2007, http://www.forbes.com/2007/11/30/sub-prime-insurance-oped-cx_gplh_1130subprime_print.html.

- See, for example, CEI Web Memo, “How an OFC Would Impact the States: A Response to Governors Sebalius and Perdue,” Eli Lehrer, Senior Fellow, Competitive Enterprise Institute, November 2, 2007 No. 1 ( http://www.cei.org/pdf/6238.pdf), and Think Ahead, “Treasury Prepares to Lay Down a Marker for the Future” (Part 1, October 29, 2007 a nd Part 2, November 26, 2007), Peter J. Wallison, American Enterprise Institute, ( http://www.aei.org/publications/pageID.607,msgKey.20040413154944744,filter.all/default.asp).

- See NAIC op cit. and the 8/28/07 response by Pieler and Hunter, op cit.

- See, for example, Henry Hazlitt, Economics in One Lesson: The Shortest and Surest Way to Understand Basic Economics, Chapter XVII, Three Rivers Press, New York, 1946.

- “Mugabe Warns Firms Against Halting Production,” July 6, 2007, http://news.bbc.co .uk/2/hi/africa/6283990.stm.

- Myers, Anika Palm “50,000 to lose State Farm insurance,” OrlandoSentinel.com, July 20, 2007, http://www.orlandosentinel.com/news/specials/orl-statefarm2007jul20,0,849873.story.

- The McCarran-Ferguson Act grants insurance companies immunity from prosecution under the federal antitrust laws.

- http://www.massbar.org/for-attorneys/publications/massachusetts-law-review/2006/v90-n2/regulatory-taking-claims-in-massachusetts-following-the-lingle-and-gove-descisions.

- “Will an Optional Federal Charter for Insurers Increase International Insurance Competition?” Conference held at the American Enterprise Institute, Thursday, December 20, 2007. Transcript available at: http://www.aei.o rg/events/filter.all,eventID.1622/transcript.asp.

- See for example, “Treating the Symptom Instead of the Disease: The Weak Case for Re-Capping Health Insurance Rates,” The Empire Center for New York State Policy, March 20, 2006.

About the Author

Lawrence A. Hunter is a senior research fellow at the Institute for Policy Innovation.